The Body Economic (2 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

F

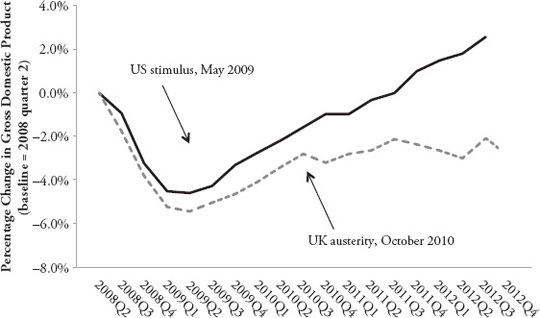

IGURE P.1

US Economy Is Recovering After Stimulus but UK Still in Recession After Austerity

2

This patternâthe benefits of stimulus, the harms of austerityâplays out in nearly a century of data on recessions and the economy, from countries all over the world.

Conventional wisdom holds that recessions are inevitably bad for human health. Thus, we ought to expect a rise in depression, suicide, alcoholism, infectious disease outbreaks, and many other health problems. But this is false. Recessions pose both threats and opportunities for public health, and sometimes can even improve health outcomes. Sweden had a massive economic crash in the early 1990s, larger than it experienced in the Great Recession, but saw no increase in suicides or alcohol-related deaths. Similarly, in

this recession we have seen health improve in Norway, Canada, and even for some people in the US.

4

F

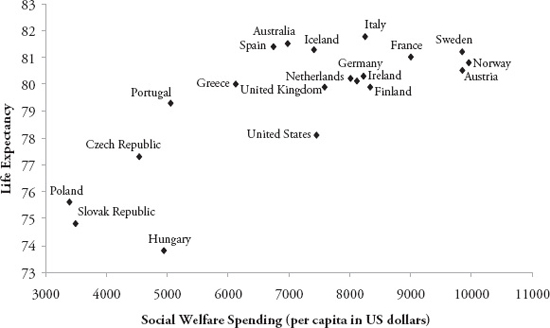

IGURE P.2.

Social Welfare Spending Increases Life Expectancy at Birth, Year 2008

3

What we've learned is that the real danger to public health is not recession per se, but austerity. When social safety nets are slashed, economic shocks like losing a job or a home can turn into a health crisis. As shown in

Figure P.2

, a strong determinant of our health is the strength of our social safety nets. When governments invest more in social welfare programsâhousing support, unemployment programs, old- age pensions, and healthcareâhealth improves for reasons we'll explain. And this is not merely a correlation, but a cause- and-effect relationship seen across the world.

That's why Icelandârocked by the worst bank crisis in historyâdidn't experience rising deaths in the Great Recession. It chose to uphold its social welfare programs, and went even further to bolster them. By contrast, Greece, Europe's guinea pig for austerity, was pressured to undertake draconian cutsâthe largest seen in Europe since World War II. Its recession was smaller than Iceland's at first, but now has worsened with austerity. The human costs have become dramatically clear: a 52 percent rise in HIV, a doubling in suicide, rising homicides, and a return of malariaâall as critical health programs were cut.

These dangers of austerity are as consistent as they are profound. In history, and decades of research, the price of austerity has been recorded in death statistics and body counts.

Too much of the conversation surrounding the Great Recession has focused on lost GDP, deficits, and debt reduction. Too little has focused on human health and well-being. In March 1968, Senator Robert Kennedy criticized this fetishization of economic growth:

Our gross national product now is over eight hundred billion dollars a year, but that gross national productâif we should judge the United States of America by thatâthat gross national product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwoods and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm, and it counts nuclear warheads, and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile, and it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

5

We take Robert Kennedy's proposition seriously. In The

Body Economic,

we focus on the choices that governments make and the implications of those choices not only for our economies, but also for our bodies. We now have extensive data that reveal which measures kill, and which save lives. As citizens, we can call on our governments to make the right decisionsâdecisions that protect our health during hard times.

Olivia remembers being on fire.

Eight years old, she was scared by the sound of dishes crashing onto the kitchen floor. Her parents were having another fight. She ran up the stairs to her bedroom and hid under a pillow. Exhausted from crying, she fell asleep.

1

She woke up with a splintering pain on the right side of her face. The room was black with smoke. Her bedsheet had erupted in flames. Screaming, she ran out of her room and straight into the arms of a firefighter who had raced up the stairs. He wrapped her tightly in a blanket. As she would later hear the nurses in the hospital whisper, her father had set the house on fire in a drunken rage.

It was the spring of 2009, during the ongoing Great Recession. Olivia's father, a construction worker, had been laid off. Millions of Americans had joined the unemployment rolls, and some turned to drugs or, like Olivia's dad, to alcohol.

2

Olivia's father ended up in jail. Olivia required extensive treatments for her burns and undoubtedly will need years of therapy to heal the mental scars from that horrible night.

But Olivia survived. Others were not so lucky.

