The Betrayal of Maggie Blair

Read The Betrayal of Maggie Blair Online

Authors: Elizabeth Laird

Elizabeth Laird

Table of Contents

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Boston New York 2011

First U.S. Edition

Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth Laird

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Macmillan Children's Books,

a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin

Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York,

New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Publishing Company.

The text of this book is set in Adobe Garamond.

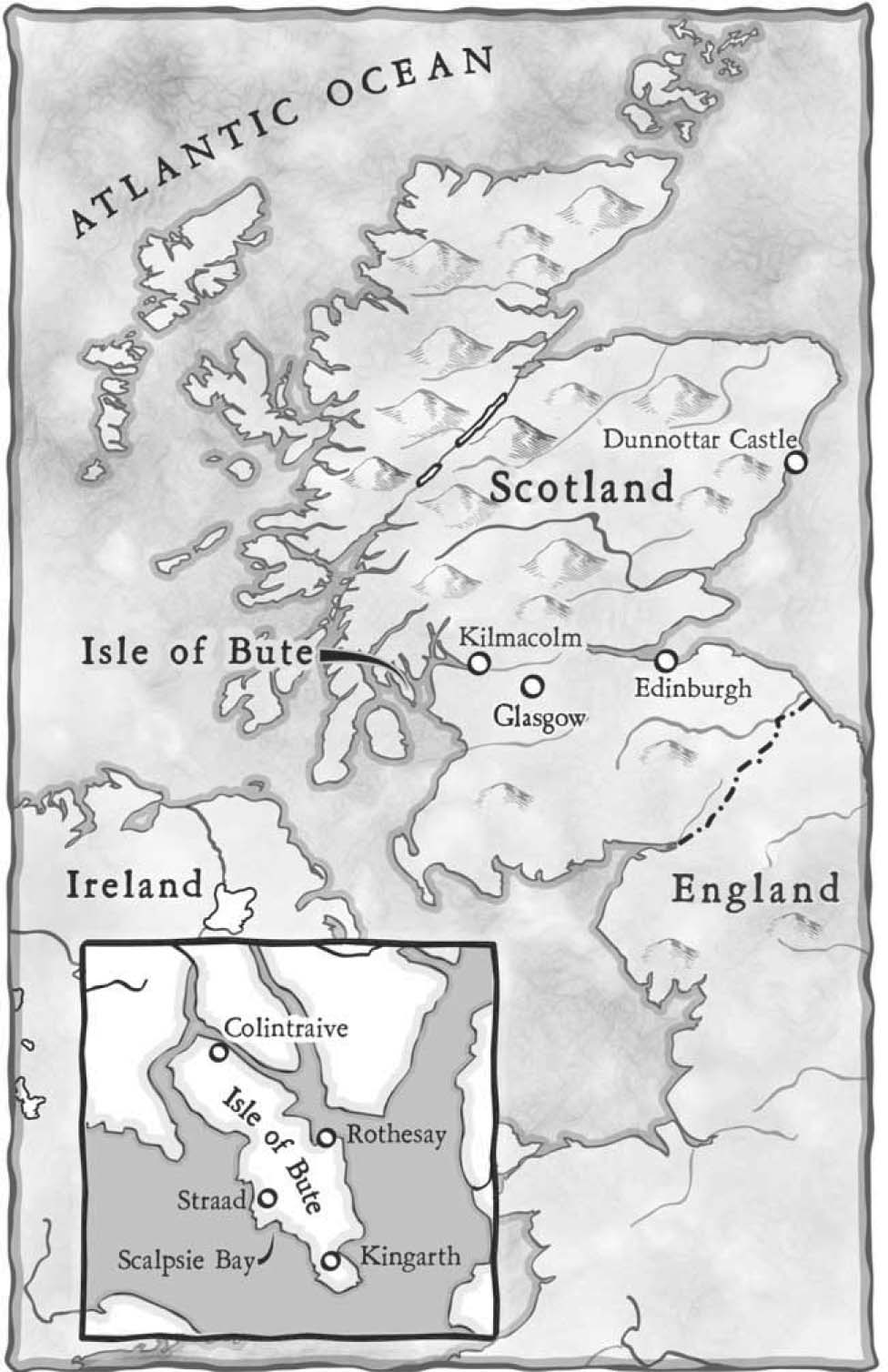

Map art by Joe LeMonnier

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Laird, Elizabeth.

The betrayal of Maggie Blair / by Elizabeth Laird.

p. cm.

Summary: In seventeenth-century Scotland, sixteen-year-old Maggie

Blair is sentenced to be hanged as a witch but escapes to the home of her

uncle, placing him and his family in great danger as she risks her life to

save them all from the King's men.

