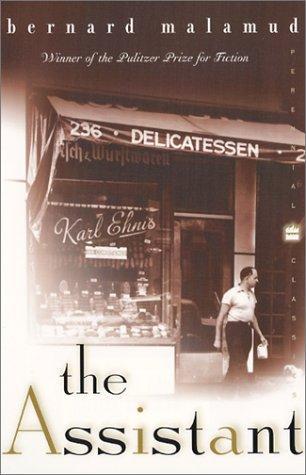

The assistant

Authors: Bernard Malamud

Tags: #Fiction, #Fiction - General, #General, #Literary, #Classic fiction, #Psychological fiction, #N.Y.), #Italian American men, #Brooklyn (New York

Bernard Malamud The Assistant

First published in 1957

1

The early November street was dark though night had ended, but the wind, to the grocer's surprise, already clawed. It flung his apron into his face as he bent for the two milk cases at the curb. Morris Bober dragged the heavy boxes to the door, panting. A large brown bag of hard rolls stood in the doorway along with the sour-faced, gray-haired Poilisheh huddled there, who wanted one. "What's the matter so late?" "Ten after six," said the grocer. "Is cold," she complained. Turning the key in the lock he let her in. Usually he lugged in the milk and lit the gas radiators, but the Polish woman was impatient. Morris poured the bag of rolls into a wire basket on the counter and found an unseeded one for her. Slicing it in halves, he wrapped it in white store paper. She tucked the roll into her cord market bag and left three pennies on the counter. He rang up the sale on an old noisy cash register, smoothed and put away the bag the rolls had come in, finished pulling in the milk, and stored the bottles at the bottom of the refrigerator. He lit the gas radiator at the front of the store and went into the back to light the one there. He boiled up coffee in a blackened enamel pot and sipped it, chewing on a roll, not tasting what he was eating. After he had cleaned up he waited; he waited for Nick Fuso, the upstairs tenant, a young mechanic who worked in a garage in the neighborhood. Nick came in every morning around seven for twenty cents' worth of ham and a loaf of bread. But the front door opened and a girl of ten entered, her face pinched and eyes excited. His heart held no welcome for her. "My mother says," she said quickly, "can you trust her till tomorrow for a pound of butter, loaf of rye bread and a small bottle of cider vinegar?" He knew the mother. "No more trust." The girl burst into tears. Morris gave her a quarter-pound of butter, the bread and vinegar. He found a penciled spot on the worn counter, near the cash register, and wrote a sum under "Drunk Woman." The total now came to $2.03, which he never hoped to see. But Ida would nag if she noticed a new figure, so he reduced the amount to $1.61. His peace-the little he lived with-was worth forty-two cents. He sat in a chair at the round wooden table in the rear of the store and scanned, with raised brows, yesterday's Jewish paper that he had already thoroughly read. From time to time he looked absently through the square windowless window cut through the wall, to see if anybody had by chance come into the store. Sometimes when he looked up from his newspaper, he was startled to see a customer standing silently at the counter. Now the store looked like a long dark tunnel. The grocer sighed and waited. Waiting he thought he did poorly. When times were bad time was bad. It died as he waited, stinking in his nose. A workman came in for a fifteen-cent can of King Oscar Norwegian sardines. Morris went back to waiting. In twenty-one years the store had changed little. Twice he had painted all over, once added new shelving. The old-fashioned double windows at the front a carpenter had made into a large single one. Ten years ago the sign hanging outside fell to the ground but he had never replaced it. Once, when business hit a long good spell, he had had the wooden icebox ripped out and a new white refrigerated showcase put in. The showcase stood at the front in line with the old counter and he often leaned against it as he stared out of the window. Otherwise the store was the same. Years ago it was more a delicatessen; now, though he still sold a little delicatessen, it was more a poor grocery. A half-hour passed. When Nick Fuso failed to appear, Morris got up and stationed himself at the front window, behind a large cardboard display sign the beer people had rigged up in an otherwise empty window. After a while the hall door opened, and Nick came out in a thick, hand-knitted green sweater. He trotted around the corner and soon returned carrying a bag of groceries. Morris was now visible at the window. Nick saw the look on his face but didn't look long. He ran into the house, trying to make it seem it was the wind that was chasing him. The door slammed behind him, a loud door. The grocer gazed into the street. He wished fleetingly that he could once more be out in the open, as when he was a boy -never in the house, but the sound of the blustery wind frightened him. He thought again of selling the store but who would buy? Ida still hoped to sell. Every day she hoped. The thought caused him grimly to smile, although he did not feel like smiling. It was an impossible idea so he tried to put it out of his mind. Still, there were times when he went into the back, poured himself a spout of coffee and pleasantly thought of selling. Yet if he miraculously did, where would he