The Black Pearl (9 page)

Authors: Scott O'Dell

"We wait for an hour," said the Sevillano. "That will give the manta time to find another boat to follow."

"We can wait for an hour or for a day," I said, "but he will be there still."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean that the one out there is the Manta Diablo."

It was too dark to see his face, but I knew that the Sevillano was staring at me as though I had lost all my senses.

"Santa Maria!" he cried. "I am aware that ignorant Indians believe in the Manta Diablo. But that you who have been to school and can read books, one of the mighty Salazars himself, should believe this fairy tale. Santa Rosalia, it surprises me!"

"Furthermore," I said, "he is waiting out there for the pearl and he will wait until he gets it."

The Sevillano was leaning against the boat. He stood up and came over to where I sat.

"If I throw the pearl into the sea," he said, "the manta will take it, swim away and leave us alone. Is that what you are getting at?"

"Yes."

The Sevillano turned his back and walked over to the boat and gave it a thump with his foot, I guess to show his disgust. He then strolled off in the dark, as if he wished to be as far away from me as possible.

The moon rose. Soon afterwards, from the hill above, I heard the soft cries and rustle of birds. Something had disturbed the terns that had flown in at sunset to nest. As I glanced up, I saw a figure outlined against the sky.

I jumped to my feet, but did not call to the Sevillano. Here was a chance to rid myself of him. I could climb the hill and tell the Indian who stood there why I had landed on the island. He might give me help, for he would understand about the Manta Diablo.

It was a dangerous plan, yet it might have succeeded had not the Sevillano seen the Indian, too.

"We go!" he shouted.

I hesitated for a moment, watching the Indian on the hill above me. The nesting terns began to scream and flutter about, so I was certain that other Indians had come up from the village to join him.

The Sevillano ran to the boat and turned it over and stowed the supplies that lay on the sand.

"Hurry," he shouted at me.

I walked over to the boat and helped him shove it into the water. Where the pearl was I did not know, whether hidden in the boat or in his pocket.

"Perhaps you would like to stay," the Sevillano said. "The Indians of Los Muertos dig a pit in the sand and put you in it up to your chin and then let the turtles nibble at your face. But maybe you would like this better than the Manta Diablo."

The boat was floating and the Sevillano had picked up the oars.

"Do you go or stay?" he said.

A shower of arrows came whistling down from the hill and struck the sand. There was nothing for me to do now except to scramble into the boat, which I did just as a second flight of arrows churned the water around us.

The moon was near to full and the air was clear and the sea stretched away like a bed of silver. There were no signs of the Manta Diablo. The Sevillano put up the sail, though the wind had died, and both of us rowed hard, fearing that the Indians would launch their canoes. For a long time we heard their shouts, but they did not try to follow us.

When we left the lee of the island, we picked up a light breeze. The Sevillano reset the sail and took a sight on the North Star and steered the boat eastward along the moon's path.

A

T SUNRISE

the island of Los Muertos lay behind us. The air was heavy and scarcely a ripple showed on the sea. Over and around us hung a thin, red mist, but I did not locate the Manta Diablo until more than an hour had passed.

