The Battle for Gotham (22 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

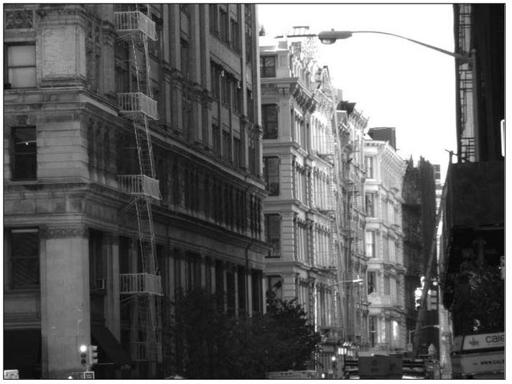

4.1 SoHo actually has quite a variety of buildings in scale and style.

Jared Knowles

.

In February 1973 I wrote a story noting that almost three years after a public hearing, the Landmarks Preservation Commission still seemed to be a long way from designating SoHo a historic district and formally recognizing the unique character of its mid-nineteenth-century Cast Iron architecture.

SoHo takes its name from its location south of Houston Street and has the largest concentration in the country of Cast Iron architecture, one of the few original American contributions to architectural history. Few people even knew about Cast Iron buildings until the effort to save this substantial collection of them was initiated by a determined local resident, Margot Gayle. Gayle, a longtime Village resident, formed the Friends of Cast Iron to advocate for designation of the twenty-six-block area, circulated petitions, and educated the public unaware of the district’s value.

Cast Iron refers as much to a method of construction as an actual architectural style. It was an early form of modular construction and a product of the Industrial Revolution. The facades of buildings—including the Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian columns and all the intricate ornamental details—were cast in off-site New York foundries and assembled on the building sites, in much the same way prefabricated building is done today.

It was then both economical and efficient for commercial buildings because the extra strength of iron allowed larger window and interior spaces. In the nineteenth century, SoHo was New York’s wholesale textile center, with display areas dominating ground floors and storage space above. Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, St. Louis, Baltimore, and a host of other cities followed New York’s lead and built Cast Iron buildings in the nineteenth century, but most of these areas outside of New York have been substantially destroyed. Remnants of such districts in cities across the country have since seen a renaissance following SoHo’s. Where they survive, their preservation and reuse reflect a national phenomenon.

THE DEATH-THREAT SYNDROME

Robert Moses, the Lower Manhattan Expressway’s primary planner and advocate, had the area declared “blighted” in the 1950s. That designation was essential to condemn private property for the highway.

Blight

is as subjective a term as

slum

, as described in the previous chapter. And clearly, one can recognize how hollow was the term as applied to this area when one recognizes the solidity of the buildings since renovated. All of the upgrades now making SoHo so expensive could occur only after the expressway and blight designation were defeated.

The expressway would have wiped out what is now SoHo, even though scores of thriving businesses still filled the buildings that were so functionally flexible. But the designation of blight was the death knell for the neighborhood, a guarantee of accelerated decay. As Jacobs observed in our conversation about the expressway fight:

Sure, a scheme like that either causes or accelerates deterioration. Businesses leave when they see the handwriting on the wall or don’t even try to establish themselves in such a location. Property owners hold out for the lucrative buyout. It’s a miracle when a place like the North End in Boston or the West Village keeps on improving and people keep putting money in when a death sentence hangs over it. They can only do it with the courage of knowing that they aren’t going to allow that death sentence. Or being totally ignorant that it exists.

But the bankers are never ignorant about it and stop giving loans. When there’s a death sentence like that on an area, you always have to work around it and get odd bits of money and so forth, which can make a very good area in the end, if it’s done.

4.2 Cast-iron facades distinguish most SoHo buildings and did in the demolished areas as well.

Jared Knowles.

“Odd bits of money” traditionally meant drawing on family and friends.

To make way for the planned ten-lane expressway and housing projects, forty-five acres of five- to six-story factory buildings (no higher than a hook-and-ladder fire truck could reach) were marked for extinction. “Hell’s 100 Acres,” the area was called by the fire department. Fires were common in the warehouses and small factories, and fire officials labeled the buildings firetraps. However, the activity in those buildings, not the buildings themselves, caused the fires. Code enforcement, not demolition, was called for. Factory floors were often piled with rags, garment scraps, bales of paper, open cans of chemicals, and other flammable objects. But the fire officials’ assessments fed right into the general public impression of the area as filled with derelict and discardable buildings.

In the 1960s the area became known as “the Valley” because its vast stock of low-rise industrial buildings lay between the skyscrapers of Wall Street and midtown. From the distance, the Manhattan skyline gives the impression of two separate cities, with a vast empty space between them.

Once the massive clearance projects were unveiled, this until then economically and socially viable district was doomed. This is the

death-threat syndrome

, also known as

planners’ blight

. Any residential, commercial, or industrial area begins to die once a new destiny is planned for it. Property owners cease maintenance, anticipating condemnation and demolition. Banks won’t lend money, even if property owners are inclined to invest. Businesses move out, not waiting for the battle to play out. In this case, few expected the plans to be canceled. Defeating highway and urban renewal plans was almost unthinkable at the time. Even if an announced plan eventually fails, the announcement alone has already killed a district or catalyzed its decline.

