The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (39 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

3.17Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Still, a gradual shift in sensibilities is often incapable of changing actual practices until the change is implemented by the stroke of a pen. The slave trade, for example, was abolished as a result of moral agitation that persuaded men in power to pass laws and back them up with guns and ships.

124

Blood sports, public hangings, cruel punishments, and debtors’ prisons were also shut down by acts of legislators who had been influenced by moral agitators and the public debates they began.

124

Blood sports, public hangings, cruel punishments, and debtors’ prisons were also shut down by acts of legislators who had been influenced by moral agitators and the public debates they began.

In explaining the Humanitarian Revolution, then, we don’t have to decide between unspoken norms and explicit moral argumentation. Each affects the other. As sensibilities change, thinkers who question a practice are more likely to materialize, and their arguments are more likely to get a hearing and then catch on. The arguments may not only persuade the people who wield the levers of power but infiltrate the culture’s sensibilities by finding their way into barroom and dinner-table debates where they may shift the consensus one mind at a time. And when a practice has vanished from everyday experience because it was outlawed from the top down, it may fall off the menu of live options in people’s imaginations. Just as today smoking in offices and classrooms has passed from commonplace to prohibited to unthinkable, practices like slavery and public hangings, when enough time passed that no one alive could remember them, became so unimaginable that they were no longer brought up for debate.

The most sweeping change in everyday sensibilities left by the Humanitarian Revolution is the reaction to suffering in other living things. People today are far from morally immaculate. They may covet nice objects, fantasize about sex with inappropriate partners, or want to kill someone who has humiliated them in public.

125

But other sinful desires no longer occur to people in the first place. Most people today have no desire to watch a cat burn to death, let alone a man or a woman. In that regard we are different from our ancestors of a few centuries ago, who approved, carried out, and even savored the infliction of unspeakable agony on other living beings. What were these people feeling? And why don’t we feel it today?

125

But other sinful desires no longer occur to people in the first place. Most people today have no desire to watch a cat burn to death, let alone a man or a woman. In that regard we are different from our ancestors of a few centuries ago, who approved, carried out, and even savored the infliction of unspeakable agony on other living beings. What were these people feeling? And why don’t we feel it today?

We won’t be equipped to answer this question until we plunge into the psychology of sadism in chapter 8 and empathy in chapter 9. But for now we can look at some historical changes that militated against the indulgence of cruelty. As always, the challenge is to find an exogenous change that precedes the change in sensibilities and behavior so we can avoid the circularity of saying that people stopped doing cruel things because they got less cruel. What changed in people’s environment that could have set off the Humanitarian Revolution?

The Civilizing Process is one candidate. Recall that Elias suggested that during the transition to modernity people not only exercised more self-control but also cultivated their sense of empathy. They did so not as an exercise in moral improvement but to hone their ability to get inside the heads of bureaucrats and merchants and prosper in a society that increasingly depended on networks of exchange rather than farming and plunder. Certainly the taste for cruelty clashes with the values of a cooperative society: it must be harder to work with your neighbors if you think they might enjoy seeing you disemboweled. And the reduction in personal violence brought about by the Civilizing Process may have lessened the demand for harsh punishments, just as today demands to “get tough on crime” rise and fall with the crime rate.

Lynn Hunt, the historian of human rights, points to another knock-on effect of the Civilizing Process: the refinements in hygiene and manners, such as eating with utensils, having sex in private, and trying to keep one’s effluvia out of view and off one’s clothing. The enhanced decorum, she suggests, contributed to the sense that people are

autonomou

s—that they own their bodies, which have an inherent integrity and are not a possession of society. Bodily integrity was increasingly seen as worthy of respect, as something that may not be breached at the expense of the person for the benefit of society.

autonomou

s—that they own their bodies, which have an inherent integrity and are not a possession of society. Bodily integrity was increasingly seen as worthy of respect, as something that may not be breached at the expense of the person for the benefit of society.

My own sensibilities tend toward the concrete, and I suspect there is a simpler hypothesis about the effect of cleanliness on moral sensibilities: people got less repulsive. Humans have a revulsion to filth and bodily secretions, and just as people today may avoid a homeless person who reeks of feces and urine, people in earlier centuries may have been more callous to their neighbors because those neighbors were more disgusting. Worse, people easily slip from visceral disgust to moralistic disgust and treat unsanitary things as contemptibly defiled and sordid.

126

Scholars of 20th-century atrocities have wondered how brutality can spring up so easily when one group achieves domination over another. The philosopher Jonathan Glover has pointed to a downward spiral of dehumanization. People force a despised minority to live in squalor, which makes them seem animalistic and subhuman, which encourages the dominant group to mistreat them further, which degrades them still further, removing any remaining tug on the oppressors’ conscience.

127

Perhaps this spiral of dehumanization runs the movie of the Civilizing Process backwards. It reverses the historical sweep toward greater cleanliness and dignity that led, over the centuries, to greater respect for people’s well-being.

126

Scholars of 20th-century atrocities have wondered how brutality can spring up so easily when one group achieves domination over another. The philosopher Jonathan Glover has pointed to a downward spiral of dehumanization. People force a despised minority to live in squalor, which makes them seem animalistic and subhuman, which encourages the dominant group to mistreat them further, which degrades them still further, removing any remaining tug on the oppressors’ conscience.

