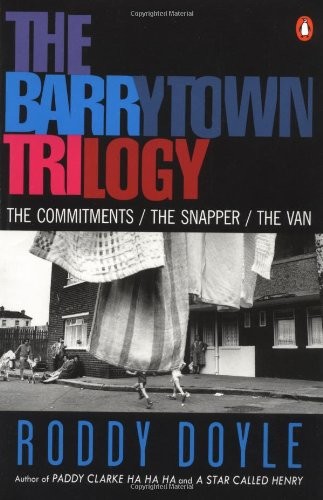

The Barrytown Trilogy

ONTENTS

About the Book

This volume brings together under one cover Roddy Doyle’s three acclaimed novels about the Rabbite family from Dublin.

The Commitments

traces the rapid rise and even more rapid fall of Jimmy Rabbite Jr’s unusual soul band. In

The Snapper

, Sharon Rabbite’s pregnancy sparks off intense speculation among her friends and family, but she is determined to reveal the identity of the father in her own time.

The Van

, set during Ireland’s 1990 World Cup attempt, follows the fortunes of Jimmy Sr and his friend Bimbo as they launch their travelling fish‘n’chip shop on an unsuspecting Barrytown, learning much about themselves in the process.

Roddy Doyle was born in Dublin in 1958. He is the author of nine acclaimed novels including the Barrytown Trilogy, two collections of short stories,

Rory & Ita

, a memoir about his parents, and most recently,

Two Pints

, a collection of dialogues. He won the Booker Prize in 1993 for

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

.

Novels

The Commitments

The Snapper

The Van

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

The Woman Who Walked Into Doors

A Star Called Henry

Oh, Play That Thing

Paula Spencer

The Dead Republic

Bullfighting

Two Pints

Non-Fiction

Rory & Ita

Plays

Brownbread

War

Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner

The Woman Who Walked Into Doors

The Government Inspector

(translation)

For Children

The Giggler Treatment

Rover Saves Christmas

The Meanwhile Adventures

Wilderness

Her Mother’s Face

A Greyhound of a Girl

This book is dedicated to

My Mother and Father

Honour thy parents, Brothers and Sisters. They were hip to the groove too once you know. Parents are soul.

Joey the Lips Fagan

T

HE

B

ARRYTOWN

T

RILOGY

The Commitments

The Snapper

The Van

—SOMETIMES I FEEL SO NICE—

GOOD GOD———

I JUMP BACK——

I WANNA KISS MYSELF————!

I GOT—

SOU—OU—OUL—

AN’ I’M SUPERBAD———

James Brown,

Superbad

—We’ll ask Jimmy, said Outspan. —Jimmy’ll know.

Jimmy Rabbitte knew his music. He knew his stuff alright. You’d never see Jimmy coming home from town without a new album or a 12-inch or at least a 7-inch single. Jimmy ate Melody Maker and the NME every week and Hot Press every two weeks. He listened to Dave Fanning and John Peel. He even read his sisters’ Jackie when there was no one looking. So Jimmy knew his stuff.

The last time Outspan had flicked through Jimmy’s records he’d seen names like Microdisney, Eddie and the Hot Rods, Otis Redding, The Screaming Blue Messiahs, Scraping Foetus off the Wheel (—Foetus, said Outspan. —That’s the little young fella inside the woman, isn’t it?

—Yeah, said Jimmy.

—Aah, that’s fuckin’ horrible, tha’ is.); groups Outspan had never heard of, never mind heard. Jimmy even had albums by Frank Sinatra and The Monkees.

So when Outspan and Derek decided, while Ray was out in the jacks, that their group needed a new direction they both thought of Jimmy. Jimmy knew what was what. Jimmy knew what was new, what was new but wouldn’t be for long and what was going to be new. Jimmy had Relax before anyone had heard of Frankie Goes to Hollywood and he’d started slagging them months before anyone realized that they were no good. Jimmy knew his music.

Outspan, Derek and Ray’s group, And And And, was three days old; Ray on the Casio and his little sister’s glockenspiel,

Outspan on his brother’s acoustic guitar, Derek on nothing yet but the bass guitar as soon as he’d the money saved.

—Will we tell Ray? Derek asked.

—Abou’ Jimmy? Outspan asked back.

—Yeah.

———Better not. Yet annyway.

Outspan was trying to work his thumb in under a sticker, This Guitar Kills Fascists, his brother, an awful hippy, had put on it.