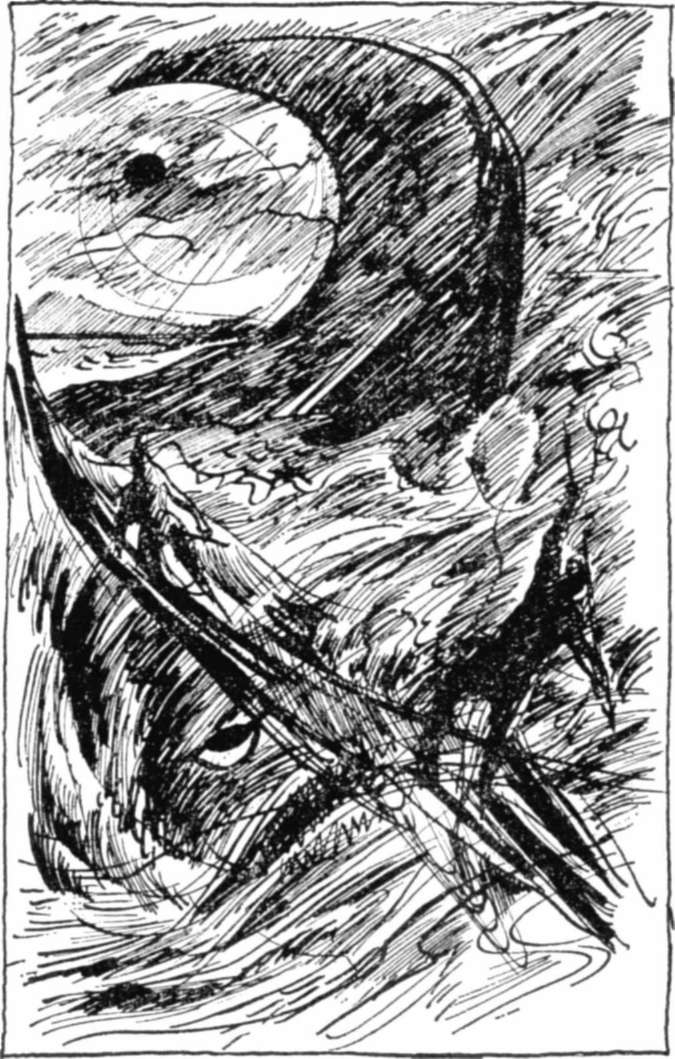

It was then that a needlefish, longer than my arm, skimmed the water and flew by me like a bullet. I heard the chattering of its green teeth and as I turned around to see what ever could have frightened a fish that is noted for its courage, the water heaved up half a furlong behind the boat. From this hillock rose the manta.

Through a shower of foam he rose high into the air, higher than I ever had seen one leap before, so high that I could see the flash of his white undersides and his long tail whipping about. There he seemed to rest for a moment or two, as if to survey all that lay about him, then down he came and struck the water a thunderous blow.

"Your friend shows off," said the Sevillano.

He spoke calmly and I looked at him, wondering that now, even now he did not know that it was the Manta Diablo who had leaped into the air and why he had done so.

The Sevillano took the pearl from between his feet and wedged it behind the jug of water in the stern of the boat and picked up the harpoon.

"I have killed nine mantas," he said. "They are much easier to kill than whales of the same size, because they lack the blubber of the whale. They are also easier to kill than the thresher shark or the six-gill or seven-gill shark or the tiger shark or the big gray one."

The Manta Diablo sank from view. It was nearly noon before I saw him again. A light wind came up and ruffled the sea and it might have been that he swam there close behind us all the time the Sevillano was telling me how simple it was to kill a manta and where he had killed the nine.

I first saw the outstretched wings and then he passed the boat and I saw the amber eyes turn and look at me as they had once before. They said as clearly as if the words were spoken, "The pearl is mine. Throw it into the sea. It has brought you ill fortune and ill fortune will be yours until you give it back."

I must have muttered something at this moment that betrayed my fear, for the Sevillano squinted his eyes and studied me. He was certain at last that he had a child or a crazy man to deal with.

The Manta Diablo swam by just out of range of the harpoon. Majestically he swam on ahead of us and came slowly back in a wide circle. The Sevillano waited for him with his feet spread apart and one leg braced against the tiller and the heavy harpoon in his hand.

The pearl lay beyond my reach. I would need to crawl the length of the boat to get at it. Any movement I made now he would see, so I decided to wait until the Manta Diablo drew closer and the Sevillano would have his mind fixed upon him.

Again the Sevillano looked at me. "I am beginning to understand a few things," he said in his soft voice, patiently as if he were talking to a child or someone bereft. "You stole the pearl from the Madonna because She failed to protect the fleet or your father. You traveled all night to the lagoon where you had found the pearl. And you went there to give it back to the Manta Diablo. Is this right?"

I did not answer him.

"Well," he said, "let me tell you something. It is news that you do not know, that no one knows except Gaspar Ruiz." He was silent for a moment, watching the Manta Diablo. "But for one small matter, at this very hour the fleet might be sailing under these same skies or riding safely at anchor in the harbor of La Paz. And your father might be sitting down in his patio to a feast of roast pig and good wine from Jerez."

Anger seized me. I sat quietly and did not move, but the Sevillano saw it on my face.

"Calm yourself," he said, "for I only wish to tell you why the fleet was wrecked upon the rocks of Punta Maldonado. A better one never sailed the Vermilion. Your father was a fine captain. Yet ships and men and your father all went down in a storm no worse than others they had lived through. Why, you ask."

"I ask nothing."

"But I will tell you, mate, because it may take me some time to get rid of the manta. While I am busy and not keeping a watchful eye, you might get a crazy idea. You might take the pearl and throw it overboard. Then I would have to slit your throat. That would be a shame, for the manta did not cause your father's death."

