The Audrey of the Outback Collection (14 page)

Read The Audrey of the Outback Collection Online

Authors: Christine Harris

Audrey expected Mrs Paterson to tip the slopped tea from the saucer back into the cup, as Dad did. But the old lady pretended it wasn’t there. She added one sugar, a dash of milk, and stirred the tea in a clockwise direction six times. Then she took a sip and coughed.

‘It’s not too strong, is it?’ asked Audrey.

Mrs Paterson’s eyes watered. ‘Just a tickle in my throat. It’s delicious. Thank you.’

‘You have soft hands,’ said Audrey. ‘And none of your fingers are bent.’

Mrs Paterson made a strange noise in the back of her throat. ‘Thank you. I am most fortunate in that regard. I use hand cream. And there is lanoline in the wool I knit. Another good reason to keep one’s hands occupied in that way.’

‘Can we …

may

Dougie and I go to the Jenkins’s now, please?’ Audrey was afraid the old lady would change her mind. There was a town waiting outside the garden fence, other children to play with and a secret plan to carry out.

‘You may go,’ Mrs Paterson said at last. ‘I would accompany you, but my arthritis is not good today. Do you know the way?’

‘Yes, town is easy because the roads are straight.’

‘Be back by half-past five. Keep in mind that I cannot abide anyone who is not punctual.’

‘I won’t punch anyone. Neither will Dougie. He doesn’t like fighting.’

Mrs Paterson closed her eyes for a moment, then said, ‘

Punctual

. Not

punch you all

. I refer to you not being late.’

‘I can do that too,’ said Audrey.

The old lady narrowed her eyes. ‘You are being very polite today.’

‘That’s because I’m your project,’ said Audrey. ‘And

you’re

mine. I’m looking for your good side.’

Twenty

Audrey left the house with Mrs Paterson’s list of ‘Don’ts’ for walking through town ringing in her ears. It was almost as long as the list for how to behave inside the house. Mrs Paterson had finished with, ‘Don’t let the Jenkins children lead you into trouble.’ She had not said what kind of ‘trouble’. Audrey wished she had. That might have made the list more interesting. But Mrs Paterson had rules without many ideas.

If Audrey’s secret plan backfired, she knew she would get into trouble for sure.

Douglas gripped her hand firmly. His skipping tugged on her arm.

A large whirlwind sped across the road, gathering dust as Stumpy arrived.

Audrey grinned. ‘You were a long time.’ She understood his wanting to be with other camels because she was excited about making new friends too.

Clouds covered the sun. Audrey shivered, despite her cardigan. A breeze played with the hem of her blue smock-dress. Fine rain began to tickle her face.

Beltana was rich with water. Two creeks snaked around the town. Audrey wished her family had even

one

creek near their house. But at least they had the well and, so far, it had never dried up.

A boy with flappy ears walked past. He coughed with his mouth wide open. Mrs Paterson wouldn’t have liked that. You were supposed to cover your mouth when you coughed, so people couldn’t see down your throat.

‘Hello.’ Audrey smiled at the boy.

‘Hello,’ repeated Douglas.

The boy didn’t answer.

Douglas made a noise.

Stumpy whispered to Audrey.

‘No, Stumpy,’ Audrey replied. ‘There’s nothing wrong with Dougie. He’s just humming.’

Douglas hummed louder.

Audrey’s steps slowed as they walked past the hospital. She looked at each window, hoping to see a familiar face or a hand waving a handkerchief. But there was nothing. Not the slightest brush of a curtain.

There were more people in town than out bush. But more people didn’t always stop you feeling lonely.

Mrs Jenkins came bustling out of the house.

Twenty-one

They passed the tiny school with its pointed roof. It was surrounded by a wire fence with wooden posts. That wouldn’t keep the children in. They could squeeze through the gaps or climb over it. At home, Audrey and Price often thought of ways to avoid lessons with Mum at the kitchen table.

Audrey and Douglas reached the Jenkins’s house without breaking a single Mrs Paterson-rule. Although Stumpy had come along, and Mrs Paterson wouldn’t have liked that too much.

The Jenkins’s house was nestled between two others. Audrey could have guessed which one it was by the sound of all the children’s voices. They were raised in friendly argument. At least, she

hoped

it was friendly.

