The Ascent of Man (2 page)

Authors: Jacob Bronowski

In rendering the text used on the screen, I have followed the spoken word closely, for two reasons. First, I wanted to preserve the spontaneity of thought in speech, which I had done all I could to foster wherever I went. (For the same reason, I had chosen whenever possible to go to places that were as fresh to me as to the viewer.) Second and

more important, I wanted equally to guard the spontaneity of the argument. A spoken argument is informal and heuristic; it singles out the heart of the matter and shows in what way it is crucial and new; and it gives the direction and line of the solution so that, simplified as it is, still the logic is right. For me, this philosophic form of argument is the foundation of science, and nothing should

be allowed to obscure it.

The content of these essays is in fact wider than the field of science, and I should not have called them

The Ascent of Man

had I not had in mind other steps in our cultural evolution too. My ambition here has been the same as in my other books, whether in literature or in science: to create a philosophy for the twentieth century which shall be all of one piece. Like

them, this series presents a philosophy rather than a history, and a philosophy of nature rather than of science. Its subject is a contemporary version of what used to be called Natural Philosophy. In my view, we are in a better frame of mind today to conceive a natural philosophy than at any time in the last three hundred years. This is because the recent findings in human biology have given a new

direction to scientific thought, a shift from the general to the individual, for the first time since the Renaissance opened the door into the natural world.

There cannot be a philosophy, there cannot even be a decent science, without humanity. I hope that sense of affirmation is manifest in this book. For me, the understanding of nature has as its goal the understanding of human nature, and

of the human condition within nature.

To present a view of nature on the scale of this series is as much an experiment as an adventure, and I am grateful to those who made both possible. My first debt is to the Salk Institute for Biological Studies which has long supported my work on the subject of human specificity, and which gave me a year of sabbatical leave to film the programmes. I am greatly

indebted also to the British Broadcasting Corporation and its associates, and very particularly there to Aubrey Singer who invented the massive theme and urged it on me for two years before I was persuaded.

The list of those who helped to make the programmes is so long that I must put it on a page of its own, and thank them in a body; it was a pleasure to work with them. However, I cannot pass

over the names of the producers that stand at the head of the list, and particularly Adrian Malone and Dick Gilling, whose imaginative ideas transubstantiated the word into flesh and blood.

Two people worked with me on this book, Josephine Gladstone and Sylvia Fitzgerald, and did much more; I am happy to be able to thank them here for their long task. Josephine Gladstone had charge of all the

research for the series since 1969, and Sylvia Fitzgerald helped me plan and prepare the script at each successive stage. I could not have had more stimulating colleagues.

J. B.

La Jolla, California

August 1973

LOWER THAN THE ANGELS

Man is a singular creature. He has a set of gifts which make him unique among the animals: so that, unlike them, he is not a figure in the landscape – he is a shaper of the landscape. In body and in mind he is the explorer of nature, the ubiquitous animal, who did not find but has made his home in every continent.

It is reported that when the Spaniards arrived

overland at the Pacific Ocean in 1769 the California Indians used to say that at full moon the fish came and danced on these beaches. And it is true that there is a local variety of fish, the grunion, that comes up out of the water and lays its eggs above the normal high-tide mark. The females bury themselves tail first in the sand and the males gyrate round them and fertilise the eggs as they are

being laid. The full moon is important, because it gives the time needed for the eggs to incubate undisturbed in the sand, nine or ten days, between these very high tides and the next ones that will wash the hatched fish out to sea again.

Every landscape in the world is full of these exact and beautiful adaptations, by which an animal fits into its environment like one cog-wheel into another.

The sleeping hedgehog waits for the spring to burst its metabolism into life. The humming-bird beats the air and dips its needle-fine beak into hanging blossoms. Butterflies mimic leaves and even noxious creatures to deceive their predators. The mole plods through the ground as if he had been designed as a mechanical shuttle.

So millions of years of evolution have shaped the grunion to fit and

sit exactly with the tides. But nature – that is, biological evolution – has not fitted man to any specific environment. On the contrary, by comparison with the grunion he has a rather crude survival kit; and yet – this is the paradox of the human condition – one that fits him to all environments. Among the multitude of animals which scamper, fly, burrow and swim around us, man is the only one who

is not locked into his environment. His imagination, his reason, his emotional subtlety and toughness, make it possible for him not to accept the environment but to change it. And that series of inventions, by which man from age to age has remade his environment, is a different kind of evolution – not biological, but cultural evolution. I call that brilliant sequence of cultural peaks

The Ascent

of Man

.

I use the word ascent with a precise meaning. Man is distinguished from other animals by his imaginative gifts. He makes plans, inventions, new discoveries, by putting different talents together; and his discoveries become more subtle and penetrating, as he learns to combine his talents in more complex and intimate ways. So the great discoveries of different ages and different cultures,

in technique, in science, in the arts, express in their progression a richer and more intricate conjunction of human faculties, an ascending trellis of his gifts.

Of course, it is tempting – very tempting to a scientist – to hope that the most original achievements of the mind are also the most recent. And we do indeed have cause to be proud of some modern work. Think of the unravelling of the

code of heredity in the DNA spiral; or the work going forward on the special faculties of the human brain. Think of the philosophic insight that saw into the Theory of Relativity or the minute behaviour of matter on the atomic scale.

Yet to admire only our own successes, as if they had no past (and were sure of the future), would make a caricature of knowledge. For human achievement, and science

in particular, is not a museum of finished constructions. It is a progress, in which the first experiments of the alchemists also have a formative place, and the sophisticated arithmetic that the Mayan astronomers of Central America invented for themselves independently of the Old World. The stonework of Machu Picchu in the Andes and the geometry of the Alhambra in Moorish Spain seem to us, five

centuries later, exquisite works of decorative art. But if we stop our appreciation there, we miss the originality of the two cultures that made them. Within their time, they are constructions as arresting and important for their peoples as the architecture of DNA for us.

