The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald (37 page)

Read The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald Online

Authors: F. Scott Fitzgerald

Tags: #Fiction

FROM

METROPOLITAN

MAGAZINE,

JUNE 1922

EULOGY ON THE FLAPPER

By Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald

The Flapper is deceased. Her outer accoutrements have been bequeathed to several hundred girls’ schools throughout the country, to several thousand big-town shop-girls, always imitative of the several hundred girls’ schools, and to several million small-town belles always imitative of the big-town shop-girls via the “novelty stores” of their respective small towns. It is a great bereavement to me, thinking as I do that there will never be another product of circumstance to take the place of the dear departed.

I am assuming that the Flapper will live by her accomplishments and not by her Flapping. How can a girl say again, “I do not want to be respectable because respectable girls are not attractive,” and how can she again so wisely arrive at the knowledge that “boys

do

dance most with the girls they kiss most,” and that “men

will

marry the girls they could kiss before they had asked papa?” Perceiving these things, the Flapper awoke from her lethargy of subdeb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart. She had mostly masculine friends, but youth does not need friends—it needs only crowds, and the more masculine the crowds the more crowded for the Flapper. Of these things the Flapper was well aware!

Now audacity and earrings and one-piece bathing suits have become fashionable and the first Flappers are so secure in their positions that their attitude toward themselves is scarcely distinguishable from that of their débutante sisters of ten years ago toward

themselves.

They have won their case. They are blasé. And the new Flappers galumping along in unfastened galoshes are striving not to do what is pleasant and what they please, but simply to outdo the founders of the Honorable Order of Flappers; to outdo

everything.

Flapperdom has become a game; it is no longer a philosophy.

I came across an amazing editorial a short time ago. It fixed the blame for all divorces, crime waves, high prices, unjust taxes, violations of the Volstead Act and crimes in Hollywood upon the head of the Flapper. The paper wanted back the dear old fireside of long ago, wanted to resuscitate “Hearts and Flowers” and have it instituted as the sole tune played at dances from now on and forever, wanted prayers before breakfast on Sunday morning—and to bring things back to this superb state it advocated restraining the Flapper. All neurotic “women of thirty” and all divorce cases, according to the paper, could be traced to the Flapper. As a matter of fact, she hasn’t yet been given a chance. I know of no divorcées or neurotic women of thirty who were ever Flappers. Do you? And I should think that fully airing the desire for unadulterated gaiety, for romances that she knows will not last, and for dramatizing herself would make her more inclined to favor the “back to the fireside” movement than if she were repressed until age gives her those rights that only youth has the right to give.

I refer to the right to experiment with herself as a transient, poignant figure who will be dead tomorrow. Women, despite the fact that nine out of ten of them go through life with a death-bed air either of snatching-the-last-moment or with martyr-resignation, do not die tomorrow—or the next day. They have to live on to any one of many bitter ends, and I should think the sooner they learned that things weren’t going to be over until they were too tired to care, the quicker the divorce court’s popularity would decline.

“Out with inhibitions,” gleefully shouts the Flapper, and elopes with the Arrow-collar boy that she had been thinking, for a week or two, might make a charming breakfast companion. The marriage is annulled by the proverbial irate parent and the Flapper comes home, none the worse for wear, to marry, years later, and live happily ever afterwards.

I see no logical reasons for keeping the young illusioned. Certainly disillusionment comes easier at twenty than at forty—the fundamental and inevitable disillusionments, I mean. Its effects on the Flappers I have known have simply been to crystallize their ambitious desires and give form to their code of living so that they

can

come home and live happily ever afterwards—or go into the movies or become social service “workers” or something. Older people, except a few geniuses, artistic and financial, simply throw up their hands, heave a great many heart-rending sighs and moan to themselves something about what a hard thing life is—and then, of course, turn to their children and wonder why they don’t believe in Santa Claus and the kindness of their fellow men and in the tale that they will be happy if they are good and obedient. And yet the strongest cry against Flapperdom is that it is making the youth of the country cynical. It is making them intelligent and teaching them to capitalize their natural resources and get their money’s worth. They are merely applying business methods to being young.

