The Battle for Gotham (41 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

In the end, will Westway be remembered as but a symbol of abstract and competing concepts of urban renewal—the automobile against mass transit; the slow-growth philosophy of targeted renaissance against the glamour of grand-scale construction? Indeed, will it be remembered at all?

SAM ROBERTS,

“Battle of the Westway: Bitter 10-Year Saga of

a Vision on Hold,” New York Times

J

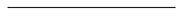

ane Jacobs sits at the dining room table of her three-story Victorian house in the leafy Toronto neighborhood known as the Annex. It is 1978. She is pondering the news I am bringing her from New York City, primarily the latest chapters in the ongoing fight over the Westway—the massive replacement of the West Side Highway along the Hudson River—then raging in New York. Her white hair and large eyeglasses give her an owlish look that can turn from severity to impishness at the switch of urban topic. “Why aren’t you writing about this, Roberta?” she asks in her most challenging voice. Her unrelenting gaze remains fixed on me.

8.1 Jane loved to sit and chat on her front porch, which we did many times.

Herschel Stroyman

.

This is my third or fourth visit since being introduced to her earlier that year by the first editor of my first book, Jason Epstein, Jacobs’s editor.

1

We had just begun a long friendship from which I benefited enormously. Over twenty-eight years, she nurtured, nudged, challenged, and enriched my own thinking, writing, and activism. She reinforced my skepticism of official city planning precepts, occasionally rescued me from acceptance of a misguided notion, and showed me the universal lessons of Toronto’s enduring urbanism. Her willingness to take controversial stands and to contradict conventional wisdom was an inspiration for my own activism. We had our differences that only made our conversations more lively. Jacobs and her family had moved to Toronto in 1968. She, more than anyone, opened my eyes early to the defining impact of transportation and manufacturing issues on cities.

On this occasion, our mutual friend Mary Nichols was also visiting. Nichols, a resident of Greenwich Village and former columnist for the

Village Voice

and then an assistant to Mayor Kevin White in Boston, had kept the expressway in the news through her

Village Voice

coverage when the mainstream press was less interested and editorially supportive.

Both Jacobs and Nichols were intensely concerned about the Westway progress. They both saw a direct link to the Moses Lower Manhattan Expressway. Jacobs and her family had moved to Toronto in 1968 during the Vietnam War when her two sons were draft age. The final defeat of the Lower Manhattan Expressway occurred after her 1968 departure. Nichols was working and living in Boston and would return to New York soon to work for her old friend and mayor-elect Ed Koch. Yet both urban activists still cared deeply about New York.

On this particular visit, Jacobs and Nichols both grilled me about the Westway fight and persuaded me to write about Westway—the twelve-lane highway proposed to be built on landfill along the West Side of Manhattan—when criticism of it in the press was rare.

2

Did I know how critical it was to the future of New York? Did I realize how important to a city its public transit is? Did I realize that so many American cities were dysfunctional because they had spent decades investing in automobile access while destroying the neighborhoods, downtowns, and transit systems they all once had? Did I realize that New York could go in the same direction? No. I had not realized any of these things to the extent they were presenting them. My focus was on neighborhood and downtown regeneration around the country: the South Bronx, Savannah, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, San Francisco, Seattle, and elsewhere. I had just started research for my first book,

The Living City: Thinking Small in a Big Way

(1989).

I had been coming to Toronto to explore causes of recent urban decay with Jane, as well as to share with her the signs of rebirth that I was observing in my research but that conventional observers and professionals were dismissing as ad hoc and too inconsequential. She was so enthusiastic about what I was describing as the early rebirth of the South Bronx generated by community-based improvisations that she insisted I take her there when she was next in New York. We subsequently visited the People’s Development Corporation and Banana Kelly in the South Bronx in 1978, led by Ron Shiffman, then head of the Pratt Center for Community and Economic Development, who first took me there in 1977.

She was, however, relentless in pushing me to stop and write about Westway. In many ways, the most important aspect of our expanding relationship was her willingness to be critical of what I was saying or thinking. My slowness to recognize the significance of Westway was one of those occasions. Sure, transit was an important issue in the urban regeneration story, but I did not yet view it as an overarching one. Jane and Mary turned my head on this topic. Transportation, they convinced me, was central to the economic, physical, and social life of all of urban America.