—There’s the flush, he said. —He’s comin’ back. We’ll see Jimmy later.

They were in Derek’s bedroom.

Ray came back in.

—I was thinkin’ there, he said. —I think maybe we should have an exclamation mark, yeh know, after the second And in the name.

—Wha’?

—It’d be And And exclamation mark, righ’, And. It’d look deadly on the posters.

Outspan said nothing while he imagined it.

—What’s an explanation mark? said Derek.

—Yeh know, said Ray.

He drew a big one in the air.

—Oh yeah, said Derek. —An’ where d’yeh want to put it again?

—And And,

He drew another one.

—And.

—Is it not supposed to go at the end?

—It should go up his arse, said Outspan, picking away at the sticker.

* * *

Jimmy was already there when Outspan and Derek got to the Pub.

—How’s it goin’, said Jimmy.

—Howyeh, Jim, said Outspan.

—Howayeh, said Derek.

They got stools and formed a little semicircle at the bar.

—Been ridin’ annythin’ since I seen yis last? Jimmy asked them.

—No way, said Outspan. —We’ve been much too busy for tha’ sort o’ thing. Isn’t tha’ righ’?

—Yeah, that’s righ’, said Derek.

—Puttin’ the finishin’ touches to your album? said Jimmy.

—Puttin’ the finishin’ touches to our name, said Outspan.

—Wha’ are yis now?

—And And exclamation mark, righ’? ——And, said Derek.

Jimmy grinned a sneer.

—Fuck, fuck, exclamation mark, me. I bet I know who thought o’ tha’.

—There’ll be a little face on the dot, righ’, Outspan explained.

—An’ yeh know the line on the top of it? That’s the dot’s fringe.

—Black an’ whi’e or colour?

—Don’t know.

—It’s been done before, Jimmy was happy to tell them. —Ska. Madness, The Specials. Little black an’ whi’e men. ———I told yis, he hasn’t a clue.

———Yeah, said Outspan.

—He owns the synth though, said Derek.

—Does he call tha’ fuckin’ yoke a synth? said Jimmy. —Annyway, no one uses them annymore. It’s back to basics.

—Just as well, said Outspan. —Cos we’ve fuck all else.

—Wha’ tracks are yis doin’? Jimmy asked.

—Tha’ one, Masters and Servants.

—Depeche Mode?

—Yeah.

Outspan was embarrassed. He didn’t know why. He didn’t mind the song. But Jimmy had a face on him.

It’s good, tha’, said Derek. —The words are good, yeh know ——good.

—It’s just fuckin’ art school stuff, said Jimmy.

That was the killer argument, Outspan knew, although he didn’t know what it meant.

Derek did.

—Hang on, Jimmy, he said. —That’s not fair now. The Beatles went to art school.

—That’s different.

—Me hole it is, said Derek. —An’ Roxy Music went to art school an’ you have all their albums, so yeh can fuck off with yourself.

Jimmy was fighting back a redner.

—I didn’t mean it like tha’, he said. —It’s not the fact tha’ they went to fuckin’ art school that’s wrong with them. It’s —(Jimmy was struggling.) —more to do with —(Now he had something.) ——the way their stuff, their songs like, are aimed at gits like themselves. Wankers with funny haircuts. An’ rich das. ——An’ fuck all else to do all day ’cept prickin’ around with synths.

—Tha’ sounds like me arse, said Outspan. —But I’m sure you’re righ’.

—Wha’ else d’yis do?

—Nothin’ yet really, said Derek. —Ray wants to do tha’ one, Louise. It’s easy.

—Human League?

—Yeah.

Jimmy pushed his eyebrows up and whistled.

They agreed with him.

Jimmy spoke. —Why exactly ——d’yis want to be in a group?

—Wha’ d’yeh mean? Outspan asked.

He approved of Jimmy’s question though. It was getting to what was bothering him, and probably Derek too.

—Why are yis doin’ it, buyin’ the gear, rehearsin’? Why did yis form the group?

—Well———

—Money?

—No, said Outspan. —I mean, it’d be nice. But I’m not in it for the money.

—I amn’t either, said Derek.

—The chicks?

—Jaysis, Jimmy!

—The brassers, yeh know wha’ I mean. The gee. Is tha’ why?

———No, said Derek.

—The odd ride now an’ again would be alrigh’ though wouldn’t it? said Outspan.

