The Articulate Mammal (43 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

‘Repairs’ – situations when speakers correct themselves – are sometimes proposed as an extra source of information, as in:

FERDINAND CRASHED THE CAR ON MONDAY, SORRY, ON TUESDAY.

But in repairs there is a relatively long time-lag between making a mistake and correcting it (Blackmer and Mitton 1991). Mostly, speakers behave as if they are listening to another speaker: ‘Controlling one’s own speech is like attending to somebody else’s talk’ (Levelt 1983: 96–7). So repairs do not shed as much light as we might hope on the original planning process.

We therefore have to rely on indirect evidence. This is of two main types. First of all, we can look at the pauses in spontaneous speech. The object of this is to try to detect pause patterns – gaps in utterances – which may give clues about when speech is planned. Second, we can examine speech errors, both the slips of the tongue found in the conversation of normal people (e.g. HAP-SLAPPY for ‘slap-happy’, CANTANKEROUS for ‘contentious’), as well as the more severe disturbances of aphasics – people whose speech is impaired due to some type of brain damage (e.g. TARIB for ‘rabbit’, RABBIT for ‘apple’). Breakdown of the normal patterns may give us vital information about the way we plan and produce what we say, especially as: ‘Natural speech is full of mismatches between intention and output.’ (Harley 2006).

PAUSES

It may seem rather paradoxical to investigate speech by studying non-speech. But the idea is not as irrelevant as it appears at first sight. Around 40 to 50 per cent of an average spontaneous utterance consists of silence, although to hearers the proportion does not seem as high because they are too busy listening to what is being said.

The pauses in speech are of two main types:

breathing

pauses and

hesitation

pauses, sometimes with

er … um

vocalizations, known as

filled pauses

. The first type are relatively easy to cope with. There are relatively few of them, partly because we slow down our rate of breathing when we speak, and they account for only about 5 per cent of the gaps in speech. They tend to come at grammatical boundaries, although they do not necessarily do so (Henderson

et al.

1965).

Hesitation

pauses are more promising. There are more of them and they do not have any obvious physical purpose comparable to that of filling one’s lungs with air. Normally they account for one-third to one-half of the time taken up in talking. Speech in which such pausing does not occur is sometimes referred to as ‘inferior’ speech (Jackson 1932). Either it has been rehearsed beforehand, or the speaker is merely stringing together a number of standard phrases she habitually repeats, as when the mother of the 7-yearold who threw a stone through my window rattled off at top speed, ‘I do apologize, he’s never done anything like that before, I can’t think what came over him, he’s such a good quiet little boy usually, I’m quite flabbergasted.’ Unfortunately, we tend to over-value fluent, glib speakers who may not be thinking what they are saying, and often condemn a hesitant or stammering speaker who may be thinking very hard.

Hesitation pauses are rather difficult to measure, because a long-drawn-out word such as WE … ELL, IN FA … ACT may be substituted for a pause. This type of measurement problem may account for the huge differences of view found among psycholinguists who have done research on this topic. The basic argument is about

where

exactly the pauses occur. One researcher claims that hesitations occur mainly after the first word in the clause or sentoid (Boomer 1965). But other psycholinguists, whose experiments seem equally convincing, have found pauses mainly before important lexical items (Goldman-Eisler 1964; Butterworth 1980). It seems impossible, from just reading about their experiments, to judge who is right.

But in spite of this seemingly radical disagreement we can glean one important piece of information.

All

researchers agree that speakers do not normally pause between clauses, they pause

inside

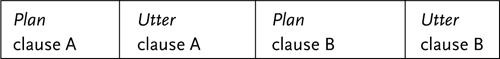

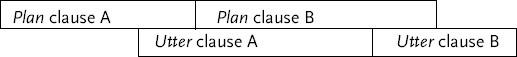

them. This means that there is overlapping in the planning and production of clauses. That is, instead of a simple sequence:

we must set up a more complicated model:

In other words, it is quite clear that we do not cope with speech one clause at a time. We begin to plan the next clause while still uttering the present one.

Armed with this vital piece of information, we can now attempt to elaborate the picture by looking at the evidence from speech errors.

SPEECH ERRORS: THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

Linguists are interested in speech errors because they hope that language in a broken-down state may be more revealing than language which is working perfectly. It is possible that speech is like an ordinary household electrical system, which is composed of several relatively independent circuits. We cannot discover very much about these circuits when all the lamps and sockets are working perfectly. But if a mouse gnaws through a cable in the kitchen and fuses one circuit, then we can immediately discover which lamps and sockets are linked together under normal working conditions. In the same way, it might be possible to find selective impairment of different aspects of speech.

The errors we shall be dealing with are, first, slips of the tongue and, second, the speech of aphasics – people with some more serious type of speech disturbance. Let us consider the nature of this evidence.