A line of scrappy bushes with more twigs than leaves divided the front and back yards. The fence was half-broken. The Jenkins’s house looked small for twelve people. It was made from flattened kerosene tins, the metal sheets dented here and there. Smoke rose from the chimney. The chimney looked like the most solid part of the building.

Stumpy hung back.

‘You can go and play if you want, Stumpy,’ said Audrey.

He was gone in a flash.

Audrey wasn’t sure about going in either. Ten was a lot of children to meet all at once. But Douglas dragged on her arm, pulling her forward. He couldn’t count to ten yet, so he wasn’t nervous.

As they neared the back of the house, there was a yell.

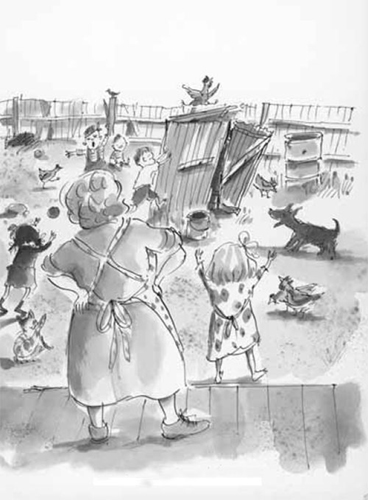

Her heart beating fast, Audrey rounded the corner. Children of varying heights stood in the backyard watching Boy. They bellowed a mixture of cheers and protests. Boy had both hands against the outside dunny and he was pushing hard. The dunny rocked back and forth. Muffled shouts came from inside.

Mrs Jenkins came bustling out of the house. ‘Boy. Stop that. If you had a brain it’d be lonely.’

‘Ma, he’s been in there that long his head’s caved in.’ Then Boy looked up, saw Audrey and grinned.

Mrs Jenkins turned. ‘I’m sorry … Boy isn’t usually …’ She wiped her hands on her dark green apron and shrugged. ‘Actually he

is

usually up to something. But I don’t always catch him at it.’

Boy started to introduce his brothers and sisters. Audrey wasn’t sure she would remember so many names. They all had crooked haircuts. There wasn’t a straight line on any head in the yard. The three girls wore overalls, like the boys.

‘I can do this … look.’ A short girl, about five years old, stretched her mouth to show that she had a tooth missing. Then she poked the tip of her tongue through the gap.

‘Dougie do this.’ He poked his right forefinger into his ear.

Thumping came from inside the dunny. The Jenkins mob ignored it.

Boy’s shirt was ripped and his grey shorts grubby. His legs were thin, with knobbly knees. Audrey was reminded of the goats back home. There was a dirty streak across Boy’s left cheek.

‘This is me brother, Simon, number four. Parker, number three.’ Boy rattled off the names and birth orders of each child. ‘Phillip doesn’t like being called number two.’ Boy’s eyes gleamed with mischief.

More thumping from inside the dunny interrupted the list of names. Boy undid the outside latch.

A lad who was slightly older and a lot redder in the face than Boy, flew out, his hands curled into fists. ‘Put up yer dooks.’

Boy shook his head. ‘We got visitors.’

The red-faced boy looked at Audrey and Douglas. ‘Are you the orphans?’

Audrey felt as though she had been slapped. ‘I am

not

an orphan. Neither is Dougie. Our mum’s in the hospital.’ But the word

orphan

made her think, for an instant, what it would feel like if Mum didn’t come home.

‘Liam, isn’t there a pile of wood waiting to be chopped?’ said Mrs Jenkins. ‘You just volunteered.’

‘But, Ma, it isn’t my turn …’

Mrs Jenkins raised one arm and pointed to the side of the house. She didn’t need to say anything else. Her arm said it all. ‘Settle down, the lot of you.’

Boy came to stand beside Audrey. ‘Ma made scones, and there’s real butter. From acow.’

Audrey realised she was hungry. She had never tasted cow butter, only goat butter, which was stinky. Mrs Paterson used dripping. She said bread and dripping had been good enough for her when she was growing up, so it was good enough for her visitors. It tasted all right. But real butter would be a treat.

Boy smiled at Audrey, his eyes switching from yellow to brown.

Audrey smiled back. Boy was cheeky, but not wicked. And he was daring, but not stupid—unless you counted rocking the dunny when your big brother was inside it. Boy was exactly the kind of friend she needed for her secret plan.

Twenty-two

Boy and Audrey sat on the Jenkins’s narrow back porch. Busy eating scones, they watched a rain shower sweep the yard. Audrey stuck out her tongue to catch raindrops. The rain didn’t last long, but it was enough to make the tin walls of the house glisten.

