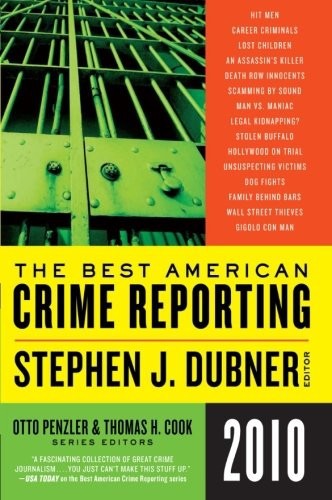

The Best American Crime Reporting 2010

Read The Best American Crime Reporting 2010 Online

Authors: Otto Penzler

Tags: #True Crime, #General

Guest Editor

Stephen J. Dubner

Series Editors

Otto Penzler and Thomas H. Cook

Otto Penzler and Thomas H. Cook |

Preface

Stephen J. Dubner |

Introduction

Calvin Trillin |

At the Train Bridge

Rick Anderson |

Smooth Jailing

Kevin Gray |

Sex, Lies, & Videotape

David Grann |

Trial by Fire

Pamela Colloff |

Flesh and Blood

Jeffrey Toobin |

The Celebrity Defense

Nadya Labi |

The Snatchback

Peter Savodnik |

The Chessboard Killer

Maximillian Potter |

The Great Buffalo Caper

Ernest B. Furgurson |

The Man Who Shot the Man Who Shot Lincoln

David Kushner |

The Boy Who Heard Too Much

Skip Hollandsworth |

Bringing Down the Dogmen

Charles Bowden |

The Sicario

C

RIME IS ARGUABLY CHIEF

among our tragedies because it is not encoded within the human experience in the way that death is encoded in every living cell. We are not genetically fated either to commit or to suffer crime. In the vast majority of cases, it is an act first grimly willed, then either meticulously or haphazardly plotted, then finally, in the absence of an outwardly staying hand or an inwardly reasoning thought, cold-bloodedly carried out. Crime is seldom a response to a fleeting itch, but rather the product of an insistent urge, say, to make money without working for it or to eliminate a rival by killing rather than outthinking him. For the most part, crime doesn’t strike impersonally, like a virus, nor in response to any actual physical appetite, as a leopard kills a deer. For that reason, it often victimizes people because they possess otherwise desirable qualities. It is beauty that catches the eye of the sex-enslaver. It is the wallet of an honest worker that attracts the mugger’s hand.

The hungers that cause crime are rarely biological. Who robs a bank in order to buy a sandwich or murders a prostitute for lack of sex? There is little doubt that crime is sometimes the product of mental disease, of course, but mental disorder can no less easily drive men to acts of nobility and courage. Who can doubt, for example, that the man who killed John Wilkes Booth was completely out of his mind?

A criminal act almost always resides at some point on the spectrum of personal selfishness. Responding to a selfish urge, an esteemed financial advisor decides upon a course that will create a monster of mendacity, and the likes of Bernie Madoff suddenly sprouts among us. On a quiet street in Greenwich Village, a man sees a little boy on his way to school and decides that his own momentary sexual release is worth the whole life of a child. A Russian housing development becomes a killing field when a nondescript neighbor repeatedly follows an appetite whose satisfaction neither feeds nor clothes him, but whose dark allure seems almost as irresistible.

As a form of selfishness, crime is marked by a peculiar incapacity to delay gratification. In a luxurious house with a sparkling pool, a famous man chooses a route that will lead him to public infamy and lifelong exile because he cannot deny himself the fleeting ecstasy of a spasm. In a world so far from this it seems hardly possible that it occupies the same planet, a teenage girl plots the slaughter of her family because she cannot delay an independence that would but shortly have been hers. On an isolated train bridge, a young man cannot bear another moment without asserting himself, and finds the most immediate tool of that assertion in a loaded gun.

Because most crime is simply one form or another of selfish human action, its sources are generally quite clear. Criminals are known for many things, but subtlety and nuance are not among them. When a gang of bunglers steals a rack of buffalo bones, one does not assume an irrepressible interest in the physiology of mammoths. But the very same motive can lead very different men to breed killer dogs or turn a few squalid rooms into a South of the Border torture chamber. It is not the nature of the motive but the extremity with which it is pursued that makes all the difference, and it is in that difference that the mystery of motivation actually resides. For why, in response to the same need to be noticed, does one young man create havoc with a gun while another does it with a computer? Why does one man seek only to steal the skeleton of a buffalo, while another (say, Vladimir Putin) wishes to steal the freedom of an entire people?

