The Bletchley Park Codebreakers (9 page)

Read The Bletchley Park Codebreakers Online

Authors: Michael Smith

The traffic intercepted by the Y service intercept stations was sent to Hut 6 by teleprinter so far as possible: the signals were preceded by a register with their preambles, which were transmitted immediately a full page was ready. Incoming traffic was first sorted by an identification party in the Hut 6 watch registration section into operational traffic, which was processed urgently, and non-operational, which had to wait. Operational messages then went to Registration Room No. 1, where a ‘discriminatrix’ sorted them by cipher system, using their discriminants and other data. Their preambles were then registered in a ‘blist’ (Banister list).

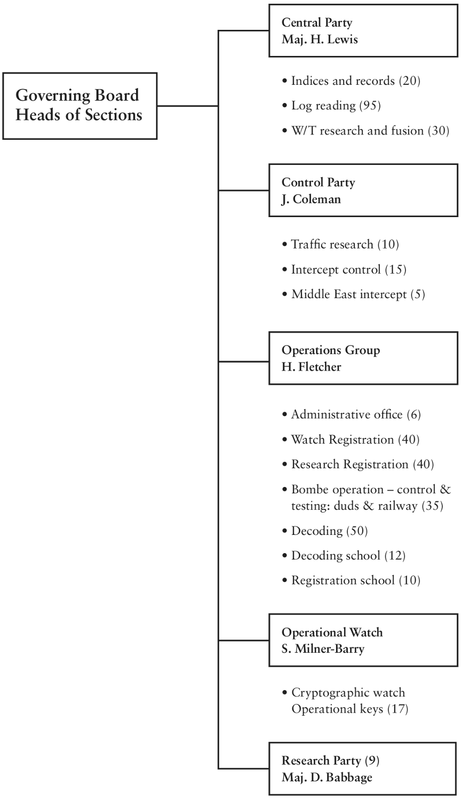

Figure 4.2 Hut 6 organisation chart

17th May 1943, Head Gordon Welchman (400 staff)

Operational messages were examined immediately by the cryptanalytic operational watch, which selected some from which to construct bombe menus. When a key was found by the bombes, the traffic using it was sent to the decoding room, where the signals were run through British Typex cipher machines, which had been converted to emulate Enigma. This part of deciphering the traffic was far from being a straightforward process: up to two-thirds of the messages could present deciphering difficulties – so-called ‘duds’ – messages which would not decipher, generally because they had the wrong indicators or contained garbled cipher text. The resulting decrypts were first routed through a room called the ‘cubicle’ for indexing, before being sent to Hut 3 for translation and analysis. A small section in the bombe control room (which was part of Hut 11A, where the Bletchley Park bombes were housed) processed duds. If the section could not decipher a message, it was sent to the log readers in the central party. By late 1944, the number of ‘tries and duds’ being attempted by Hut 6 had increased enormously, to an average of 1,125 per day (compared with 2,050 decrypts) in the week ending 7 October. Stuart Milner-Barry, the head of Hut 6 from September 1943 onwards, considered that a 2:1 ratio was about ‘the best that we can do under favourable circumstances’.

The central party analysed the logs kept by the intercept operators in order to build up a geographical picture of the complex German radio nets, which constantly changed call signs and frequencies in order to outwit the British. Since Enigma cryptanalysis was inseparable from traffic analysis, the central party’s work made an indispensable contribution to Hut 6’s successes. By early 1943, it was a far cry from the days when GC&CS ‘did not think that the results of traffic analysis were ever likely to help cryptanalysts’, and when Gordon Welchman was ‘deeply suspicious of Colonel Butler’s efforts to expand the W/TI [traffic analysis] organization’. John Coleman’s traffic research section in the control party was responsible for identifying the call signs used by the German transmitting stations under an intricate allocation system.

The log-reading section in the central party was the biggest single unit in Hut 6, with ninety-five staff in May 1943. The log

readers also looked for re-encipherments, routine cribs, cillies and ‘giveaways’ (cryptographic information in operators’ plain-language chat). Sometimes even the rotor orders or the

Stecker

were revealed by giveaways – operators on Brown were notorious for doing so. Re-encipherments occurred when a signal had to be sent from one cipher net, such as a

Fliegerkorps

, to another; they were more frequent at the beginning of a month, when new key-lists took effect. Re-encipherments could be identified from their times of origin, which were the same as the original signal, and their lengths, which were similar. The heads of the log-reading groups, with a few assistants, staffed the Fusion Room, which combined information from traffic analysis and cryptanalysis to build a complete picture of the Enigma radio nets, and fed it back in a unified form to the groups sending data to it.

