The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (27 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

10.1Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In the interval between the onset of the sexual revolution of the early 1960s and the rise of feminism in the 1970s, the control of women’s sexuality was seen as a perquisite of sophisticated men. Boasts of sexual coercion and jealous violence appeared in popular novels and films and in the lyrics of rock songs such as the Beatles’ “Run for Your Life

,

” Neil Young’s “Down by the River

,

” Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe

,

” and Ronnie Hawkins’s “Who Do You Love?”

121

It was even rationalized in “revolutionary” political writings, such as Eldridge Cleaver’s bestselling 1968 memoir

Soul on Ice

, in which the Black Panther leader wrote:

,

” Neil Young’s “Down by the River

,

” Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe

,

” and Ronnie Hawkins’s “Who Do You Love?”

121

It was even rationalized in “revolutionary” political writings, such as Eldridge Cleaver’s bestselling 1968 memoir

Soul on Ice

, in which the Black Panther leader wrote:

Rape was an insurrectionary act. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the white man’s law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women—and this point, I believe, was the most satisfying to me because I was very resentful over the historical fact of how the white man has used the black woman. I felt I was getting revenge.

122

Somehow the interests of the women who were defiled in this insurrectionary act never figured into his political principles, nor into the critical reaction to the book (

New York Times

: “Brilliant and revealing”;

The Nation:

“A remarkable book . . . beautifully written”;

Atlantic Monthly:

“An intelligent and turbulent and passionate and eloquent man”).

123

New York Times

: “Brilliant and revealing”;

The Nation:

“A remarkable book . . . beautifully written”;

Atlantic Monthly:

“An intelligent and turbulent and passionate and eloquent man”).

123

As the rationalizations for criminality caught the attention of judges and legislators, they became increasingly reluctant to put miscreants behind bars. Though the civil liberties reform of the era did not lead to nearly as many vicious criminals “going free on a technicality” as the

Dirty Harry

movies would suggest, law enforcement was indeed retreating as the crime rate was advancing. In the United States from 1962 to 1979, the likelihood that a crime would lead to an arrest dropped from 0.32 to 0.18, the likelihood that an arrest would lead to imprisonment dropped from 0.32 to 0.14, and the likelihood that a crime would lead to imprisonment fell from 0.10 to 0.02, a factor of five.

124

Dirty Harry

movies would suggest, law enforcement was indeed retreating as the crime rate was advancing. In the United States from 1962 to 1979, the likelihood that a crime would lead to an arrest dropped from 0.32 to 0.18, the likelihood that an arrest would lead to imprisonment dropped from 0.32 to 0.14, and the likelihood that a crime would lead to imprisonment fell from 0.10 to 0.02, a factor of five.

124

Even more calamitous than the return of hoodlums to the street was the mutual disengagement between law enforcement and communities, and the resulting deterioration of neighborhood life. Offenses against civil order like vagrancy, loitering, and panhandling were decriminalized, and minor crimes like vandalism, graffiti-spraying, turnstile-jumping, and urinating in public fell off the police radar screens.

125

Thanks to intermittently effective antipsychotic drugs and a change in attitudes toward deviance, the wards of mental hospitals were emptied, which multiplied the ranks of the homeless. Shopkeepers and citizens with a stake in the neighborhood, who otherwise would have kept an eye out for local misbehavior, eventually surrendered to the vandals, panhandlers, and muggers and retreated to the suburbs.

125

Thanks to intermittently effective antipsychotic drugs and a change in attitudes toward deviance, the wards of mental hospitals were emptied, which multiplied the ranks of the homeless. Shopkeepers and citizens with a stake in the neighborhood, who otherwise would have kept an eye out for local misbehavior, eventually surrendered to the vandals, panhandlers, and muggers and retreated to the suburbs.

