The Black History of the White House (2 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

INTRODUCTION

African Americans and the Promise of the White House

I, too, am America

âLangston Hughes, from his poem “I, Too, Sing America”

More than one in four U.S. presidents were involved in human trafficking and slavery. These presidents bought, sold, bred and enslaved black people for profit. Of the twelve presidents who were enslavers, more than half kept people in bondage at the White House. For this reason there is little doubt that the first person of African descent to enter the White Houseâor the presidential homes used in New York (1788â1790) and Philadelphia (1790â1800) before construction of the White House was completeâwas an enslaved person.

1

That person's name and history are lost to obscurity and the tragic anonymity of slavery, which only underscores the jubilation expressed by tens of millions of African Americansâand perhaps billions of other people around the worldâ220 years later on November 4, 2008, when the people of the United States elected Barack Obama to be the nation's president and commander in chief. His inauguration on January 20, 2009, drew between one and two million people to Washington, D.C., one of the largest gatherings in the history of the city and more than likely the largest presidential inauguration to date.

2

Taking into account

the tens of millions around the globe who watched the event live via TV or Internet, it was perhaps the most watched inauguration in world history. It was of great international interest that for the first time in U.S. history, the “first family” in the White House was going to be a black family.

Obama has often stated that he stands on the shoulders of those who came before him. In terms of the White House, this has generally been seen to mean those presidents he admires, such as Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, who all inspired him in his political career. However, he is also standing on the shoulders of the many, many African Americans who were forced to labor for, were employed by, or in some other capacity directly involved with the White House in a wide array of roles, including as slaves, house servants, elected and appointed officials, Secret Service agents, advisers, reporters, lobbyists, artists, musicians, photographers, and family members, not to mention the activists who lobbied and pressured the White House in their struggle for racial and social justice. As the Obama family resides daily in the White House, the narratives of these individuals resonate throughout their home.

The black history of the White House is rich in heroic stories of men, women, and youth who have struggled to make the nation live up to the egalitarian and liberationist principles expressed in its founding documents, including the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. For over 200 years African Americans and other people of color were legally disenfranchised and denied basic rights of citizenship, including the right to vote for the person who leads the country from the White House. But despite the oppressive state of racial apartheid that characterized the majority of U.S. history, in the main, as Langston Hughes reminds us, black Americans have always claimed that they too are American.

At the end of the nineteenth century, when Jim Crow segregation and “separate but equal” black codes were aggressively enforced throughout the South, few African Americans were permitted to even visit the White House. As Frances Benjamin Johnston's 1898 photo on the cover of this book indicates, however, black children were allowed to attend the White House's annual Easter eggârolling ceremony. Permitting black children to integrate with white children on the White House premises one day a year was acceptable, even though such mingling was illegal in many public spaces throughout the South at the time, including libraries and schools.

The Easter eggârolling tradition had begun on the grounds of the Capitol, but concern over damage to the grounds led to the 1876 Turf Protection Law, which ended the practice at that site. Two years later, President Hayesâwho had won the presidency by promising to withdraw federal troops protecting African Americans in the South from whites who opposed black voting and political rightsâopened the White House's south lawn for the event. By the time of Johnston's photo, the 1896

Plessy v. Ferguson

decision legalizing segregation had been implemented, the last of the black politicians elected to Congress would soon be gone by 1901, and accommodationist black leader Booker T. Washington, who was also photographed by Johnston, was on the ascendant.

For many African Americans, the “white” of the White House has meant more than just the building's color; it has symbolized the hue and source of dehumanizing cruelty, domination, and exclusion that has defined the long narrative of whites' relations to people of color in the United States. Well before President Theodore Roosevelt officially designated it the “White House” in October 1901, the premises had been a site of black marginalization and disempowerment, but also of resistance and struggle. Constructed in part by black slave labor, the home and office of the president of the United States has embodied different principles for different people. For whites, whose social privileges and political rights have always been protected by the laws of the land, the White House has symbolized the power of freedom and democracy over monarchy. For blacks, whose history is rooted in slavery and the struggle against white domination, the symbolic power of the White House has shifted along with each president's relation to black citizenship. For many whites and people of color, the White House has symbolized the supremacy of white people both domestically and internationally. U.S. nativists with colonizing and imperialist aspirations understood the symbolism of the White House as a projection of that supremacy on a global scale.

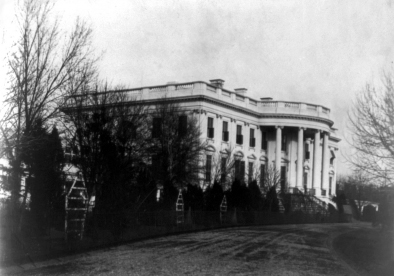

What the White House looked like while human trafficking and enslavement of black people was thriving in Washington, D.C., 1858.