Everybody’s tongue slips now and again, most often when the tongue’s owner is tired, a bit drunk or rather nervous. So errors of this type are common enough to be called normal. However, if you mention the topic of slips of the tongue to a group of people at least one of them is likely to smirk knowingly and say ‘Ah yes, tongue slips are sexual in origin, aren’t they?’ This fairly popular misconception has arisen because Sigmund Freud, the great Viennese psychologist, wrote a paper suggesting that words sometimes slipped out from a person’s subconscious thoughts, which in his view were often concerned with sex. For example, he quotes the case of a woman who said her cottage was situated ON THE HILL-THIGH (BERGLENDE) instead of ‘on the hillside’ (Berglehne), after she had been trying to recall a childhood incident in which ‘part of her body had been grasped by a prying and lascivious hand’ (Freud 1901). In fact, this type of example occurs only in a relatively small number of tongue slips (Ellis 1980). It is true, possibly, that a percentage of girls have the embarrassing experience of sinking rapturously into, say, Archibald’s arms while inadvertently murmuring ‘Darling Algernon’. It is also perhaps true that anyone talking about a sexlinked subject may get embarrassed and stumble over his words, like the anthropology professor, who, red to the ears with confusion, talked about a PLENIS-BEEDING CEREMONY (penis-bleeding ceremony) in Papua New Guinea. But otherwise there seems little to support the sexual origin myth. Perhaps one might add that people tend to notice and remember sexual slips more than any other type. During the anthropology lecture mentioned above, almost everybody heard and memorized the PLENIS-BEEDING example. But few people afterwards, when questioned, had heard the lecturer say, YAM’S BOOK ON YOUNG-GROWING (Young’s book on yam-growing). So laying aside the sex myth, we may say that slips of the tongue tell us more

about the way a person plans and produces speech than about his or her sexual fantasies.

Aphasia is rather different from slips of the tongue, in that it is far from ‘normal’. The name

aphasia

comes from a Greek word which means literally ‘without speech’, though is widely used in both the UK and USA to mean ‘impaired speech’ (the more accurate term

dysphasia

is now rarely found).

Aphasia covers an enormous range of speech problems. At one end of the range we find people who can only say a single word such as O DEAR, O DEAR, O DEAR, or more usually, a swear word such as DAMN, DAMN, DAMN. One unproved theory is that people who have had a severe stroke sometimes find their speech ‘petrified’ into the word they were uttering as the stroke occurred. At the other end of the scale are people with only occasional wordfinding difficulties – it is not always clear where true aphasia ends and normal slips of the tongue begin. The fact that one merges into the other means that we can examine both types of error together in our search for clues about the planning and production of speech.

The typology of aphasia (attempts to classify aphasia into different kinds of disturbance) is a confused and controversial topic, and is beyond the scope of this book. Here we shall look at examples of name-finding difficulties, which is perhaps the most widespread of all aphasic symptoms. It affects some patients more than others, but it is usually present to some degree in most types of speech disturbance. A vivid description of this problem occurs in Kingsley Amis’s novel

Ending Up

(1974). The fictional aphasic is a retired university teacher, Professor George Zeyer, who had a stroke 5 months previously:

‘Well, anyway, to start with he must have a, a, thing, you know, you go about in it, it’s got, er, they turn round. A very expensive one, you can be sure. You drive it, or someone else does in his case. Probably gold, gold on the outside. Like that other chap. A bar – no. And probably a gold, er, going to sleep on it. And the same in his … When he washes himself. If he ever does, of course. And eating off a gold – eating off it, you know. Not to speak of a private, um, uses it whenever he wants to go anywhere special, to one of those other places down there to see his pals. Engine. No. With a fellow to fly it for him. A plate. No, but you know what I mean. And the point is it’s all because of us. Without us he’d be nothing, would he? But for us he’d still be living in his, ooh, made out of … with a black woman bringing him, off the – growing there, you know. And the swine’s supposed to be some sort of hero. Father of his people and all that. A plane, a private plane, that’s it.’

It was not that George was out of his mind, merely that his stroke had afflicted him, not only with hemiplegia, but also with that condition in which the sufferer finds it difficult to remember nouns, common terms, the names of familiar objects. George was otherwise fluent and accurate and responded normally to other’s speech. His fluency was especially notable; he was very good at not pausing at moments when a sympathetic hearer could have supplied the elusive word. Doctors, including Dr Mainwaring, had stated that the defect might clear up altogether in time, or might stay as it was, and that there was nothing to be done about it.

Of course, not every aphasic is as fluent as George. And sometimes a patient is in the disquieting situation of thinking she has found the right word – only to discover to her dismay, when she utters it, that it is the wrong one. A description of this unnerving experience occurs in Nabokov’s

Pale Fire

:

She still could speak. She paused and groped and found

What seemed at first a serviceable sound,

But from adjacent cells imposters took

The place of words she needed, and her look

Spelt imploration as she sought in vain

To reason with the monsters in her brain.

Perhaps the following two extracts will give a clearer picture of the problem. They are taken from tape-recordings of a severely aphasic patient in her seventies who had had a stroke 2 months earlier.

The patient (P) has been uttering the word RHUBARB, apparently because she is worried about her garden which is going to rack and ruin while she is in hospital. The therapist (T) tries to comfort her then says:

| T: | NOW THEN, WHAT’S THIS A PICTURE OF? (showing a picture of an apple) |

| P: | RA-RA-RABBIT. |

| T: | NO, NOT A RABBIT. IT’S A KIND OF FRUIT. |

| P: | FRUIT. |

| T: | WHAT KIND OF FRUIT IS IT? |

| P: | O THIS IS A LOVELY RABBIT. |

| T: | NOT A RABBIT, NO. IT’S AN APPLE. |

| P: | APPLE, YES. |

| T: | CAN YOU NAME ANY OTHER PIECES OF FRUIT? WHAT OTHER KINDS OF FRUIT WOULD YOU HAVE IN A DISH WITH AN APPLE? |

| P: | BEGINNING WITH AN A? |

| T: | NO, NOT NECESSARILY. |

| P: | O WELL, RHUBARB. |

| T: | PERHAPS, YES. |

| P: | OR RHUBARB. |