Hut 6’s successes ultimately depended upon the comprehensive and accurate coverage of the

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

radio nets by the Y service, but regrettably the story of interception in 1939 and for much of 1940 ‘is not a pretty one’. In September 1939, there were twentyfive sets, manned by civilians, at the War Office intercept station at Chatham, which initially was the main intercept station for Enigma. In November 1939 and February 1940 the War Office warned Group Captain L. F. Blandy, the head of AI1e (which was responsible for interception in the Royal Air Force (RAF)), that if a major offensive began on the Western Front, Chatham would drop

Luftwaffe

Enigma traffic, which the RAF would then have to intercept. In April 1940, Denniston informed Blandy and Colonel D. A. Butler, of MI5, that ‘it is now of the highest importance that Y stations should concentrate as far as possible on German Enigma traffic (Air and Army) … I should be very grateful if you would issue orders to that effect’.

The Air Ministry agreed to intercept the Enigma traffic on 2 March 1940, but Hut 6 received nothing from it for many months. The root of the problem was that AI1e belonged neither to the RAF’s Director of Signals, who had some receivers and men but needed them for communications purposes, nor to the Director of Intelligence, who had no responsibility for intercept facilities and seems not to have realized that there was an intercept problem, since he was already receiving a great deal of intelligence – intercepted by the army. In April 1940, Denniston urged Menzies ‘most urgently to call a meeting of your Main Committee [on intercept co-ordination]’, adding that ‘no action has been taken to improve the position (in regard to interception of

Enigma traffic)’. But despite Denniston’s plea, little or nothing seems to have happened: the Y Committee did not consider the subject until July. In July, 85 per cent of the Chatham intercept facilities were allocated to Enigma, mostly

Luftwaffe

, yet no

Luftwaffe

Enigma was yet being intercepted by the RAF, which was just about to send forty operators to Chicksands (a naval Y station) for training.

In 1940, the services, mainly the War Office, and not the user (Hut 6), controlled the tasks undertaken by the stations. Around August 1940 Chatham even removed six sets from Enigma cover without notifying GC&CS. Hut 6 protested, but received scant sympathy from the military and Air Force authorities, who considered it ‘an act of grace on their part to allow GC and CS any voice in the allocation’ of sets. Hut 6 even had to give battle in order to prevent Enigma coverage being transferred from highly skilled Army operators to unskilled RAF personnel, with potentially disastrous results for breaking Enigma. Although RAF Y had not yet started to intercept any

Luftwaffe

ground to ground traffic, Blandy wrote patronizingly about Hut 6’s protest: ‘My only comment is that the authors of this document have just begun to understand the niceties of wireless interception. If they had all done a course at Chatham or Cheadle they would not have wasted so much paper.’

As more ciphers were broken and as the cover on them improved, more cribs and re-encipherments were discovered, which in turn required more intercept sets to exploit them. Hut 6 ideally needed coverage on every Enigma cipher, however unimportant it appeared to be, but in 1941 it had to complain about ‘the [lamentable and inexcusable] failure of the Army authorities to provide an adequate number of trained operators’. It is therefore not surprising that two postwar histories described the expansion of intercept facilities during 1940 as ‘astonishingly and lamentably slow’ and ‘the machinery of the Y services [as] not then functioning well’. By March 1941, Chatham’s complement of sets had only increased by two, to twenty-seven, although there was also a second Army station at Harpenden. A newly formed ‘E’ Sub-Committee of the Y Committee decided in March 1941 that 190 sets were needed for Enigma. One hundred and eighty Army, RAF and Foreign Office sets in Britain and abroad were taking Enigma traffic by November 1941. However, there was a shortage of skilled operators for many months, partly because ex-Post Office operators proved unsuitable. Militarizing personnel at the stations,

and forming an ATS intercept unit, was largely to prove the answer for the Army’s purposes. It turned out to be a slow process, and it was only in November 1942 that a set room, with thirty-six sets, was completely staffed by ATS at a new Army station, Beaumanor.