Three years later and half a world away, on the morning of April 4, 2012, Dimitris Christoulas set off to the Greek Parliament building in the center of Athens. At age seventy-seven, he saw no other way out. Christoulas had been a pharmacist, retired in 1994, but now he was having trouble paying for his medications. Life had been good, but the new Greek government had slashed his pension, and life was now intolerable.

3

That morning, Christoulas went to Syntagma Square, the city's central plaza. He walked up the Parliament steps, put a gun to his head, and declared, “I am not committing suicide. They are killing me.” Then he pulled the trigger.

Later, a note found in his satchel was released.

4

In it Christoulas equated the new government to the widely hated World War II government of Georgios Tsolakoglou that collaborated with the Nazis:

The Tsolakoglou government has annihilated all traces for my survival, which was based on a very dignified pension that I alone paid for 35 years with no help from the state. And since my advanced age does not allow me a way of dynamically reacting (although if a fellow Greek were to grab a Kalashnikov, I would be right behind him) I see no other solution than this dignified end to my life, so I don't find myself fishing through garbage cans for my sustenance. I believe that young people with no future, will one day take up arms and hang the traitors of this country at Syntagma square, just like the Italians did to Mussolini in 1945.

“This was not suicide,” a protester later said. “He was murdered.” A mourner nailed a note to a tree near the spot where Christoulas died. “Enough is enough,” it read. “Who will be the next victim?”

Olivia and Christoulas may have been 5,000 miles apart, but their lives were woven together by the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. As two public health researchersâone at Stanford in California and the other at Oxford, En glandâwe became concerned that the Great Recession would take its toll on people's bodies. We heard stories from our patients, friends, and neighbors who lost their health insurance but also experienced harms that went well beyond the medical clinic or the pharmacy, intruding upon the very fabric of their livesâtheir ability to afford healthy food to eat, avoid the high stress of losing a job, and keep a roof over their heads. We wondered what impact the Great Recession would have on the rates of heart disease, of suicide and depression, and even the spread of contagious diseases.

In search of answers, we have mined data from around the globe and from decades of prior recessions. We've found that public health can be profoundly

affected by economic shocks. Some of our findings were expected. When people lose jobs, they are more likely to turn to drugs and alcohol or become suicidal. When they lose their homes, or are mired in debt, they often turn to junk food, for comfort or simply to save money.

Tragic as they are, the misfortunes of people like Olivia and Dimitris are unsurprising. More than 600 Greek citizens killed themselves in 2012. Before the Great Recession, Greece had the lowest suicide rate in Europe. Now that rate has doubled.

5

And Greece isn't alone. Suicides in the other European Union countries had been dropping consistently for over twenty years until the Great Recession.

But in our global research, we also encountered some surprises. Some communities, even entire nations, became

healthier

than ever as their economies were devastated. Iceland went through the worst bank crisis of all time, but the population's health actually improved. Health in Sweden and Canada also improved. Norway reached its highest life expectancy ever. But this had nothing to do with the cold climate. Japan, which had suffered a “lost decade” from the prolonged effects of recurrent recessions, now reports some of the best health statistics in the world.

Some economists looked at these data and concluded that recessions were “a lifestyle blessing in disguise,” the cause of these health gains. Thanks to losing income in the Great Recession, they argued, people would get healthy: drink and smoke less, and walk rather than drive. They were finding that recessions correlated with a drop in death rates in many places. Looking grimly into the future, one economist predicted that an economic recovery will kill 60,000 people in the United States. Such odd and counter-intuitive pronouncements are contradicted by data from health departments around the world. During the Great Recession, life expectancy in the United States appeared to fall in some counties for the first time in at least four decades. In London, heart attacks rose by 2,000 amid the market turmoil. And suicide and alcohol death reports keep piling up on our desks.

6

These data were a puzzle. How had some people become healthier during recessions, while others ended up like Olivia and Dimitris?

The answers could be found in the politics of the Great Recession. The 2012 US presidential election helped define a seemingly eternal debate between austerity and stimulus, services and revenue. Lo and behold, austerity lost. President Barack Obama campaigned on raising taxes on the wealthy and investing

in social services, and he won. As the US climbs slowly out of recession, other countries should take note. Britain, under a Conservative Party government since 2010, has enacted an austerity regime that has, as of January 2013, shown signs of sending the country back into recession.

Over the past decade, we've looked through reams of data and reports in search of answers. Austerity or stimulus? Cuts or hikes in taxes to the rich? Cuts or hikes in services to the poor? We traveled from the coldest gulag in Siberia, to the red-light district of Bangkok, to the biggest intensive-care unit in the United States to find answers. The data we've gathered lead irrevocably to this conclusion: societies that prevented epidemics during recessions almost always had strong safety nets, strong social protection.

Disasters like Olivia's inferno and Dimitris's suicide do not always follow economic downturns. Rather, they are the consequences of a simple political choiceâa choice to bail out bankers and cut safety nets for everyone else. Just a few key decisions, we've found, can stop a recession from turning into an epidemic. But our research shows that austerity involves the deadliest social policies. Recessions can hurt, but austerity kills.