The 1960s decivilizing process affected the choices of individuals as well as policymakers. Many young men decided that they ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more and, instead of pursuing a respectable family life, hung out in all-male packs that spawned the familiar cycle of competition for dominance, insult or minor aggression, and violent retaliation. The sexual revolution, which provided men with plentiful sexual opportunities without the responsibilities of marriage, added to this dubious freedom. Some men tried to get a piece of the lucrative trade in contraband drugs, in which self-help justice is the only way to enforce property rights. (The cutthroat market in crack cocaine in the late 1980s had a particularly low barrier for entry because doses of the drug could be sold in small amounts, and the resulting infusion of teenage crack dealers probably contributed to the 25 percent increase in the homicide rate between 1985 and 1991.) On top of the violence that accompanies any market in contraband, the drugs themselves, together with good old-fashioned alcohol, lowered inhibitions and sent sparks onto the tinder.

The decivilizing effects hit African American communities particularly hard. They started out with the historical disadvantages of second-class citizenship, which left many young people teetering between respectable and underclass lifestyles just when the new antiestablishment forces were pushing in the wrong direction. They could count on even less protection from the criminal justice system than white Americans because of the combination of old racism among the police and the new indulgence by the judicial system toward crime, of which they were disproportionately the victims.

126

Mistrust of the criminal justice system turned into cynicism and sometimes paranoia, making self-help justice seem the only alternative.

127

126

Mistrust of the criminal justice system turned into cynicism and sometimes paranoia, making self-help justice seem the only alternative.

127

On top of these strikes came a feature of African American family life first pointed out by the sociologist Daniel Patrick Moynihan in his famous 1965 report,

The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,

for which he was initially vilified but eventually vindicated.

128

A large proportion (today a majority) of black children are born out of wedlock, and many grow up without fathers. This trend, already visible in the early 1960s, may have been multiplied by the sexual revolution and yet again by perverse welfare incentives that encouraged young women to “marry the state” instead of the fathers of their children.

129

Though I am skeptical of theories of parental influence that say that fatherless boys grow up violent because they lack a role model or paternal discipline (Moynihan himself, for example, grew up without a father), widespread fatherlessness can lead to violence for a different reason.

130

All those young men who aren’t bringing up their children are hanging out with one another competing for dominance instead. The mixture was as combustible in the inner city as it had been in the cowboy saloons and mining camps of the Wild West, this time not because there were no women around but because the women lacked the bargaining power to force the men into a civilized lifestyle.

RECIVILIZATION IN THE 1990sThe Negro Family: The Case for National Action,

for which he was initially vilified but eventually vindicated.

128

A large proportion (today a majority) of black children are born out of wedlock, and many grow up without fathers. This trend, already visible in the early 1960s, may have been multiplied by the sexual revolution and yet again by perverse welfare incentives that encouraged young women to “marry the state” instead of the fathers of their children.

129

Though I am skeptical of theories of parental influence that say that fatherless boys grow up violent because they lack a role model or paternal discipline (Moynihan himself, for example, grew up without a father), widespread fatherlessness can lead to violence for a different reason.

130

All those young men who aren’t bringing up their children are hanging out with one another competing for dominance instead. The mixture was as combustible in the inner city as it had been in the cowboy saloons and mining camps of the Wild West, this time not because there were no women around but because the women lacked the bargaining power to force the men into a civilized lifestyle.

It would be a mistake to think of the 1960s crime boom as undoing the decline of violence in the West, or as a sign that historical trends in violence are cyclical, yo-yoing up and down from one era to the next. The annual homicide rate in the United States at its recent worst—10.2 per 100,000 in 1980—was a quarter of the rate for Western Europe in 1450, a tenth of the rate of the traditional Inuit, and a fiftieth of the average rate in nonstate societies (see figure 3–4).

And even that number turned out to be a high-water mark, not a regular occurrence or a sign of things to come. In 1992 a strange thing happened. The homicide rate went down by almost 10 percent from the year before, and it continued to sink for another seven years, hitting 5.7 in 1999, the lowest it had been since 1966.

