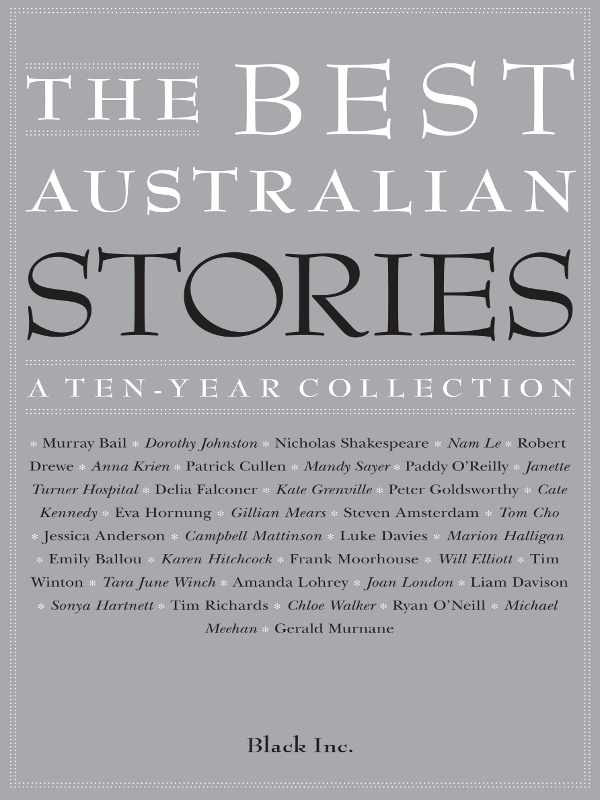

The Best Australian Stories

The Best Australian Stories:

A Ten-Year Collection

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

37â39 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email: [email protected]

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Introduction & this collection © Black Inc., 2011.

Individual stories © retained by the authors.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

e-ISBN: 9781921870163

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of material in this book. However, where an omission has occurred, the publisher will gladly include acknowledgement in any future edition.

Contents

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

Murray Bail

Dorothy Johnston

Nicholas Shakespeare

Nam Le

Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice

Robert Drewe

Anna Krien

Patrick Cullen

Mandy Sayer

Paddy O'Reilly

Janette Turner Hospital

Delia Falconer

Kate Grenville

Peter Goldsworthy

Cate Kennedy

Eva Hornung

Gillian Mears

Steven Amsterdam

Tom Cho

Jessica Anderson

Campbell Mattinson

Luke Davies

Marion Halligan

Emily Ballou

Karen Hitchcock

Frank Moorhouse

Will Elliott

Tim Winton

Tara June Winch

Amanda Lohrey

Joan London

Liam Davison

Sonya Hartnett

Tim Richards

Chloe Walker

Ryan O'Neill

Michael Meehan

Gerald Murnane

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

This book selects the best stories of the past decade, as have appeared in the

Best Australian Stories

annuals.

It draws on the work of five esteemed editors â Peter Craven, Frank Moorhouse, Robert Drewe, Delia Falconer and Cate Kennedy â who read their way through countless stories in search of each year's very best.

The book you hold in your hands takes their careful work and refines it yet further. Our aim has been to produce a book of uniform quality but great variety, showcasing the vigour and diversity of Australian short fiction.

The

Best Stories

series was born over ten years ago when, inspired by the

Best American Stories

, Black Inc.'s founder, Morry Schwartz, thought to launch an Australian equivalent. Since then, the short story has undergone a remarkable revival in Australia; where once it was neglected as the novel's less-glamorous cousin, it is now receiving the respect and attention it deserves. Some of the most exciting new writers of recent years have devoted themselves to the shorter form. We are pleased and proud to feature many of them in this volume.

We hope that this book distils a decade of great Australian writing and sets a new benchmark for the short story in this country.

Black Inc.

Murray Bail

All things considered, piano-tuning is a harmless profession. Working by themselves in rooms filled with other people's most intimate belongings, piano-tuners give the impression of wanting to be somewhere else. They're known to jump at unexpected sounds. At the sight of blood they'd run a mile. And yet early in 1943 Eric Banerjee, along with some other able-bodied men, was called up by the army to defend his country. âMr Banerjee wouldn't hurt a fly' â that came from a widow who lived alone in the Adelaide foothills, where her Beale piano kept going out of tune.

It followed that, if a man as harmless as Eric Banerjee had been called up, the situation to the north was far more serious than the authorities were letting on.