“Don’t treat me like a girl,” she warned him, “I’m not like any girl YOU ever saw.”

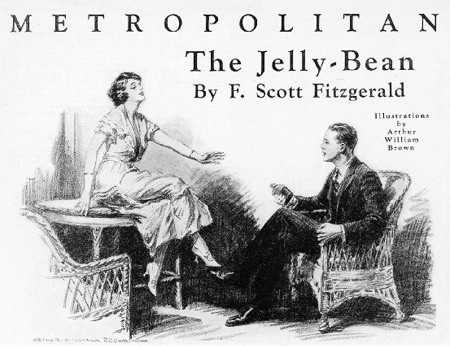

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story “The Jelly-Bean,” illustrated by Arthur William Brown, was published in

Metropolitan

magazine, October 1920.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Joan M.

Candles and Carnival Lights: The Catholic Sensibility of F. Scott

Fitzgerald.

New York: New York University Press, 1978.

Bruccoli, Matthew J.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Descriptive Bibliography.

Revised edition. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1987.

———.

Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981.

———, ed., with the assistance of Jennifer McCabe Atkinson.

As Ever, Scott

Fitz—: Letters Between F. Scott Fitzgerald and His Literary Agent, Harold Ober,

1919–1940.

Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1972.

——— and Jackson R. Bryer, eds.

F. Scott Fitzgerald in His Own Time: A Miscellany.

Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1971.

——— and Margaret M. Duggan, eds., with the assistance of Susan Walker.

Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

New York: Random House, 1980.

———, Scottie Fitzgerald Smith, and Joan P. Kerr, eds. The Romantic Egoists: A

Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974.

Bryer, Jackson R.

The Critical Reputation of F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Bibliographical

Study.

Hamden, CT: Archon, 1967.

———.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Critical Reception.

New York: Burt Franklin, 1978.

———, ed.

New Essays on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Neglected Stories.

Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996.

———, ed.

The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald: New Approaches to Criticism.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982.

———, Alan Margolies, and Ruth Prigozy, eds.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: New Perspectives.

Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Ledger: A Facsimile. Washington, D.C.: NCR/Microcard Editions, 1972.

———.

All the Sad Young Men.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926.

———.

The Crack-Up.

Ed. Edmund Wilson. New York: New Directions, 1945.

———.

Flappers and Philosophers.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

———.

The Great Gatsby.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

———.

Tales of the Jazz Age.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922.

———.

This Side of Paradise.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

Fryer, Sarah Beebe.

Fitzgerald’s New Women: Harbingers of Change.

Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1988.

Higgins, John A.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Study of the Stories.

Jamaica, NY: St. John’s University Press, 1971.

Kuehl, John.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Study of the Short Fiction.

Boston: Twayne, 1991.

———, ed.

The Apprentice Fiction of F. Scott Fitzgerald: 1909–1917.

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1965.

———, and Jackson R. Bryer, eds.

Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins

Correspondence.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971.

Mangum, Bryant.

A Fortune Yet: Money in the Art of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Stories.

New York: Garland, 1991.

Milford, Nancy.

Zelda: A Biography.

New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

Mizener, Arthur.

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951.

Petry, Alice Hall.

Fitzgerald’s Craft of Short Fiction: The Collected Stories—

1920–1935.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989.

Piper, Henry Dan.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Critical Portrait.

New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965.

Prigozy, Ruth, ed.

The Cambridge Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

West, James L. W., III. The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King, His First Love. New York: Random House, 2005.

———, ed.

Flappers and Philosophers.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

———, ed.

Tales of the Jazz Age.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Wilson, Edmund, ed.

The Crack-Up.

New York: New Directions, 1945.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank Judy Sternlight at Random House, who first suggested this project to me and who has guided it from beginning to end. I am also grateful to Vincent La Scala for his extraordinary vigilance, to Gabrielle Bordwin for a cover design that catches so many of the words in these stories in a single image, and to Allison Merrill for her sharp reader’s eye. My graduate and undergraduate Fitzgerald seminar members at Virginia Commonwealth University have provided useful suggestions during the preparation of this volume, and I am grateful to them. Thanks also to Matthew J. Bruccoli of the University of South Carolina for his ongoing support; to Rebecca M. Dale for her research assistance; and to James L. W. West III of Pennsylvania State University for his helpful advice to me on this project. Finally, thanks to Rebecca Angus Mangum for her patience and her support during the preparation of this volume.