Centuries of slavery, brutally enforced apartheid, and powerful social movements that ended both, are all part of the

historical continuum preceding the American people's election of Barack Obama. Few people, black or otherwise, genuinely thought that they would live to see what exists today: a black man commanding the presidency of the United States and a black family running the White House. Despite important advances in public policy and popular attitude since the social movements of the 1950s, '60s and '70s, for the many people of color who lived through the segregation era and experienced the viciousness of racists, the complicity of most of their white neighbors, and the callous disregard and participation of city, state, and national authorities, Obama's election was a moment never imagined. It was never imagined, in part, because of the misleading and unbalanced history we have been taught.

The Struggle over Historical Perspective

History is always written wrong, and so always needs to be rewritten.

3

âGeorge Santayana

U.S. history is taughtâand for the most part, learnedâthrough filters. In everything from schoolbooks and movies to oral traditions, historical markers, and museums, we are presented with narratives of the nation's history and evolution. For generations, the dominant stories have validated a view that overly centralizes the experiences, lives, and issues of privileged, white male Americans and silences the voice of others. It has been as though some have an entitlement to historic representation and everyone else does not.

But it is more than a matter of marginalization and silencing. History is not just a series of dates and facts, but more important, involves interpretation, analysis, and point of view. Historic understanding shapes public consciousness, and thus politics and policy decisions, social relations, and access to resources and opportunity. The dominant narratives of U.S. history elevate the nation's development through a perspective that reduces the vast scale and consequences of white enslavement of blacks, “Indian removal,” violent conquest, genocide, racism, sexism, and class power. The generations of lives, experiences, and voices of marginalized and silenced Americans offer an array of diverse interpretations of U.S. history that have largely gone unheard, unacknowledged, and unrewarded. Without their perspectives, we are presented with an incomplete and incongruent story that is at best a disservice to the historical record and at worst a means of maintaining an unjust status quo.

African American school children facing the Horatio Greenough statue of George Washington at the U.S. Capitol, circa 1899.

In education, the field of Black History and other areas of what are generally referred to as Ethnic Studies have attempted to serve as counter-histories, seeking to include the communities and individuals that have too often been written out of the national story. Scholars have attempted not only to correct the

record but also to restore a dignity and respect obliterated in official chronicles. These efforts have met with fierce resistance, from the beginning up to the present moment. In spring 2010, conservatives in Arizona not only passed SB 1070, which authorizedâin fact, demandedâthat law enforcement officers question the immigration status of anyone they deemed suspicious and who looked like they did not belong in the country, but also enacted HB 2281, which bans schools from teaching Ethnic Studies courses. While the former promotes racial profiling, the latter guarantees a continuing ignorance of the social diversity, history, and interests of everyone except white Americans. Framing education about the history of people of color in the worst possible manner, the law states, “Public school pupils should be taught to treat and value each other as individuals and not be taught to resent or hate other races or classes of people.”

4

Specifically aimed at Mexican, indigenous, and black studies, the law generated copycat efforts elsewhere, just as attempts to reproduce the anti-immigrant SB 1070 spread to other U.S. states in the expanding culture war over whose history deserves state and political support and promotion.

The challenge of presenting an alternative and more inclusive history of the White House lies not so much in finding the details and facts of other voices, in this instance black voices, but in challenging the long-standing views and dominant discourses that permeate all aspects of our public and popular education. The White House itself is figuratively constructed as a repository of democratic aspirations, high principles, and ethical values. For many Americans, it is an act of unacceptable subversion to criticize the nation's founders, the founding documents, the presidency, the president's house, and other institutions that have come to symbolize the official story of the United States. Understandably, it is uncomfortable to give up long-held and

even meaningful beliefs that in many ways build both collective and personal identities. However, partial and distorted knowledge is detrimental, and only through a more diverse voicing of the nation's experience and history, in this case of the White House, can the countryâas a peopleâmove forward.

Race, the Presidency, and Grand Crises

You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.

5

âRahm Emanuel, Barack Obama's White House chief of staff

Even after the celebrations of Obama's historic triumph, achieved with nearly unanimous support from African Americans and the votes of tens of millions of progressives, a nagging question remained:

What would the Obama White House mean for racial progress in the United States?

Will the Obama presidency generate the kind of historic policies that emerged under Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson to create greater racial equality, or will Obama's contribution be more symbolic, as Bill Clinton's was? Will having a black president make a difference, and if so, what kind of difference?

United States history has shown that opportunity for sustainable and qualitative social reform, including in the area of race relations, typically arises from a crisis leveraged by massive social and political organizing, i.e., a crisis that threatens the ability of those in power to maintain governability and control. Presidents, and political leaders in general, are captives of the period and circumstances they inherit. Elected leaders have the potential to advance a political and policy agenda, but only within the limits of the social and broader historical constraints of their times. The political status quo is stubborn and, within a system of checks and balances such as exists in the United States, rarely elastic enough to answer civil society's incessant

call for change. It is only under extraordinary conditions, such as when the efforts of ordinary citizens are focused on social movements whose demands threaten the elites with crisis, that massive and fundamental social transformation occurs. This trend is particularly pronounced throughout the history of race relations in the United States. In other words, whether Obama will have the opportunity for major advancements in the area of race relations and social equality will depend much more on the evolution of the political balance of forces, the state of the economy, the viability of political and social institutions, and the ideological atmosphere than simply his will (or lack thereof).