ISBN 978-0-547-34126-2

[1. WitchcraftâFiction. 2. Fugitives from justiceâFiction.

3. UnclesâFiction. 4. Bet rayalâFiction. 5. Scot landâHistoryâ

17th centuryâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.L1579Bft 2011

[Fic]âdc22

2010025120

Manufactured in the United States

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For the Laird Family

I would like to thank

Alistair Laird McGeachy, who first told me about Hugh

Blair, our mutual ancestorThe Riis family, who welcomed me to Ladymuir

My husband David McDowall, who inspired me with his

enthusiasm for the Isle of ButeLindsey Fraser for her interest and encouragement,

and, as ever, Jane Fior for her invaluable help

and guidance

I was the first one to see the dead whale lying on the sand at Scalpsie Bay. It must have been washed up in the night. I could imagine it flopping out of the sea, thrashing its tail, and opening and shutting the cavern of its mouth. It was huge and shapeless, a horrible dead thing, and it looked as if it would feel slimy if you dared to touch it. I crept up to it cautiously. There were monsters in the deep, I knew, and a great one, the Leviathan, which the Lord had made to be the terror of fishermen. Was this one of them? Would it come to life and devour me?

The sand was ridged into ripples by the outgoing tide, which had left the usual orange lines of seaweed and bright white stripes of shells. The tide had also scooped out little pools around the dead beast's sides, and crabs were already scuttling there, as curious as I was.

It was a cold day in December. The sun had barely risen, and I'd pulled my shawl tightly around my head and shoulders. But it wasn't only the chill of the wet sand beneath my bare feet that made me shiver. There was a strangeness in the air.

Across the water I could already make out the Isle of Arran, rearing up out of the sea, the tops of its mountains hidden as usual in a crown of clouds. I'd seen Arran a dozen times a day, every day of my life, each time I'd stepped out the door of my grandmother's cottage. I knew it so well that I hardly ever noticed it.

But today as I looked up at the mountains from the dead whale in front of me, the island seemed to shift, and for a moment I thought it was moving toward me, creeping across the water. It was coming for me, wanting to swallow me up, along with the beach and Granny's cottage, Scalpsie Bay, and the whole of the Isle of Bute.

And then beyond Arran, out there in the sea, a shaft of sunlight pierced through the clouds and laid a golden path across the gray water, tingeing the dead whale with brilliant light. The clouds were dazzled with glory, and I was struck with a terror so great that my legs stiffened and I couldn't move.

"It's the Lord Jesus," I whispered. "He's coming now, to judge the living and the dead."

I waited, my hands clamped in a petrified clasp, expecting to see Christ walk down the sunbeam and across the water, angels flying on gleaming wings around him. The minister had said there would be trumpets as the saved rose up in the air like flocks of giant birds to meet the Lord, but down here on the ground there would be wailing and gnashing of teeth as the damned were sucked into Hell by the Evil One.

"Am I saved, Lord Jesus? Will you take me?" I cried out loud. "And Granny too?"

The clouds were moving farther apart, and the golden path was widening, making the white crests on the little waves sparkle like the clothes of the Seraphim.

I was certain of it then. I wasn't one of the Chosen to rise with Jesus in glory. I was one of the damned, and Granny was too.

"No!" I shrieked. "Not yet! Give me another chance, Lord Jesus!"

And then I must have fallen down because the next thing I remember was Granny saying, "She's taken a fit, the silly wee thing. Pick her up, won't you?"

I was only half conscious again, but I knew it was Mr. Macbean's rough hands painfully holding my arms and the gruff voice of Samuel Kirby complaining as he held my legs.

"What are you doing, you dafties?" Granny shouted in the rough, angry voice I dreaded. "Letting her head fall back like that! Trying to break her neck, are you? Think she's a sack of oatmeal?"

Behind me, above the crunch of many feet following us up the beach toward our cottage, I could hear anxious murmurs.

"The creature's the size of a kirk! And the tail on it, did you see? It'll stink when it rots. Infect the air for weeks, so it will."

And the sniping tongues were busy as usual.

"Hark at Elspeth! Shouting like that. Evil old woman. Why does she want to be so sharp? They should drop the girl and let the old body carry her home herself."

Then came the sound of our own door creaking back on its leather hinge, the smell of peat smoke, and the soft tail of Sheba the cat brushing against my dangling hand.

They dropped me down on the pile of straw in the corner that I used as a bed, and a moment later Granny had shooed them out of the cottage. I was quite back in my wits by then, and I started to sit up.

"Stay there," commanded Granny.

She was standing over me, frowning as she stared at me. Her mouth was pulled down hard at the corners, and the stiff black hairs on her chin were quivering. They were sharp, those bristles, but not as sharp as the bristles in her soul.