Douglas was inside, playing with kittens that belonged to Jessie, the sister with the missing tooth.

‘Do you get rain up your way?’ asked Boy, his mouth full of yellow scone.

‘Not too often.’ Audrey licked butter from the corner of her mouth. The scone was delicious, but not quite as light as the ones her mum made.

The door behind them flew open. Douglas stood there with his hands on his hips. ‘Audwey, are snails poison?’

‘No, I don’t think so.’

‘Good, cos I kissed one.’ The door slammed again, followed by the sound of running feet.

Audrey looked at Boy and remembered Mrs Paterson’s remark about runny noses being a bad habit. ‘You’ve got a foydool on your cheek.’

‘What?’

Audrey tapped her cheek to show him which side of his face was smeared. Boy wiped his cheek with one sleeve.

‘That’s a word Mrs Paterson told me.’

Parker bounced a ball off a side wall of the house. Then a scuffed shoe came hurtling out of an open window. A girl climbed out after it.

‘Is Mrs P as scary as she looks?’ asked Boy.

‘I think she’s sad.’ Audrey said nothing about the crying she had heard late at night. ‘But she’ll be happier now because I’m her project.’

‘What’s that mean?’

‘I have to say

please

and

thank you

and learn to knit bunny holes.’

‘I wouldn’t want to be a project if you had to knit.’ Boy rolled his eyes. ‘Me dad reckons he’s seen better heads than Mrs Paterson’s on his beer.’

Two of the brothers—Audrey couldn’t remember their names—began a mock sword fight with sticks in the backyard.

‘Are there lots of children at the school?’ asked Audrey.

‘About twenty, if everyone turns up.’

‘Do you like school?’

‘There are

some

good things. Our last teacher had some of those cycle-pedia books. My favourite part was about William the Conqueror. He wore a metal hat that came down over his nose and he got to be King of England.’

‘My mum teaches me,’ said Audrey. ‘But we haven’t done conquerers yet.’

‘William the Conqueror blew up at his funeral. They tried to make him look like he wasn’t dead. But they didn’t do it right. You know, like stuffin’ a bird.’

‘My brother, Price, skins rabbits.’ Audrey thought for a moment. ‘Was the Conqueror wearing his nose-hat when he exploded?’

‘Don’t know. That teacher left Beltana and she took her cycle-pedias with her.’

‘We’re friends now, aren’t we?’ asked Audrey.

‘Reckon so.’

‘Would you help me do something?’ she said. ‘It might get us in trouble.’

Twenty-three

Audrey stood outside the hospital and looked up at the sky. Dark grey clouds promised more rain. Audrey’s blue dress was measled with wet dots.

‘

Aaah.

’ Boy bent over, clutching his stomach. ‘

Ooh.

’

Audrey frowned.

Boy straightened up. ‘I’m just practisin’.’

His rehearsal was so real that it had tricked Audrey for a moment.

‘Let’s do it now,’ she said. ‘Me and Dougie have to be back at Mrs Paterson’s soon. Are you really sure it’s that window?’

‘Yes. I looked through it once. Hughie dared me. They named this new part of the hospital after a lady that died. Her name was Amy Fairfax. The nursing sisters put ladies and babies in there.’

Dragging one leg, Boy limped forward.

‘

Psst

.

Boy

. You’re supposed to have a sore stomach. Not a broken leg.’

He nodded but kept the limp.

Audrey began counting.

Boy disappeared around the back of the hospital. Before Audrey even got to a hundred, she heard him give a loud yell.

There were only two nursing sisters in Beltana. If Boy made enough noise, they should both run out to see what was wrong. Audrey crossed her fingers. She heard Boy complaining loudly about pains in his stomach. He was making more racket than a flock of cockatoos.

Audrey sneaked past the rainwater tank and behind some scraggly bushes, heading towards the women’s ward. She checked left, and then right, to make sure no one was watching, then peered through the window. There were several beds, but only two had people in them—Audrey’s mother and one other woman.

It was polite to knock when you wanted to walk through someone’s door. Audrey supposed it was the same for climbing through a window. She rapped on the glass, slid the window open, then hooked one leg over the sill.

Twenty-four

Mum’s face was as pale as the sheet that covered her. She sat, propped against pillows in a high iron bed.