go, where? He had a moment of uneasiness as he pictured himself without a roof over his head. There he stood in all kinds of weather, drenched in rain, and the snow froze on his head. No, not for an age had he lived a whole day in the open. As a boy, always running in the muddy, rutted streets of the village, or across the fields, or bathing with the other boys in the river; but as a man, in America, he rarely saw the sky. In the early days when he drove a horse and wagon, yes, but not since his first store. In a store you were entombed. The milkman drove up to the door in his truck and hurried in, a bull, for his empties. He lugged out a easeful and returned with two half-pints of light cream. Then Otto Vogel, the meat provisions man, entered, a bushy-mustached German carrying a smoked liverwurst and string of wieners in his oily meat basket. Morris paid cash for the liverwurst; from a German he wanted no favors. Otto left with the wieners. The bread driver, new on the route, exchanged three fresh loaves for three stale and walked out without a word. Leo, the cake man, glanced hastily at the package cake on top of the refrigerator and called, "See you Monday, Morris." Morris didn't answer. Leo hesitated. "Bad all over, Morris." "Here is the worst." "See you Monday." A young housewife from close by bought sixty-three cents' worth; another came in for forty-one cents'. He had earned his first cash dollar for the day. Breitbart, the bulb peddler, laid down his two enormous cartons of light bulbs and diffidently entered the back. "Go in," Morris urged. He boiled up some tea and served it in a thick glass, with a slice of lemon. The peddler eased himself into a chair, derby hat and coat on, and gulped the hot tea, his Adam's apple bobbing. "So how goes now?" asked the grocer. "Slow," shrugged Breitbart. Morris sighed. "How is your boy?" Breitbart nodded absently, then picked up the Jewish paper and read. After ten minutes he got up, scratched all over, lifted across his thin shoulders the two large cartons tied together with clothesline and left. Morris watched him go. The world suffers. He felt every schmerz. At lunchtime Ida came down. She had cleaned the whole house. Morris was standing before the faded couch, looking out of the rear window at the back yards. He had been thinking of Ephraim. His wife saw his wet eyes. "So stop sometime, please." Her own grew wet. He went to the sink, caught cold water in his cupped palms and dipped his face into it. "The Italyener," he said, drying himself, "bought this morning across the street." She was irritated. "Give him for twenty-nine dollars five rooms so he should spit in your face." "A cold water flat," he reminded her. "You put in gas radiators." "Who says he spits? This I didn't say." "You said something to him not nice?" "Me?" "Then why he went across the street?" "Why? Go ask him," he said angrily. "How much you took in till now?" "Dirt." She turned away. He absent-mindedly scratched a match and lit a cigarette. "Stop with the smoking," she nagged. He took a quick drag, clipped the butt with his thumb nail and quickly thrust it under his apron into his pants pocket. The smoke made him cough. He coughed harshly, his face lit like a tomato. Ida held her hands over her ears. Finally he brought up a gob of phlegm and wiped his mouth with his handkerchief, then his eyes. "Cigarettes," she said bitterly. "Why don't you listen what the doctor tells you?" "Doctors," he remarked. Afterward he noticed the dress she was wearing. "What is the picnic?" Ida said, embarrassed, "I thought to myself maybe will come today the buyer." She was fifty-one, nine years younger than he, her thick hair still almost all black. But her face was lined, and her legs hurt when she stood too long on them, although she now wore shoes with arch supports. She had waked that morning resenting the grocer for having dragged her, so many years ago, out of a Jewish neighborhood into this. She missed to this day their old friends and landsleit-lost for parnusseh unrealized. That was bad enough, but on top of their isolation, the endless worry about money embittered her. She shared unwillingly the grocer's fate though she did not show it and her dissatisfaction went no farther than nagging-her guilt that she had talked him into a grocery store when he was in the first year of evening high school, preparing, he had said, for pharmacy. He was, through the years, a hard man to move. In the past she could sometimes resist him, but the weight of his endurance was too much for her now. "A buyer," Morris grunted, "will come next Purim." "Don't be so smart. Karp telephoned him." "Karp," he said in disgust. "Where he telephoned-the cheapskate?" "Here." "When?" "Yesterday. You were sleeping." "What did he told him?" "For sale a store-yours, cheap." "What do you mean cheap?" "The key is worth now nothing. For the stock and the fixtures that they are worth also nothing, maybe three thousand, maybe less." "I paid four." "Twenty-one years ago," she said irritably. "So don't sell, go in auction." "He wants the house too?" "Karp don't know. Maybe." "Big mouth. Imagine a man that they held him up four times in the last three years and he still don't take in a telephone. What he says ain't worth a cent. He promised me he wouldn't put in a grocery around the corner, but what did he put?