"Now then, Maggie. What was all that for? Why did you faint? What did you see?"

"Nothing, Granny. The whale..."

She shook her head impatiently.

"Never mind the whale. While you were away, in the faint. Was there a vision?"

"No. I justâeverything was black. Before that I thought I sawâ"

"What? What did you see? Do I have to pull it out of you?"

"The sky looked strange, and there was the whaleâ it scared meâand I thought that Jesus was coming. Down from the sky. I thought it was the Last Day."

She stared at me a moment longer. There wasn't much light in the cottage, only a square of brightness that came through the open door and a faint glow from the peat burning in the middle of the room, but I could see her eyes glittering.

"The whale's an omen. It means no good. It didn't speak to you?"

"No! It was dead. I thought the Lord Jesus was coming, that's all."

"Hmph." She turned away and pulled on the chain that hung from the rafter, holding the cauldron in place over the fire. "That's nothing but kirk talk. You're a disappointment to me, Maggie. Your mother had it, the gift of far-seeing, but you've nothing more in your head than what's been put there by the minister. You're your father all over again, stubborn and blind and selfish. My Mary gave you nothing of herself at all. If I hadn't delivered you into this world with my own hands, I'd have thought you were changed at birth."

Granny knew where to plunge her dagger and twist it for good measure. There was no point in answering her. I bit my lip, stood up, and shook the straws off the rough wool of my skirt.

"Shall I milk Blackie now?"

"After you've touched a dead whale? You'll pass on the bad luck and dry her milk up for good. You're more trouble than you're worth, Maggie. Always were, always will be."

"I didn't touch the whale. I only..."

She raised a hand and I ducked.

"Get away up the hill and cut a sack of peat. The stack's low already, or had you been too full of yourself to notice?"

Cutting peat and lugging it home was the hardest work of all, and usually I hated it, but today, in spite of the rain that was now sweeping in from the sea, I was glad to get out of the cottage and run away to the glen. I usually went the long way, up the firm path that went around and about before it reached the peat cuttings, but today I plunged straight on through the bog, trampling furiously through the mass of reeds and flags and the treacherous bright grass that hid the pools of water, not hearing the suck of the mud as I pulled my feet out, not feeling the wetness that seeped up the bottom of my gown, not even noticing the scratches from the prickly gorse as it tore at my arms.

"An evil old woman. They were right down there. That's what you are." Away from Granny, I felt brave enough to answer back. "I

am

like my mam. I've her hair, and her eyes, and her smile, so Tam says."

Most people called old Tam a rogue, a thief, a lying, drunken rascal, living in his tumbledown shack like a pig in a sty. But he was none of those things to me. He'd known my mother, and I knew he'd never lie about her to me.

I don't remember my mother. She was Granny's only child, and she died of a fever when I was a very little girl. I just about remember my father. He was a big man, not given to talking much. He was a rover by nature, Tam said. He came to the Isle of Bute from the mainland to fetch the Laird of Keames's cattle and drive them east across the hills to sell in Glasgow. He was only meant to stay in Bute for a week or two, while the cattle were rounded up for him, but he chanced on my mother as she walked down the lane to the field to milk Blackie one warm June evening. The honeysuckle was in flower and the wild roses too, and it was all over with him at once, so Tam said.

"Never a love like it, Maidie," Tam told me. "Don't you listen to your granny. A child born of love you are, given to love, made for love."

"Granny said the sea took my father," I asked Tam once. "What did she mean?"

I'd imagined a great wave curling up the beach, twining around my father's legs, and sucking him back into the depths.

"An accident, Maidie. Nothing more." Tam heaved a sigh. "Your father was taking the cattle to the mainland up by Colintraive, making them swim across the narrows there. He'd done it a dozen times before. The beasts weren't easyâlively young steers they wereâand one of them was thrashing about in the water as if a demon possessed it. Perhaps a demon did, for the steer caught your father on the head with its horn, and it went right through his temple. He went down under the water, and when he was washed up a week later, there was a wound from his eyebrow to the line of his hair deep enough to put your hand inside."

***

There's nothing like hard work in the cold of a wet December day for cooling your temper, and by the time I got home I was more miserable than angry. My arms were aching from the weight of the sack. I was wet through. The mud on my hem slapped clammily against my ankles, and I wished I'd been sensible instead of running through the bog.

I was expecting another scolding from Granny as soon as she saw the state of my clothes, the rips in my shawl, and my face all streaked with peat and rain and tears, but she only said, "Oh, so it's you come home again, and a fine sight you are too. Running through the bog like a mad childâ

I

saw you."

She took my wooden bowl down from the shelf, ladled some hot porridge into it from the cauldron, and put it into my hands.

"Take off that soaking shawl and put it to dry, and your gown too."