Crime, in the end, is human frailty writ large. But even in response to crime, that frailty presides. For how can any legal code deal with the passionate need of a parent to reclaim a kidnapped child? How can juries fail to be swayed by myth when it is clothed as expertise?

Such are the issues confronted and the questions raised in this year’s

Best American Crime Reporting

, a collection whose range and depth once again demonstrate the extraordinary contribution American crime reporting makes to our country’s contemporary literature, as well as to our ongoing concern for and analysis of man’s deepest needs and darkest acts. As a collection, and as a series, it continues to take man as man, neither less nor more than what his acts reveal, man for better and for worse, in sickness and in health, from this day forward and for evermore.

Thomas H. Cook

Otto Penzler

March 2010

Introduction

I

WILL NOT WASTE

much of your time describing the stories you will read in this collection. They are told so well, with such perverse attention to detail, that simply summarizing them would constitute a crime in itself.

I will, however, ask you to consider a few questions that came to mind while reading them. Such as:

What causes crime in the first place?

As the Great Recession of 2008 blasted into view, doleful prognosticators warned us that crime would surely spike. But it hasn’t. For a society that is rather obsessive about crime, it turns out we don’t know much about it. We assume that a bad economy inevitably leads to more crime, but in fact that is not so, especially for violent crime. The economy did quite well during stretches of the 1960s, when crime was rising fast, and once again during the late 1980s, which saw a crippling rise in crime.

So if a bad economy doesn’t cause crime, what does?

Unwantedness, for one. That’s right: unwanted children are more likely to turn into criminals than children whose parents want them badly. That’s why, as jarring as this may sound, the legalization of abortion in 1973 led to a lagged decrease in crime—because it afforded many women the opportunity to terminate unwanted pregnancies, resulting in a generation of children that came of age without some of its most vulnerable citizens.

Lax prosecution and sentencing also encourage crime. Many of us preserve a useful fiction that criminals are unlike you and me in every way, but they aren’t as different as we may wish—most centrally so in that they, like us, respond fiercely to incentives. When there is a weak incentive to not commit crimes, therefore, more crimes are committed. We saw this in much of the 1960s and 1970s, when judicial and civil rights reforms led to lower arrest rates, lower imprisonment rates, and shorter prison sentences.

Voila!

The perfect recipe for more crime. But this recipe was more recently reversed—and then some, with historically high rates of imprisonment. As a result:

voila!

again; crime fell.

As it happens, television also leads to crime. This is perhaps an even more controversial theory than the abortion theory, but the data strongly suggest it is true: children who grow up watching a lot of TV are more likely than other children to become criminals. The content itself, however, does not seem to be the culprit. Some people have long argued that violent TV shows lead to violent behavior, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Rather, it seems that children who take in a lot of TV from birth through age four—even the most innocuous, family-friendly fare—are more likely to engage in crime when they grow up. Why? It’s hard to say. Maybe kids who watch a lot of TV don’t get properly socialized, or never learn to entertain themselves. Perhaps TV makes the have-nots want the things the haves have, even if it means committing a crime to get them. Or maybe it has nothing to do with the kids at all; maybe it’s a case of Mom and Dad becoming derelict when they realize that watching TV is a lot more entertaining than taking care of the kids.

So now we know a bit about why the modern world is so drenched in crime.

Or

is

it?

The next time you’re at a bar or a dinner party, or wherever you convene with people who are willing to wager, try this one:

If you look at the homicide rate in, say, western Europe over the past six centuries, which century has the highest rate and which has the lowest?

You, dear reader, will likely win this bet, for the homicide rate in Europe was far higher in the fifteenth century than in the twentieth century—more than 40 times greater in Scandinavia and more than 15 times greater in Germany. Italy has seen the most amazing decline: there were 73 homicides per 100,000 people in the fifteenth century and fewer than 3 per 100,000 in the twentieth.

So perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong question all along. Rather than wonder why there’s so much crime in the world, perhaps we should ask why there’s so

little

. Isn’t it remarkable? Consider how many of us share this increasingly crowded and competitive planet—in the aftermath of a calamitous financial meltdown, no less—and then look at the numberless opportunities we forego daily to steal, cheat, lie, and even kill.