-a grocery. Why does he bring me buyers? Why didn't he keep out the German around the corner?" She sighed. "He tries to help you now because he feels sorry for you." "Who needs his sorrow?" Morris said. "Who needs him?" "So why you didn't have the sense to make out of your grocery a wine and liquor store when came out the licenses?" "Who had cash for stock?" "So if you don't have, don't talk." "A business for drunken bums." "A business is a business. What Julius Karp takes in next door in a day we don't take in in two weeks." But Ida saw he was annoyed and changed the subject. "I told you to oil the floor." "I forgot." "I asked you special. By now would be dry." "I will do later." "Later the customers will walk in the oil and make everything dirty." "What customers?" he shouted. "Who customers? Who comes in here?" "Go," she said quietly. "Go upstairs and sleep. I will oil myself." But he got out the oil can and mop and oiled the floor until the wood shone darkly. No one had come in. She had prepared his soup. "Helen left this morning without breakfast." "She wasn't hungry." "Something worries her." He said with sarcasm, "What worries her?" Meaning: the store, his health, that most of her meager wages went to keep up payments on the house; that she had wanted a college education but had got instead a job she disliked. Her father's daughter, no wonder she didn't feel like eating. "If she will only get married," Ida murmured. "She will get." "Soon." She was on the verge of tears. He grunted. "I don't understand why she don't see Nat Pearl anymore. All summer they went together like lovers." "A show off." "He'll be someday a rich lawyer." "I don't like him." "Louis Karp also likes her. I wish she will give him a chance." "A stupe," Morris said, "like the father." "Everybody is a stupe but not Morris Bober." He was staring out at the back yards. "Eat already and go to sleep," she said impatiently. He finished the soup and went upstairs. The going up was easier than coming down. In the bedroom, sighing, he drew down the black window shades. He was half asleep, so pleasant was the anticipation. Sleep was his one true refreshment; it excited him to go to sleep. Morris took off his apron, tie and trousers, and laid them on a chair. Sitting at the edge of the sagging wide bed, he unlaced his misshapen shoes and slid under the cold covers in shirt, long underwear and white socks. He nudged his eye into the pillow and waited to grow warm. He crawled toward sleep. But upstairs Tessie Fuso was running the vacuum cleaner, and though the grocer tried to blot the incident out of his mind, he remembered Nick's visit to the German and on the verge of sleep felt bad. He recalled the bad times he had lived through, but now times were worse than in the past; now they were impossible. His store was always a marginal one, up today, down tomorrow-as the wind blew. Overnight business could go down enough to hurt; yet as a rule it slowly recovered- sometimes it seemed to take forever-went up, not high enough to be really up, only not down. When he had first bought the grocery it was all right for the neighborhood; it had got worse as the neighborhood had. Yet even a year ago, staying open seven days a week, sixteen hours a day, he could still eke out a living. What kind of living?-a living; you lived. Now, though he toiled the same hard hours, he was close to bankruptcy, his patience torn. In the past when bad times came he had somehow lived through them, and when good times returned, they more or less returned to him. But now, since the appearance of H. Schmitz across the street ten months ago, all times were bad. Last year a broken tailor, a poor man with a sick wife, had locked up his shop and gone away, and from the minute of the store's emptiness Morris had felt a gnawing anxiety. He went with hesitation to Karp, who owned the building, and asked him to please keep out another grocery. In this kind of neighborhood one was more than enough. If another squeezed in they would both starve. Karp answered that the neighborhood was better than Morris gave it credit (for schnapps, thought the grocer), but he promised he would look for another tailor or maybe a shoemaker, to rent to. He said so but the grocer didn't believe him. Yet weeks went by and the store stayed empty. Though Ida pooh-poohed his worries, Morris could not overcome his underlying dread. Then one day, as he daily expected, there appeared a sign in the empty store window, announcing the coming of a new fancy delicatessen and grocery. Morris ran to Karp. "What did you do to me?" The liquor dealer said with a one-shouldered shrug, "You saw how long stayed empty the store. Who will pay my taxes? But don't worry," he added, "he'll sell more delicatessen but you'll sell more groceries. Wait, you'll