127

Perhaps this spiral of dehumanization runs the movie of the Civilizing Process backwards. It reverses the historical sweep toward greater cleanliness and dignity that led, over the centuries, to greater respect for people’s well-being.

Unfortunately the Civilizing Process and the Humanitarian Revolution don’t line up in time in a way that would suggest that one caused the other. The rise of government and commerce and the plummeting of homicide that propelled the Civilizing Process had been under way for several centuries without anyone much caring about the barbarity of punishments, the power of kings, or the violent suppression of heresy. Indeed as states became more powerful, they also got crueler. The use of torture to extract confessions (rather than to punish), for example, was reintroduced in the Middle Ages when many states revived Roman law.

128

Something else must have accelerated humanitarian sentiments in the 17th and 18th centuries.

128

Something else must have accelerated humanitarian sentiments in the 17th and 18th centuries.

An alternative explanation is that people become more compassionate as their own lives improve. Payne speculates that “when people grow richer, so that they are better fed, healthier, and more comfortable, they come to value their own lives, and the lives of others, more highly.”

129

The hypothesis that life used to be cheap but has become dearer loosely fits within the broad sweep of history. Over the millennia the world has moved away from barbaric practices like human sacrifice and sadistic executions, and over the millennia people have been living longer and in greater comfort. Countries that were at the leading edge of the abolition of cruelty, such as 17th-century England and Holland, were also among the more affluent countries of their time. And today it is in the poorer corners of the world that we continue to find backwaters with slavery, superstitious killing, and other barbaric customs.

129

The hypothesis that life used to be cheap but has become dearer loosely fits within the broad sweep of history. Over the millennia the world has moved away from barbaric practices like human sacrifice and sadistic executions, and over the millennia people have been living longer and in greater comfort. Countries that were at the leading edge of the abolition of cruelty, such as 17th-century England and Holland, were also among the more affluent countries of their time. And today it is in the poorer corners of the world that we continue to find backwaters with slavery, superstitious killing, and other barbaric customs.

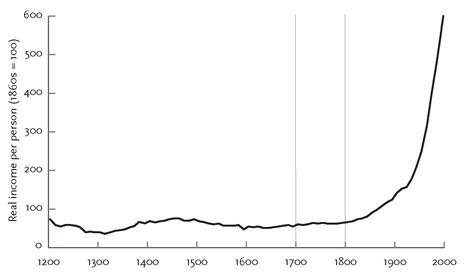

But the life-was-cheap hypothesis also has some problems. Many of the more affluent states of their day, such as the Roman Empire, were hotbeds of sadism, and today harsh punishments like amputations and stonings may be found among the wealthy oil-exporting nations of the Middle East. A bigger problem is that the timing is off. The history of affluence in the modern West is depicted in figure 4–7, in which the economic historian Gregory Clark plots real income per person (calibrated in terms of how much money would be needed to buy a fixed amount of food) in England from 1200 to 2000.

Affluence began its liftoff only with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. Before 1800 the mathematics of Malthus prevailed: any advance in producing food only bred more mouths to feed, leaving the population as poor as before. This was true not only in England but all over the world. Between 1200 and 1800 measures of economic well-being, such as income, calories per capita, protein per capita, and number of surviving children per woman, showed no upward trend in any European country. Indeed, they were barely above the levels of hunter-gatherer societies. Only when the Industrial Revolution introduced more efficient manufacturing techniques and built an infrastructure of canals and railroads did European economies start to shoot upward and the populace become more affluent. Yet the humanitarian changes we are trying to explain began in the 17th century and were concentrated in the 18th.

FIGURE 4–7.

Real income per person in England, 1200–2000

Real income per person in England, 1200–2000

Source:

Graph from Clark, 2007a, p. 195.

Graph from Clark, 2007a, p. 195.

Even if we could show that affluence correlated with humanitarian sensibilities, it would be hard to pinpoint the reasons. Money does not just fill the belly and put a roof over one’s head; it also buys better governments, higher rates of literacy, greater mobility, and other goods. Also, it’s not completely obvious that poverty and misery should lead people to enjoy torturing others. One could just as easily make the opposite prediction: if you have firsthand experience of pain and deprivation, you should be unwilling to inflict them on others, whereas if you have lived a cushy life, the suffering of others is less real to you. I will return to the life-was-cheap hypothesis in the final chapter, but for now we must seek other candidates for an exogenous change that made people more compassionate.

One technology that did show a precocious increase in productivity before the Industrial Revolution was book production. Before Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1452, every copy of a book had to be written out by hand. Not only was the process time-consuming—it took thirty-seven persondays to produce the equivalent of a 250-page book—but it was inefficient in materials and energy. Handwriting is harder to read than type is, and so handwritten books had to be larger, using up more paper and making the book more expensive to bind, store, and ship. In the two centuries after Gutenberg, publishing became a high-tech venture, and productivity in printing and papermaking grew more than twentyfold (figure 4–8), faster than the growth rate of the entire British economy during the Industrial Revolution.

130

130

Other books

Only the Stones Survive: A Novel by Morgan Llywelyn

The Bastard by Jane Toombs

Wexford 18 - Harm Done by Ruth Rendell

The Lost Souls' Reunion by Suzanne Power

Love on Call by Shirley Hailstock

Seagulls in the Attic by Tessa Hainsworth

The Art of French Kissing by Kristin Harmel

Body of Glass by Marge Piercy

Wreckage by Emily Bleeker

The Woman Destroyed by Simone De Beauvoir