Persuaded, I decided to switch gears. Michael Kramer, then an editor at

New York Magazine

, liked the subject, if I could get Jane to consent to an interview on it. A few months later, she agreed. These kinds of interruptions were intolerable when she was writing. Consenting to this interview, however, was not just rare but sudden, and I asked why. “Westway is different,” she said. “I just think it’s the single most important decision that New York is facing about its future and whether it can possibly reverse itself, or whether it’s hopeless,” she explained. “This is in part because of the practical damage that Westway will do to the city. And it’s also very important as a symptom of whether New York can profit by the clear mistakes and misplaced priorities that it’s had in the past or whether it just has to keep repeating them.”

Her son Jimmy, who lives down the block, told her she was crazy to agree to this interview. “But I told him, ‘Jimmy, this is important for the fight, and what if that Westway is built and I think, ‘Maybe I could have made some difference; I can’t live with that.’ And he said, ‘Ah yeah, sure,’” she laughed.

We spent many hours over several visits discussing this subject, all of which was taped (the tapes were transcribed).

3

The substance went way beyond Westway. She talked a lot about recent New York development history, providing tales and tidbits she had never written or spoken about.

Jacobs’s art is to accessibly outline a specific issue while making clear the broader implications of the substance. So much of what she covered when referring to either the Lower Manhattan Expressway or Westway—like every other issue she wrote or talked about—can be applied to highway and urban renewal fights anywhere.

At its simplest, Westway was just another piece of the Interstate Highway System, stretching from Forty-second Street down to the island’s tip. The complexities are not visible at first. No neighborhoods would have been bisected or erased, although plenty would suffer through the increased traffic of the expanded highway. No land would have been taken away. In fact, land would be added with landfill under which the highway would partially go through a tunnel. Together with the six-lane inland service road, Westway would equal twelve lanes. On top of the landfill, two hundred acres of new city would be created for housing, parks, and commercial development. New highway proposals across the country often looked that simple. Sometimes they still do. Deceptively, the Westway route was drawn as a straight line on all maps. The highly land-consumptive on-and off-ramps were rarely shown. Only two ramps were apparently planned, but it wasn’t clear if more would have been added.

8.2 Jane took special pleasure in the view from her porch down through the whole row of porches.

Herschel Stroyman.

As she proceeded through this conversation, Jacobs primarily explained the damage Westway would inflict on New York City and how it would transform the city. But she went way beyond this as well. Most significantly, Jacobs illustrated the importance of any highway debate to the future shape of all cities of any size. This was long before this fundamental debate went mainstream. Essentially, how one views a highway proposal directly relates to one’s fundamental understanding of how a city functions best.

THE HEART OF THE ARGUMENT

Two fundamental points formed the heart of her argument against Westway. The first is that Westway was part of the same original overall highway network plan of 1929, as was the Lower Manhattan Expressway, thus their intrinsic connection. That plan for all of Manhattan, she argued, improperly favored development geared toward the car, not mass transit or the pedestrian. The second point was the internal contradiction between economics and the environment evident in the argument for both highways. “These are really very obvious things, but I don’t think they’re obvious to most of the public,” she said. “The first point is that Westway is only part of the 1929 plan. Just think of that. It’s almost fifty years old, almost half a century old. New York prides itself on being up to date, but it’s being run by a half-century-old plan. Only pieces of it keep surfacing. Nobody would ever consent to the insanity of doing the entire thing. And yet, if, piece by piece, it gets done, the whole thing is inevitable, because each part depends on another.”

In this case, if Westway were built, the same expanded highway would inevitably be necessary from Forty-second Street north and from the Battery south around and up the East Side. Robert Caro, she pointed out, illustrates well in

The Power Broker

the Moses technique of building a bridge without saying there’s got to be a new or wider highway on either side. “And the bridge gets built,” she said, “and aha, now the wider highway becomes necessary. Or he builds a road and says nothing about a great big bridge that’s going to have to come, and aha, all of a sudden, the bridge is necessary. It’s piecemeal. People would have a fit if they saw the whole thing.” But, she said, that’s the way these highways have been pushed and not just in New York but everywhere. “In essence, the plan is a ring, an oval really, all around the outside of the island, and then it has lacings across the middle. It’s a net, catching Manhattan. The Lower Manhattan Expressway was one of these crosstown lacings for the whole system.”

During the fight over the Lower Manhattan Expressway, opponents had seen the 1929 Regional Plan, both the maps and the written volumes. This put their effort in perspective. The existing West Side Highway (six lanes) was the first piece of the plan, originally called the Miller Highway. The East River Drive (six lanes), built in the 1930s, was also part of it. “The plan ran into trouble when it began to involve the lacings across the city and the ramps off of them,” noted Jacobs. A crossing at Thirtieth Street was the first defeat, she said, because it would have destroyed the Little Church Around the Corner where many theatrical weddings took place. It had a loyal constituency.