131

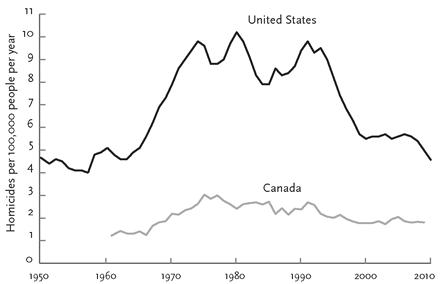

Even more shockingly, the rate stayed put for another seven years and then drooped even further, from 5.7 in 2006 to 4.8 in 2010. The upper line in figure 3–18 plots the American homicide trend since 1950, including the new lowland we have reached in the 21st century.

131

Even more shockingly, the rate stayed put for another seven years and then drooped even further, from 5.7 in 2006 to 4.8 in 2010. The upper line in figure 3–18 plots the American homicide trend since 1950, including the new lowland we have reached in the 21st century.

The graph also shows the trend for Canada since 1961. Canadians kill at less than a third of the rate of Americans, partly because in the 19th century the Mounties got to the western frontier before the settlers and spared them from having to cultivate a violent code of honor. Despite this difference, the ups and downs of the Canadian homicide rate parallel those of their neighbor to the south (with a correlation coefficient between 1961 and 2009 of 0.85), and it sank almost as much in the 1990s: 35 percent, compared to the American decline of 42 percent.

132

132

The parallel trajectory of Canada and the United States is one of many surprises in the great crime decline of the 1990s. The two countries differed in their economic trends and in their policies of criminal justice, yet they enjoyed similar drops in violence. So did most of the countries of Western Europe.

133

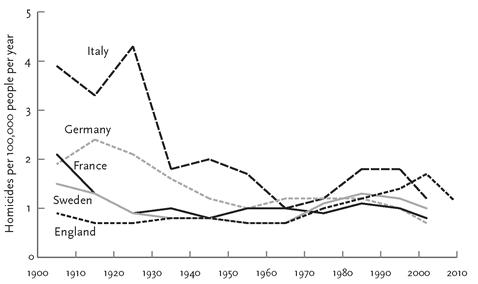

Figure 3–19 plots the homicide rates of five major European countries over the past century, showing the historical trajectory we have been tracking: a long-term decline that lasted until the 1960s, an uptick that began in that tumultuous decade, and the recent return to more peaceable rates. Every major Western European country showed a decline, and though it looked for a while as if England and Ireland would be the exceptions, in the 2000s their rates dropped as well.

133

Figure 3–19 plots the homicide rates of five major European countries over the past century, showing the historical trajectory we have been tracking: a long-term decline that lasted until the 1960s, an uptick that began in that tumultuous decade, and the recent return to more peaceable rates. Every major Western European country showed a decline, and though it looked for a while as if England and Ireland would be the exceptions, in the 2000s their rates dropped as well.

FIGURE 3–18.

Homicide rates in the United States, 1950–2010, and Canada, 1961–2009

Homicide rates in the United States, 1950–2010, and Canada, 1961–2009

Sources:

Data for United States are from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports 1950–2010: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009; U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010b, 2011; Fox & Zawitz, 2007. Data for Canada, 1961–2007: Statistics Canada, 2008. Data for Canada, 2008: Statistics Canada, 2010. Data for Canada, 2009: K. Harris, “Canada’s crime rate falls,”

Toronto Sun

, Jul. 20, 2010.

Data for United States are from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports 1950–2010: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009; U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010b, 2011; Fox & Zawitz, 2007. Data for Canada, 1961–2007: Statistics Canada, 2008. Data for Canada, 2008: Statistics Canada, 2010. Data for Canada, 2009: K. Harris, “Canada’s crime rate falls,”

Toronto Sun

, Jul. 20, 2010.

Not only did people cut down on killing, but they refrained from inflicting other kinds of harm. In the United States the rates of every category of major crime dropped by about half, including rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and even auto theft.