Why?

Alas, that is a question for philosophers, or someone with more advanced degrees than mine.

But here is what I find particularly interesting: we collectively seem unwilling, or unable, to fully accept the fact that there is less crime today than there used to be. A dramatic decrease in crime began in this country nearly twenty years ago. It is hard to remember just how welcome—and startling—this crime drop was. At the time, violent crime drove the public discourse; it led the nightly news and it dominated political conversations. The smart money said the problem would get only worse. And then, instead, the problem went into reverse. In 1991, the rate of violent crime was 758 per 100,000 people; by 2001, it had plunged to 507, a 33 percent decrease. (Property crime also fell, from 5,140 per 100,000 people to 3,568, a 30 percent drop.)

Crime has continued to fall in recent years, albeit not as extravagantly as during the 1990s—a decrease of about 10 percent over the past decade. The decline has continued even during the recession. But do you know what the pollsters tell us? They say that Americans are convinced that crime is on the rise once again. Data be damned, that’s what we think: the world is dangerous and getting more so, and we cannot be convinced otherwise.

Why on earth is this the case?

Perhaps we are still shaken up from those terrible high-crime decades and can’t believe those shadows are gone for good. Perhaps we have come to distrust the data the police cite. Or maybe the recession has been so depressing that we’ve lost the ability to see straight.

I have one more possibility: TV shows. Have you noticed how many crime shows are on TV these days? Here are the top twenty shows from the fall/winter 2008 season, with the crime shows bolded:

- Dancing with the Stars

- Dancing with the Stars Results

- CSI

- NCIS

- NBC Sunday Night Football

- The Mentalist

- Desperate Housewives

- 60 Minutes

- Criminal Minds

- Grey’s Anatomy

- CSI: NY

- Two and a Half Men

- CSI: Miami

- Without a Trace

- Survivor: Gabon

- Cold Case

- Eleventh Hour

- Biggest Loser 7

- 24

* - The OT

And here are the top twenty shows from the 1991–1992 TV season,

†

when actual crime was at its worst:

- 60 Minutes

- Roseanne

- Murphy Brown

- Cheers

- Home Improvement

- Designing Women

- Coach

- Full House

- Unsolved Mysteries

- Murder, She Wrote

- Major Dad

- NFL Monday Night Football

- Evening Shade

- Northern Exposure

- A Different World

- The Cosby Show

- Wings

- The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air

- America’s Funniest Home Videos

- 20/20

So there appears to be an inverse relationship between the amount of real crime in the U.S. and the number of popular TV shows about crime. And at this moment, crime seems to collectively captivate us well beyond the degree to which it actually exists. Why?

It may be that TV shows about murder and mayhem are more fun to watch when you’re not so worried about actually getting murdered. Our relative safety lets us appreciate horrific TV murders for what they are: fictional exaggerations of real-life anomalies. Like a shark attack or a $100 million lottery winner, a murder is far more unlikely than the media would have us believe.

The stories in this fine book similarly represent the anomalies—and that is why we love them. They represent the rare moments when the human psyche, despite all encouragement to the contrary, plows through the barrier of accepted behavior and becomes a killer or a con man or a remorseless brute. A few of these criminals are very well-known (Bernie Madoff and Roman Polanski), but most of them would have never gained our attention at all had they not done something so very rare.

The writing you will encounter is simply spectacular. Weird and mesmerizing and chilling and bold. Kevin Gray profiles Helg Sgarbi, a Swiss swindler who to Gray’s eyes (and, therefore, ours) doesn’t appear at all capable of seducing even one wealthy woman, much less a string of them. And yet, in one of the most delicious kickers I have ever read, Sgarbi even seems to get his hooks into Christine, “the thirty-something German translator I’ve brought to facilitate dealings with the prison guards.” Upon leaving the prison, Christine admits as much to Gray: “Yes, it’s strange, I know. I shouldn’t feel sorry for him, but I do.”

Of course we should never forget how cruel these crimes can be, nor how damaging and unfair for their victims. We might find ourselves wishing that criminals, even those as interesting as Sgarbi, would disappear, that crime itself might cease. But that of course is impossible. Wrongdoing is baked into the human condition. And we wouldn’t quite want that anyway, would we? What would writers like Kevin Gray and Charles Bowden and David Grann do with themselves?

On the other hand: if crime disappeared entirely, there would probably be even more crime shows on TV to employ them.