The Blackwell Companion to Sociology (100 page)

Read The Blackwell Companion to Sociology Online

Authors: Judith R Blau

product might shape policies that may ultimately benefit people like themselves.

As I read a formatted statement to research participants, I placed little conviction in those words, and I believe that the study participants interpreted those words as empty promises as well. People engaged in the research less in expectation that by doing so they would help to formulate more just immigration policies but

more, I believe, in the expectation that their research relationship with me could be a non-threatening and even a personally beneficial, advantageous one. Rarely

did subjects or others in the community inquire about the potential benefits that they might derive from the finished research product.

Research Findings

In various social settings ± at picnics, at baby showers, at parish legalization clinic, and in people's homes ± I observed immigrant women engaged in lively

conversation about paid domestic work. Women traded cleaning tips; tactics

about how best to negotiate pay, how to geographically arrange jobs so as to

minimize daily travel, how to interact (or more often avoid interaction) with

clients, and how to leave undesirable jobs; remedies for physical ailments caused by the work; and cleaning strategies to lessen these ailments. The women were

quick to voice disapproval of one another's strategies and to eagerly recommend

alternatives.

The ongoing activities and interactions among the undocumented Mexican

immigrant women led me to develop the organizing concept of ``domestics'

networks,'' immigrant women's social ties among family, friends, and acquaint-

ances that intersect with housecleaning employment. These social networks

are based on kinship, friendship, ethnicity, place of origin, and current residential locale, and they function on the basis of reciprocity, as there is an implicit obligation to repay favors of advice, information, and job contacts. In some

cases these exchanges are monetized, as when women sell ``jobs'' (i.e. leads for customers or clients) for a fee. Information shared and transmitted through

the informal social networks was critical to domestic workers' abilities to

improve their jobs. These informational resources transformed the occupation

from one single employee dealing with a single employer to one in which

employees were informed by the collective experience of other domestic

workers.

The Job Search and Contracting

Although the domestics' networks played an important role in informally regu-

lating the occupation, jobs were most often located through employers' informal

networks. Employers typically recommended a particular housecleaner among

friends, neighbors, and co-workers. Although immigrant women helped one

another to sustain domestic employment, they were not always forthcoming

with job referrals precisely because of the scarcity of well paid domestic jobs.

Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo

429

Competition for a scarce number of jobs prevented the women from sharing job

leads among themselves, but often male kin who worked as gardeners or as horse

stable hands provided initial connections. Many undocumented immigrant

women were constantly searching for more housecleaning jobs and for jobs

with better working conditions and pay.

Since securing that first job is difficult, many newly arrived immigrant women

first find themselves subcontracting their services to other more experienced and well established immigrant women who have steady customers. This provides an

important apprenticeship and a potential springboard to independent contract-

ing (Romero, 1987). Subcontracting arrangements can be beneficial to both

parties, but the relationship is not characterized by altruism or harmony of

interests. In this study, immigrant women domestics who took on a helper did

so in order to lighten their own workload and sometimes to accommodate newly

arrived kin.

For the new apprentice, the arrangement minimizes the difficulty of finding

employment and securing transportation, facilitates learning expected tasks and

cleansers, and serves as an important training ground for interaction with

employers. Employee strategies were learned in the new social context.

Women sometimes offered protective advice, such as not to work too fast or

be overly concerned with all crevices and hidden corners when first taking on a

new job.

A subcontracted arrangement is informative and convenient for an immigrant

woman who lacks her own transportation or possesses minimal English-lan-

guage skills, but it also has the potential to be a very oppressive labor relationship. The pay is much lower than what a woman might earn on her own. In some

instances, the subcontracted domestics may not be paid at all. These asymmet-

rical partnerships between domestic workers continue for relatively long periods of time. Although subcontracting arrangements may help domestics to secure

employment with multiple employers, the relationship established between the

experienced, senior domestic and the newcomer apprentice is often a very

exploitable one for the apprentice.

The Pay

Undocumented immigrant women in this study averaged $35±50 for a full day of

domestic work performed on a job basis, although some earned less and others

double that amount. What determines the pay scale for housecleaning work?

There are no government regulations, corporate guidelines, management policy,

or union to set wages. Instead, the pay for housecleaning work is generally

informally negotiated between two women, the domestic and the employer.

The pay scale that domestics attempt to negotiate for is influenced by the

information that they share among one another and by their ability to sustain

a sufficient number of jobs, which is in turn also shaped by their English-

language skills, legal status, and access to private transportation. Although the pay scale remains unregulated by state mechanisms, social interactions among

the domestics themselves serve to informally regulate pay standards.

430

Immigrant Women and Paid Domestic Work

Unlike employees in middle-class professions, most of the domestic workers

that I observed talked quite openly with one another about their level of pay. At informal gatherings, such as a child's birthday party or community event, the

women revealed what they earned with particular employers and how they had

achieved or been relegated to that particular level of pay. Working for low-level pay was typically met with murmurs of disapproval or pity, but no stronger

sanctions were applied. Conversely, those women who earned at the high end

were admired.