For the piano-tuner it could not have come at a worse time. He had a wife, whose name was Lina, and a daughter who was just beginning to talk. It had taken him years to build up a client base, which barely gave them enough to live on. Then almost overnight â when the war broke out â there was a simultaneous lifting of piano lids across the suburbs of Adelaide, and suddenly Banerjee found he couldn't keep up with demand. These were solid inquiries from piano owners he had never heard of before, in suburbs such as Norwood and St Peters, even as far away as Hackney. In times of uncertainty people turn for consolation to music. Apparently the same thing happened in London, Berlin, Leningrad.

âI'd say it was some sort of clerical mistake.' He patted his wife on the shoulder. âI won't be gone for long.' She'd burst into hysterical sobbing. What would happen now to her and their baby daughter?

Already the city was half empty. Every day the newpapers carried grainy photographs of another explosion or oil refinery in flames, another ship going down and, if that wasn't alarming enough, maps of Burma and Singapore which had thick black arrows sprouting from the Japanese army, all curving south in an accelerating mass, not only towards Australia basking in the Pacific, but heading for Adelaide, its streets wide open, defenceless. And now it was as if he, and he alone, had been selected to single-handedly stand in front and stop the advancing horde.

This uncertainty and the vague fear that he might be killed gradually gave way to a curiosity at leaving home and his wife and child, although he was bound in strong intimacy to them, and entering â embarking upon â a series of situations on a large scale, in the company of other men.

Besides, there was little he could do. The immediate future was out of his hands; he could feel himself carried along by altogether larger forces, a small body in a larger mass, which was a pleasant feeling too.

*

Eric Banerjee gave his date of birth and next of kin, and was examined by a doctor. Later he was handed a small piece of paper to exchange for a uniform the colour of fresh cow manure, and a pair of stiff black boots with leather laces. At home he put the uniform on again and gave his wife in the kitchen a snappy salute.

It was so unusual she began shouting. âAnd now look what you've done!' Their daughter was pointing at him, screwing up her face, and crying.

On the last morning Banerjee finished shaving and looked at himself in the mirror.

He tried to imagine what other people would make of his face, especially the many different strangers he was about to meet. In the mirror he couldn't get a clear impression of himself. He tried an earnest look, a canny one, then out-and-out gloom and pessimism, all with the help of the uniform. He didn't bother trying to look fierce. For a moment he wondered how he looked to others â older or younger? He then returned to normal, or what appeared to be normal â he still seemed to be pulling faces.

âI'll be off then,' he said to Lina. âI can't exactly say, of course, when I'll be back.'

He heard his voice, solemn and stiff, as if these were to be the last words to his wife.

âYou're not even sorry you're going,' she had cried the night before.

Now at the moment of departure something already felt missing. At the same time, everything around him â including himself â felt too ordinary. Surely at a moment like this everything should have been different. Turning, he kept giving little waves with his pianist's fingers. Already he was almost having a good time.

*

At the barracks he was told to stand to attention out in the sun with some other men. Later there was a second, more leisurely inspection where he had to stand in a line, naked. Then an exceptionally thin officer seated at a trestle table, whom Banerjee recognised as his local bank manager, asked some brief questions.

Banerjee's qualifications were not impressive. The officer sighed, as if the war was now well and truly lost, and taking a match winced as he dug around inside his ear. With some disappointment Banerjee thought he might be let off â sent home. But the officer reached for a rubber stamp. Because of his occupation, âpiano-tuner', Banerjee was placed with a small group in the shade, to one side. These were artists, as well as a lecturer in English who sat on the ground clasping his knees, a picture-framer, a librarian as deaf as a post, a signwriter who did shop windows, and others too overweight or too something to hold a rifle.

Over the next few days they marched backwards and forwards, working on drill. They were shown how to look after equipment and when to salute. Nothing much more.

A week had barely gone by when the order came to report to the railway station, immediately. It was late afternoon. Lugging their gear they sauntered behind a silver-haired man who appeared to be a leader. As Banerjee hummed a tune he wondered if they should have been in step. From a passing truck soldiers whistled and laughed at them.

âI don't have a clue where we're heading.'

âSearch me,' said the signwriter.

Banerjee took a cigarette offered, though he never really smoked.

*

Every seat was taken with soldiers. Most were young, barely twenty, but actually looked like soldiers. Tanned, tired-looking faces in worn uniforms. They played cards or sprawled about in greatcoats. A few gazed out the window, even after it was dark. A few tried writing letters. Some shouted out in their sleep. The motion of the long train and the absence of a known destination gave the impression they were travelling endlessly, while at the same time remaining in the one spot. To Banerjee, the feeling of leaving an old life and heading towards a new unknown life became blurry. A voice asked, âWhat day are we?' Later another, âHas anyone got the time?'