READING GROUP GUIDE

In

This Side of Paradise,

written before any of the stories in this volume, Amory Blaine describes the generation coming of age in the early 1920s as a generation “grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” The main characters in these early Fitzgerald stories are part of this generation. To what degree are their actions and their codes of behavior—from the early flappers to the later sad young men— dictated by the moral complexity that comes with growing up in an age when the conventional wisdom of their elders no longer prevails? To what degree does gender play a role in their development of a system of values to live by?

The young women in these stories all seem to value individual freedom and independence, from the youngest like Bernice and Marjorie in “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” to the most seasoned like Ardita Farnam in “The Offshore Pirate.” But as Zelda Fitzgerald remarked in “Eulogy on the Flapper,” the flapper eventually “comes home, none the worse for wear, to marry, years later, and live happily ever afterwards.” In light of the fact that most of the young women in these stories either wind up married or headed in the direction of matrimony, do their professed beliefs in individual freedom seem illusionary or, at worst, disingenuous? For the young women in these stories, what is the relationship between individual liberty and economic freedom?

When Anton Laurier comes to the home of Horace and Marcia in “Head and Shoulders,” Horace makes this remark to him: “About raps. Don’t answer them! Let them alone—have a padded door.” Do you think Fitzgerald wrote this clever line for Horace simply to end the story on a light note? Or could it have deeper implications that reflect Horace’s true feelings about the course his life has taken after meeting Marcia? Could there be deeper biographical implications of this remark in light of the fact that Fitzgerald was about to embark on a life with Zelda? Discuss.

There is wide disagreement over the artistic value of “Benediction”—more so than any other story in this collection—particularly over whether it earns what some consider its “O. Henry” ending. There is also considerable debate among critics as to what Lois plans to do in the future. What do you think the torn up and discarded telegram left in the wastebasket suggests that Lois plans to do next? And do you think the story “earns” its ending? What is the connection between the story’s conclusion and what happens to Lois during the Benediction ceremony earlier in the story?

Fitzgerald maintained that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” Throughout his fiction, he does seem able to appreciate the superficial attractiveness of the world he is also criticizing. “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” originated in a detailed letter Fitzgerald wrote to his sister advising her as to how she could make herself more acceptable to a society that is very much like the society Marjorie is grooming Bernice to enter. Does Fitzgerald appear to value, even to glorify, the exclusive society depicted in the story? If so, how do you reconcile this with Bernice’s dramatic act at the conclusion of the narrative? What could account for what might be called Fitzgerald’s “double vision,” not only in this story, but also in many of the stories in this collection? How are his themes strengthened or weakened by his double vision?

“The Diamond as Big as the Ritz” seems like an indictment of the capitalistic system that has produced individuals like Braddock Washington, who would rather blow up his diamond mountain and kill himself in the process than have the diamond market ruined through its discovery by the government. To what degree is the story, with its references to Hades and the twelve men of Fish, allegorical? How do you reconcile your ideas about its allegorical meaning with Fitzgerald’s contention that he wrote the story “utterly for my own amusement”?

Dexter Green is one of Fitzgerald’s saddest young men at the end of “Winter Dreams.” The catalyst for his sadness is Devlin’s revelation about what has become of Judy Jones. Is it finally Dexter’s loss of Judy Jones herself that brings him to the edge of despair, causing him to contemplate “the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time,” or is it some deeper thing she symbolizes? In either case, why do you think Dexter is devastated to learn what he learns from Devlin about Judy?

In the story “Absolution,” Carl Miller’s “two bonds with the colorful life were his faith in the Roman Catholic Church and his mystical worship of the Empire Builder, James J. Hill.” Given what lies “[o]utside the window” in the last paragraph of the story, what is Rudolph’s bond with the “colorful life” likely to be? Is it easy or difficult to imagine Rudolph, like Jay in

The

Great Gatsby,

earning a fortune and wedding his visions to the “perishable breath” of a spoiled rich girl like Daisy Fay Buchanan?