As live-out, day workers, these immigrant women were paid on either an

hourly or à`job work'' basis, and most women preferred the latter. Being paid

por trabajo, or by the job, allowed the women greater flexibility in caring for

their own families' needs. And with regard to income, being paid by the job

instead of an hourly rate increased the potential for higher earnings. Women

who were able to work relatively fast could substantially increase their average earnings by receiving a set fee for cleaning a particular house. If they could

schedule two houses a day in the same neighborhood, or if they had their own

car, they could clean two and sometimes even three houses in one day.

Using Ethnographic

Ethnographic Findings

Findings for Advocacy

In every major US city with a large immigrant population, large umbrella

coalitions that include community, church, legal, and labor groups are now

working to establish and defend civil rights and workplace rights for immigrants and refugees. Two key features distinguish these efforts. First, the claims are

typically made outside the traditional and exclusive category of US citizenship.

Second, until recently many of these efforts were aimed only at male immigrants.

For various reasons, among them thèìnvisibility'' of immigrant women's

employment, immigrant rights advocates have been slower to defend immigrant

women's labor rights. But this is changing.

A year and a half after completing the research, I began meeting with a group

of lawyers and community activists associated with the Coalition for Humane

Immigrant Rights in Los Angeles to plan an information and outreach program

for paid domestic workers, the majority of whom in Los Angeles are Latina

immigrant women. It was in this context that I utilized some of the research

findings on immigrant women and domestic employment.

The newly formed committee met for one year before launching an innovative

informational outreach program. The planning stage was long because of the

obstacles that this occupation poses for organizing strategies and because the

group was not working from an existing blueprint. How to organize paid

domestic workers who work in isolated, private households is neither easy nor

obvious. There are no factory gates through which all employees pass, and

instead of confronting only one employer, one finds that the employers are

nearly as numerous as the employees. Traditional organizing strategies with

paid domestic workers encompass both trade unions and job cooperatives (see

Chaney and Castro, 1989; Salzinger, 1991), but both models necessarily build in

Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo

431

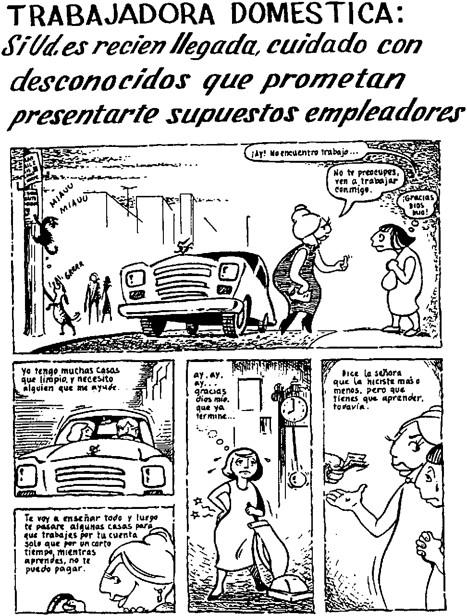

Figure 29.1 Domestic workers: if you have just arrived be careful with strangers who promise to introduce you to supposed employers.

432

Immigrant Women and Paid Domestic Work

Figure 29.2 Keep these three things in mind.

Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo

433

numerical limitations. Our group decided that reaching workers isolated within

multiple residential workplaces could best be accomplished through mass media

and distribution of materials at places where paid domestic workers are likely to congregate, such as on city buses and in public parks. The key materials in our

program were novelas.

Novelas are booklets with captioned photographs that tell a story, and they

are typically aimed at working-class men and women. In recent years immigra-

tion rights advocates in California have successfully disseminated information

regarding legalization application procedures, legal services, and basic civil

rights to Latino immigrants using this method, and in southern California,

even the Red Cross has developed a novela on AIDS awareness. Our group

developed the text for several didactic novelas, and in lieu of photographs, we

hired an artist to draw the corresponding caricatures. One novela centers on

hour and wage claims, and another was designed as an emergency measure to

alert domestic workers that a rapist was getting women into his car by offering

domestic work jobs to women waiting at bus stops. Based on the research with

paid domestic workers, I prepared a two-sided novela sheet that cautions women

about the abuses in informal subcontracting relations, underlines that payment

by thè`job'' or house yields higher earnings than hourly arrangements, and

recommends that domestic workers share cleaning strategies and employment

negotiation strategies with their friends. The text also reminds women of their

entitlement to receive minimum wage ($4.25).

With a small grant, the advocacy group hired four Latina immigrant outreach

workers, two Salvadoran women and two Mexican women, to distribute these

materials to Latina immigrant domestic workers. Posters were printed up and

placed on over 400 municipal buses that run along east±west routes. In large black print written across a red background the text reads (in Spanish): ``Domestic