134

The effects were visible not just in the statistics but in the fabric of everyday life. Tourists and young urban professionals recolonized American downtowns, and crime receded as a major issue from presidential campaigns.

134

The effects were visible not just in the statistics but in the fabric of everyday life. Tourists and young urban professionals recolonized American downtowns, and crime receded as a major issue from presidential campaigns.

None of the experts had predicted it. Even as the decline was under way, the standard opinion was that the rise in crime that had begun in the 1960s would even get worse. In a 1995 essay James Q. Wilson wrote:

Just beyond the horizon, there lurks a cloud that the winds will soon bring over us. The population will start getting younger again. By the end of this decade there will be a million more people between the ages of fourteen and seventeen than there are now. This extra million will be half male. Six percent of them will become high-rate, repeat offenders—30,000 more young muggers, killers, and thieves than we have now. Get ready.

135

FIGURE 3–19.

Homicide rates in five Western European countries, 1900–2009

Homicide rates in five Western European countries, 1900–2009

Sources:

Data from Eisner, 2008, except England, 2009, which is from Walker et al., 2009; population estimate from U.K. Office for National Statistics, 2009.

Data from Eisner, 2008, except England, 2009, which is from Walker et al., 2009; population estimate from U.K. Office for National Statistics, 2009.

The cloud beyond the horizon was joined by purple prose from other talking heads on crime. James Alan Fox predicted a “blood bath” by 2005, a crime wave that would “get so bad that it [would] make 1995 look like the good old days.”

136

John DiIulio warned of more than a quarter of a million new “super-predators on the streets” by 2010 who would make “the Bloods and the Crips look tame by comparison.”

137

In 1991 the former editor of the

Times

of London predicted that “by the year 2000, New York could be a Gotham City without Batman.”

138

136

John DiIulio warned of more than a quarter of a million new “super-predators on the streets” by 2010 who would make “the Bloods and the Crips look tame by comparison.”

137

In 1991 the former editor of the

Times

of London predicted that “by the year 2000, New York could be a Gotham City without Batman.”

138

As legendary New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia might have said, “When I make a mistake, it’s a beaut!” (Wilson was a good sport about it, remarking, “Social scientists should never try to predict the future; they have enough trouble predicting the past.”) The mistake of the murder mavens was to have put too much faith in the most recent demographic trends. The crack-fueled violence bubble of the late 1980s involved large numbers of teenagers, and the population of teenagers was set to grow in the 1990s as an echo of the baby boom. But the

overall

crime-prone cohort, which includes twenty-somethings as well as teenagers, actually fell in the 1990s.

139

Even this corrected statistic, though, cannot explain the decline of crime in that decade. The age distribution of a population changes slowly, as each demographic pig makes its way through the population python. But in the 1990s the crime rate lurched downward for seven straight years and promptly parked itself at its new bottom for another nine. As with the takeoff of crime in the 1960s, changes in the

rate

of violence for each age cohort swamped the effect of the

size

of those cohorts.

overall

crime-prone cohort, which includes twenty-somethings as well as teenagers, actually fell in the 1990s.

139

Even this corrected statistic, though, cannot explain the decline of crime in that decade. The age distribution of a population changes slowly, as each demographic pig makes its way through the population python. But in the 1990s the crime rate lurched downward for seven straight years and promptly parked itself at its new bottom for another nine. As with the takeoff of crime in the 1960s, changes in the

rate

of violence for each age cohort swamped the effect of the

size

of those cohorts.

Other books

Crown of Three by J. D. Rinehart

In the End (Starbounders) by Demitria Lunetta

Light from Her Mirror (Mirrors Don't Lie Book 3) by Becki Willis

Veneno de cristal by Donna Leon

Fireside by Brian Parker

A Bit of Rough by Felthouse, Lucy

Happily Ever Addendum by Sadie Grubor, Monica Black

Ghost of a Dream by Simon R. Green

The Sixty-Eight Rooms by Marianne Malone

In Enemy Hands by K.S. Augustin