In January 1942, the Chiefs of Staff authorized a major expansion of all the Y services, including the recruitment of 7,150 additional personnel, together with the establishment of a much-needed radio network to handle traffic from overseas Y stations and outposts of GC&CS. The sets on Enigma at home and abroad increased from 210 in April 1942 to 322 in January 1943. The Army and Foreign Office provided 64 per cent of the intercept sets, but 60 per cent of the daily keys solved were

Luftwaffe

, and only 26 per cent

Heer

; 10 per cent were Railway daily keys, and 5 per cent were SS. On 3 March 1943, the Chiefs of Staff authorized a second Y expansion programme. By May 1943, the WOY G (War Office Y Group) at Beaumanor had 105 sets on

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

Enigma traffic, and the main RAF station at Chicksands, ninety-nine receivers. There were also sixty sets on Enigma at Foreign Office stations at Whitchurch, Denmark Hill, London (formerly a Metropolitan Police station) and Cupar, an Army station at Harpenden and RAF stations at Shaftesbury and Wick, plus seventy-five sets in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. By June 1944, 515 sets were tasked on

Luftwaffe

and

Heer

Enigma, but even as late as January 1945, Hut 6 was ‘as short of sets as ever’: minor

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

ciphers were not being intercepted, and no attempt could therefore be made to break them.

The service authorities came to accept Hut 6’s view that Enigma interception was an indivisible problem, and allocated Army sets to

Luftwaffe

traffic, and RAF sets to

Heer

signals. Later, they also relinquished control of tasking the Army and RAF sets. In May 1943 Hut 6’s intercept control section under John Coleman specified the Enigma tasks to be taken by the intercept stations, and the number of sets to be allocated, but the stations remained under the administrative control of their parent services. Coleman’s section also co-ordinated interception in the Middle East with interception in Britain.

Accurate interception was essential when attacking Enigma, since hours could be lost because of a single wrong letter or call sign, or even a mistake in measuring the frequency. Hut 6 was unable to break Yellow for 5 May 1940, because of a single incorrect letter in the intercept, although the Poles solved it on 7 May. When resources

allowed, radio nets were therefore often covered by two (or sometimes even six) sets to ensure that signals were precisely recorded. Only first-rate operators could deal with very faint signals coupled with interference, and drifting or split frequencies, but they were still in short supply even in December 1942. Hut 6 estimated that only about one third of the operators then at Beaumanor and Chicksands were first-rate, and another third, second-rate. Taking a burst of Morse from ‘a distant signal underneath the cacophony of different Morse transmissions, a diva singing grand opera in German, [and] a high-speed Morse transmission’ required a very high degree of skill.

Breaking Red was Hut 6’s most important task throughout the war, as can be seen from the number of radio receivers allocated to intercepting it: in July 1941, sixty-eight sets were taking Red – over half the 119 sets in Britain tasked on Enigma, although the proportion had declined slightly, to about 35 per cent (fifty sets) in October. The average daily traffic on Red of 380

Teile

(message parts) from June to November 1942 was 65 per cent of the total combined traffic (590

Teile)

intercepted on all the Army and SS cipher nets, while the average daily total of the

Luftwaffe

traffic (1,400

Teile)

was over double that of the

Heer

and SS. Red was easy to break once continuity had been established: the net was so widespread that if one crib went down there was a good chance of finding another to replace it. Red’s links to many other

Luftwaffe

keys made it possible to penetrate them by cribs from re-encipherments, which were known as ‘kisses’ in Bletchley Park parlance, because they marked the relevant signals with ‘xx’. Red was also an invaluable source of intelligence on

Heer

topics in North Africa and elsewhere.

Hut 6 solved the

Luftwaffe

Light Blue cipher, which provided intelligence about the

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

in Libya, within about eight weeks of its introduction in January 1941, and read it daily until it went out of service at the end of 1941. The only other

Luftwaffe

cipher intercepted in 1941, Mustard, the field cipher on the eastern front of the

Luftwaffe

Sigint service, the

Funkaufklärungsdienst

(Radio Reconnaissance Service), was solved for twelve days in the late summer, and from April 1942. It proved useful in giving the order of battle of the Soviet Army and Air Force, and by revealing the very considerable insecurity of Soviet ciphers.