These kinds of plans are like a big billboard with a message to property owners: no future for this area, disinvest, cash out, leave. City services diminish. Activity spirals downward. This happens today, in New York and elsewhere, when big plans for stadia, mixed-use projects, and convention, entertainment, or retail centers and the like are announced. The decline of the targeted neighborhood becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. This is what happened to the South Houston Industrial Area that became SoHo. The death-threat syndrome killed it, not natural decay. Many experts tried to identify it otherwise. Many still do.

It is contradictory to label as dead or a slum any district where buildings are occupied, businesses function, and an economic ebb and flow exist. Any neighborhood witnessing sustained economic activity and new businesses moving in can’t be honestly declared blighted. This defies reason and economic logic. But it is still happening now in New York and elsewhere despite the lessons of the late twentieth century, as shown in different chapters of this book. Unfortunately, the leniency of the law simply allows a municipality to declare an area blighted on very loose standards.

THE EXPRESSWAY FIGHT

The expressway had been planned and talked about since the 1940s, but was formally unveiled in 1959. The 1956 Federal Interstate Highway Act, with its 90 percent federal funding, gave highway planners the opportunity to implement scores of road projects long on the drawing boards. Jacobs got involved in 1962. During the West Village Urban Renewal fight in which she was so engaged, urban renewal and highway hearing dates would occasionally coincide. Thus, Villagers, like Jacobs, would hear informally about the expressway fight. “There was so little in the newspapers that I wouldn’t have been aware that it was going on if I hadn’t run into people in City Hall,” Jacobs recalled. “That’s how badly it was being covered. It wasn’t regarded really as news.”

Although the expressway had been in the planning for years, it really drew attention in the late 1950s or very early ’60s. The process accelerated with the expropriation of property, vacating of buildings, and eviction of people. Jacobs got involved when Father LaMountain from the Church of the Most Holy Crucifix on Broome Street in Little Italy called her. “He and his parishioners had been fighting it,” she said. “It would wipe out his street, church, parishioners, shops, and more. This was right after our West Village fight, and we’d won it, so he asked me if I would come to a meeting on this in early ’62. I was reluctant. I had put in a horrendous year. We didn’t get the West Village Urban Renewal designation removed until February ’62. It was a whole year.” Sleepless nights, skipped family meals, and dining room meetings marked the year. The Jacobs family had a signal to their cohorts: if the porch light was on, neighbors were welcome; if off, privacy requested. “There were meetings going on all the time. Most of the time, everybody was at work. Only in the evening could we do these things, so that’s the kind of year the whole family had. And we wouldn’t have missed it. I mean, we’d all love to have missed having the problem, but as long as we had it, we wouldn’t have missed fighting and winning it. No question about that. But we were pretty tired, and the idea of another fight. . . . So it took some persuasiveness on the part of Father LaMountain to have me just come to the meeting.”

That meeting in the spring of 1962 was the first time she realized the expressway was connected with the earlier fight to keep the road out of Washington Square. “We fought that very hard, beginning back in ’56,” she said. “Now I began to understand that this was connected. And if this expressway came through, our victory in Washington Square was a very Pyrrhic one. The ramps would be coming off, and if they didn’t come off through Washington Square, they’d come off damn close and in other places in the Village too. These monsters come back, you know.”

The larger citywide agenda of Moses and city officials slowly became visible. They had heard about a map in David Rockefeller’s Lower Manhattan Development Office. “It showed all the redone things, combinations of highways and new real estate developments on both sides of Manhattan, all the way up the West Side. So I began to see that these were other facets of the very same fight, that somebody had a great vision of how New York was to be. We kept running into this vision, and it was a monstrous vision. You would see this piece of it and that piece of it, and it wasn’t paranoid to think that it was an overall plan that the public really didn’t know that much about. It was clear what a disaster it would portend for the Village and other neighborhoods.” A built Lower Manhattan Expressway would have relegated the city to neighborhood fragments scattered between and within the clover leafs. His only goal: efficiency for moving automotive traffic. Cities, he believed, should serve traffic. This does not make for a strong city.

It had not been long since

Death and Life

was published in 1961. She had finished it just before the West Village fight. “Thank God,” she said with a great sigh. “If I’d had to give that much time to the fight, I’d have had to drop the book. I finished it in January, went back to work at

Architectural Forum

, and in February the West Village fight began. The book was published in October 1961.”

The conflict seemed right out of the pages of her book. She agreed. “It was even much worse than I had ever believed or dreamed when I was writing the book. I couldn’t believe there would’ve been this much stupidity about New York.”

At Father La Mountain’s meeting, everybody said the expressway was inevitable. “All of our elected officials, because they knew how unpopular it was, were always going on record against it,” she remembered, “but were never doing a thing to stop it and were always preaching defeatism. Moses was the real promoter, joined by all the traffic and highway people, the Regional Plan Association, the Planning Commission. Mayor Wagner seemed to be for it, but with Wagner, a wonderful thing happened. We had a hearing, and we actually changed the mind, as far as one can tell, of the Board of Estimate.” The hearing was a day or two before Christmas, not an uncommon ploy to ensure poor public turnout. “Well, instead we neglected our Christmas. I even feel bitter about that to this day, that they stole one of my Christmases from me. Well, they didn’t really. We ended up with a great Christmas present.” The issue, she recalled, was probably the expropriation of the land, funds, and authorization for it. “It was one of the big steps,” she said. “Once that was okayed, it was the point of no return.”