The Manta Diablo was still a good distance away and seemed in no hurry to overtake us, idly lifting and lowering his beautiful dark fins. But the Sevillano fastened one end of the harpoon rope and coiled the rest in a neat pile at his feet.

"When the storm was gathering," he said, "when the whole southern sky was filled with fearsome clouds, I told your father that we should turn back and seek shelter at Las Ãnimas. He laughed at me. The wind, he said, was with us and we could reach port before the storm struck. It was a bad decision, he made. And he made it because of the pearl, because of his gift to the Madonna. Not that he ever spoke of the pearl. Oh, no, not once did he mention it while we stood and argued and the wind blew and the clouds banked higher. But all the time the black pearl was there in his mind. I could tell it was there, big and important. I could tell by the way he spoke."

The Sevillano paused and raised his chin, striking a pose to show how my father had looked. It reminded me of the moment in the parlor when he had given the pearl to Father Gallardo and afterwards when he told my mother that the House of Salazar would be favored in Heaven, now and forever.

"I could tell," the Sevillano went on, "by the way he spoke, so sure about the storm and everything, that he felt, he knew that God had hold of his hand."

The Sevillano ran a finger over the iron barb of the harpoon and sighted along the shaft and made a few practice thrusts in the air. While he was doing these things, he said, "If you had the choice to make over again, would you steal the pearl from the Madonna?"

I hesitated to answer him, confused as I was by what I had just heard and by his question. Before I could speak, he said,

"No, Ramón Salazar would not steal the pearl. Of course not, now that he knows why the fleet was wrecked. Nor would he steal the pearl from his good pal, Gaspar Ruiz."

The Sevillano waited for me to answer, but I was silent. I sat in the bow of the boat and watched the Manta Diablo swimming effortlessly along behind us. Already I had decided what I would do if he killed the Manta Diablo or if he failed. Whether it was one or the other, I now saw clearly how I must act and that this I would not tell him.

T

HE

M

ANTA

D

IABLO

swam by once more, again just out of reach, and made a wide circle and came back. As he overtook the boat for the third time that morning, he passed closer than before. It seemed that this time he was daring the Sevillano to throw the harpoon, for the amber eyes of the monster were fixed upon him and not upon me.

The Sevillano gave a loud grunt and I heard the harpoon leave his hand and the rope twisted like a snake and shot upwards. A loop caught my foot and I was thrown against the bulwarks. I thought for an instant that I would be dragged into the sea, but somehow the rope came loose.

Sprawled against the side of the boat, I saw the long harpoon curve outward and down and

then sink. It struck the Manta Diablo squarely between his outspread wings.

A moment later the rope which held the harpoon snapped taut and the boat leaped from the sea and fell back with a shudder that rattled my teeth. It then slid back and forth, but once the rope tightened again, it began to move forward.

"Your friend takes us in the right direction," said the Sevillano and settled down at the tiller as if he were on his way to a fiesta. "At this rate we should be in Guaymas by tomorrow."

But the Manta Diablo swam eastward for only a short distance and then turned and headed into the west. He swam slowly, so that no water came aboard, as if he did not wish to disturb us in any way. He swam along a path straighter than I could have charted with a compass, toward the place we both knew well.

"Now your friend takes us in the wrong direction," said the Sevillano. "However, they soon grow tired, these mantas."

Nonetheless, the morning wore on and noon came and still the Manta Diablo swam slowly westward.

About this time the Sevillano became restless. He no longer lounged at the tiller, his broad-brimmed hat cocked on one side. Instead, he handed over the tiller to me and took a place in the bow which gave him a better view of the sea-beast and the harpoon it treated like the prick of a pin.

From time to time he would say something to himself and then glance at me with a curious glint in his eyes. I began to wonder if at last he knew that his adversary was not one of the common mantas, which he had little respect for, but

the

Manta, the Manta Diablo itself.

I did not have long to wonder. As we came abreast of Isla de los Muertos, he jumped to his feet and drew the long, cork-handled knife from his belt. I thought he meant to cut the rope that bound us to the untiring monster. And for an instant this may have been in his mind, but then with an oath he put the knife away and started to haul on the rope, hand over hand.

One hard-earned length at a time, he pulled the boat forward. The Manta Diablo did not change his pace nor his course through the quiet sea, so steadily we overtook him. In the end we were so near that I could have reached up and grasped his curved, rat-like tail.

At this point, the Sevillano tied the rope securely at the bow. He tossed his hat aside and took off his shirt and took the knife from his belt. He then filled his lungs with air and let it out with a sigh, thrice over, as if he were going down for a long dive.