In every age there is a turning-point, a new way of seeing and asserting the coherence of the world. It is frozen in the statues

of Easter Island that put a stop to time – and in the medieval clocks in Europe that once also seemed to say the last word about the heavens for ever. Each culture tries to fix its visionary moment, when it was transformed by a new conception either of nature or of man. But in retrospect, what commands our attention as much are the continuities – the thoughts that run or recur from one civilisation

to another. There is nothing in modern chemistry more unexpected than putting together alloys with new properties; that was discovered after the time of the birth of Christ in South America, and long before that in Asia. Splitting and fusing the atom both derive, conceptually, from a discovery made in prehistory: that stone and all matter has a structure along which it can be split and put

together in new arrangements. And man made biological inventions almost as early: agriculture – the domestication of wild wheat, for example – and the improbable idea of taming and then riding the horse.

In following the turning-points and the continuities of culture, I shall follow a general but not a strict chronological order, because what interests me is the history of man’s mind as an unfolding

of his different talents. I shall be relating his ideas, and particularly his scientific ideas, to their origins in the gifts with which nature has endowed man, and which make him unique. What I present, what has fascinated me for many years, is the way in which man’s ideas express what is essentially human in his nature.

So these programmes or essays are a journey through intellectual history,

a personal journey to the high points of man’s achievement. Man ascends by discovering the fullness of his own gifts (his talents or faculties) and what he creates on the way are monuments to the stages in his understanding of nature and of self – what the poet W. B. Yeats called ‘monuments of unageing intellect’.

Where should one begin? With the Creation – with the creation of man himself. Charles

Darwin pointed the way with

The Origin of Species

in 1859, and then in his book of 1871,

The Descent of Man

. It is almost certain now that man first evolved in Africa near the equator. Typical of the places where his evolution may have begun is the savannah country that stretches out across Northern Kenya and South West Ethiopia near Lake Rudolf. The lake lies in a long ribbon north and south

along the Great Rift Valley, hemmed in by over four million years of thick sediments that settled in the basin of what was formerly a much more extensive lake. Much of its water comes by way of the winding, sluggish Omo. For the origins of man, this is a possible area: the valley of the river Omo in Ethiopia near Lake Rudolf.

The ancient stories used to put the creation of man into a golden age

and a beautiful, legendary landscape. If I were telling the story of Genesis now, I should be standing in the Garden of Eden. But this is manifestly not the Garden of Eden. And yet I am at the navel of the world, at the birthplace of man, here in the East African Rift Valley, near the equator. The slumped levels in the Omo basin, the bluffs, the barren delta, record a historic past of man. And

if this ever was a Garden of Eden, why, it withered millions of years ago.

I have chosen this place because it has a unique structure. In this valley was laid down, over the last four million years, layer upon layer of volcanic ash, interbedded with broad bands of shale and mudstone. The deep deposit was formed at different times, one stratum after another, visibly separated according to age:

four million years ago, three million years ago, over two million years ago, somewhat under two million years ago. And then the Rift Valley buckled it and stood it on end, so that now it makes a map in time, which we see stretching into the distance and the past. The record of time in the strata, which is usually buried underfoot, has been tip-tilted in the cliffs that flank the Omo, and spread out

like the ribs of a fan.

These cliffs are the strata on edge: in the foreground the bottom level, four million years old, and beyond that the next lowest, well over three million years old. The remains of a creature like man appear beyond that, and the remains of the animals that lived at the same time.

The animals are a surprise, because it turns out that they have changed so little. When we

find in the sludge of two million years ago the fossils of the creature who was to become man, we are struck by the differences between his skeleton and ours – by the development of the skull, for instance. So, naturally, we expect the animals of the savannah also to have changed greatly. But the fossil record in Africa shows that this is not so. Look as the hunter does at the Topi antelope now.

The ancestor of man that hunted its ancestor two million years ago would at once recognise the Topi today. But he would not recognise the hunter today, black or white, as his own descendant.

The animals are a surprise, because it turns out that they have changed so little.

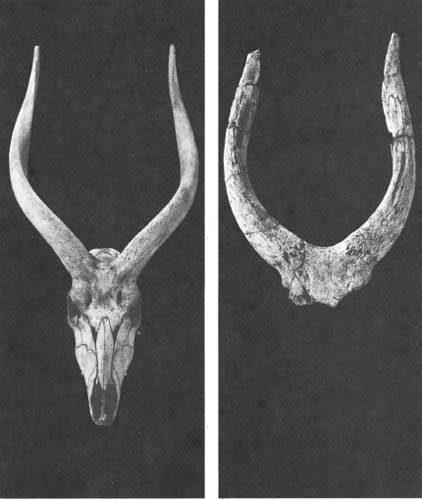

The animals are a surprise, because it turns out that they have changed so little.Modern and fossil nyala horns from Omo. The fossil horns are over two million years old

.

Yet it is not hunting in itself (or any other single pursuit) that has changed man. For we find that among the animals the hunter has changed as little as the hunted. The serval cat is still powerful in pursuit, and the oryx

is still swift in flight; both perpetuate the same relation between their species as they did long ago. Human evolution began when the African climate changed to drought: the lakes shrank, the forest thinned out to savannah. And evidently it was fortunate for the forerunner of man that he was not well adapted to these conditions. For the environment exacts a price for the survival of the fittest;

it captures them. When animals like Grevy’s zebra were adapted to the dry savannah, it became a trap in time as well as space; they stayed where they were, and much as they were. The most gracefully adapted of all these animals is surely Grant’s gazelle; yet its lovely leap never took it out of the savannah.