—Ah yeah, said Derek. —But wha’ Jimmy’s askin’ is is tha’ the reason we got the group together. To get our hole.

—No way, said Outspan.

—Why then? said Jimmy.

He’d an answer ready for them.

—It’s hard to say, said Outspan.

That’s what Jimmy had wanted to hear. He jumped in.

—Yis want to be different, isn’t tha’ it? Yis want to do somethin’ with yourselves, isn’t tha’ it?

—Sort of, said Outspan.

—Yis don’t want to end up like (he nodded his head back) —these tossers here. Amn’t I righ’?

Jimmy was getting passionate now. The lads enjoyed watching him.

—Yis want to get up there an’ shout I’m Outspan fuckin’ Foster.

He looked at Derek.

—An’ I’m Derek fuckin’ Scully, an’ I’m not a tosser. Isn’t tha’ righ’? That’s why yis’re doin’ it. Amn’t I righ’?

—I s’pose yeh are, said Outspan.

—Fuckin’ sure I am.

—With the odd ride thrown in, said Derek.

They laughed.

Then Jimmy was back on his track again.

—So if yis want to be different what’re yis doin’ doin’ bad versions of other people’s poxy songs?

That was it. He was right, bang on the nail. They were very impressed. So was Jimmy.

—Wha’ should we be doin’ then? Outspan asked.

—It’s not the other people’s songs so much, said Jimmy. —It’s which ones yis do.

—What’s tha’ mean?

—Yeh don’t choose the songs cos they’re easy. Because fuckin’ Ray can play them with two fingers.

—Wha’ then? Derek asked.

Jimmy ignored him.

—All tha’ mushy shite abou’ love an’ fields an’ meetin’ mots in supermarkets an’ McDonald’s is gone, ou’ the fuckin’ window. It’s dishonest, said Jimmy. —It’s bourgeois.

—Fuckin’ hell!

—Tha’ shite’s ou’. Thank Jaysis.

—What’s in then? Outspan asked him.

—I’ll tell yeh, said Jimmy. —Sex an’ politics.

—WHA’?

—Real sex. Not mushy I’ll hold your hand till the end o’ time stuff. ——Ridin’. Fuckin’. D’yeh know wha’ I mean?

—I think so.

—Yeh couldn’t say Fuckin’ in a song, said Derek.

—Where does the fuckin’ politics come into it? Outspan asked.

—Yeh’d never get away with it.

—Real politics, said Jimmy.

—Not in Ireland annyway, said Derek. —Maybe England. But they’d never let us on Top o’ the Pops.

—Who the fuck wants to be on Top o’ the Pops? said Jimmy.

Jimmy always got genuinely angry whenever Top of the Pops was mentioned although he never missed it.

—I never heard anyone say it on The Tube either, said Derek.

—I did, said Outspan. —Your man from what’s their name said it tha’ time the mike hit him on the head.

Derek seemed happier.

Jimmy continued. He went back to sex.

—Believe me, he said. —Holdin’ hands is ou’. Lookin’ at the moon, tha’ sort o’ shite. It’s the real thing now.

He looked at Derek.

—Even in Ireland. ———Look, Frankie Goes To me arse were shite, righ’?

They nodded.

—But Jaysis, at least they called a blow job a blow job an’ look at all the units they shifted?

—The wha’?

—Records.

They drank.

Then Jimmy spoke. —Rock an’ roll is all abou’ ridin’. That’s wha’ rock an’ roll means. Did yis know tha’? (They didn’t.) —Yeah, that’s wha’ the blackies in America used to call it. So the time has come to put the ridin’ back into rock an’ roll. Tongues, gooters, boxes, the works. The market’s huge.

—Wha’ abou’ this politics?

—Yeah, politics. ——Not songs abou’ Fianna fuckin’ Fail or annythin’ like tha’. Real politics. (They weren’t with him.) —Where are yis from? (He answered the question himself.) —Dublin. (He asked another one.) —Wha’ part o’ Dublin? Barrytown. Wha’ class are yis? Workin’ class. Are yis proud of it? Yeah, yis are. (Then a practical question.) —Who buys the most records? The workin’ class. Are yis with me? (Not really.) —Your music should be abou’ where you’re from an’ the sort o’ people yeh come from. ———Say it once, say it loud, I’m black an’ I’m proud.

They looked at him.

—James Brown. Did yis know ———never mind. He sang tha’. ———An’ he made a fuckin’ bomb.