The Body Electric - Special Edition (28 page)

Read The Body Electric - Special Edition Online

Authors: Beth Revis

“You think?”

Jack’s long strides make me pick up my pace as I follow him up. “I mean, I hope. But…”

“But…?”

“But we should keep going, that’s what I’m saying. Come on.”

The only sound in the cramped, narrow space is my and Jack’s footsteps on the slick stone. We slide on it every once in awhile, and my hands and knees are bruised and scratched by the time I climb the last stairs. This tunnel is ancient—so old it feels almost as if it were made by nature, not man, but the stairs we just climbed were clearly manufactured, albeit several centuries or more ago.

Jack grabs my arm and pulls me closer to him as he flicks on a small penlight I didn’t know he had.

“We’re finally here,” he says, his voice ragged from the exertion of climbing the steps.

“And where is here?”

“The cata—the exit,” he says quickly, but I already caught the word he was trying not to say. I take the flashlight from his hand and cast it around the tunnel.

It is filled with dead bodies.

Well, not bodies.

Skeletons.

Hundreds and hundreds of them.

“What is this place?” I whisper.

“Saint Paul’s catacombs,” Jack answers. He crosses the cavern and sets up his flashlight in the center of the room on a raised, circular dais. It casts light and shadow around the room. The entire area is carved directly from the rock. The smooth, slick floor, the low ceiling, the indentations in the walls filled with bones.

Through a stone window, I can see a long row of rectangular indentations carved into the rock, almost like narrow beds, each one filled with a skeleton. Many of the skeletons are too big for the indentations, and whoever laid the bodies there bent the arms and legs so they would fit.

“It was made in the Roman times,” Jack says. His voice is soft, but it bounces around the stone walls so that it sounds like each of the skeletons whispers to me. “The ancient bodies are long gone, but when the Secessionary War broke out, they started using the catacombs again, putting bodies in the loculi after they died.”

“They?” I ask.

“The poor. The ones who can’t afford cremation. When the bombs hit Valetta and the other towns, whole families were killed. But their friends and relatives didn’t have the proper materials or knowledge for preparing the bodies, and people who came here to entomb the dead started to get sick. The Zunzana closed off the catacombs again, fairly early on, and people had funerals at sea instead. That’s what the poor still do, the ones in the Foqra District.”

I’m reminded of what Jack said about the Zunzana, that it had existed for years before him, an organization that worked silently, correcting the mistakes of the government. It had once been vast and influential enough to help people bury their dead in wartime—and now it was just three teenagers, struggling to show the world an unspeakable evil.

The skeletons here are all blank, devoid of any personal features, most of them wrapped in a thin linen cloth. Some are only bones, but there are still several that have a slimy, waxy sheen to them. It is dank and dark here, but also cool, and the bodies do not rot as quickly as they would above ground.

I’m starting to envision faces on the cadavers. They didn’t die that long ago. These are not bodies from the ancient days; these people could have been my relatives. My grandparents, the uncle I never met, the cousins I never had.

And then I see a small hole carved into the wall, no longer than my arm, and a tiny skeleton inside it, and my heart cries out in horror. My hand shakes as I raise it, resting on the damp stone wall just below the baby’s tiny, bone fingers.

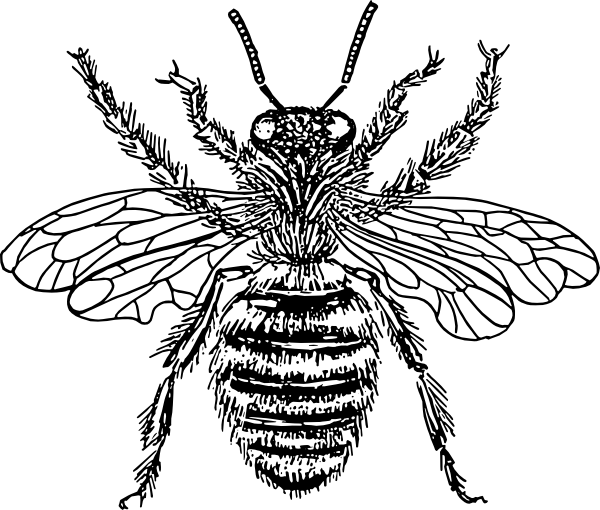

Beneath it is a slightly smaller crevice, and inside, the skeleton of someone a bit younger than me. A glint of gold shines in the light—a tiny metal bumblebee like the pin Jack wears, resting where the kid’s heart should be. These bones belong to someone like Jack. Someone like Charlie, the kid who ran off and distracted the police so I could escape. I gasp, overwhelmed by the emotions I’ve been trying to hold back for so long. I swallow down the lump in my throat. I cannot cry. I cannot cry.

I cannot stop crying.

Jack rushes around the table and touches my shoulder, hesitantly. I jerk away from him. I don’t want his comfort. I don’t

know

him, even if he thinks he knows me. But my eyes are blurry and burning, and I can’t choke down the sob rising in my throat.

I don’t know what it is. Seeing the dead bodies of children who died before I was born, victims of a war they never had a chance of winning? Or knowing that, when my body is dead and I start to rot, maybe it won’t be a human skeleton that will rest in my grave. I might not rot at all. I might be nothing more than an android, and death is as simple as a kill switch behind a bypass panel. What else can I be, to have a nanobot count like I do, to be able to do the things I have done?

Androids don’t feel

, I remind myself, and there is nothing I would like to do more now than to

not feel.

I sink to the floor, the wet stones soaking the seat of my jeans, and draw my knees up to my chest, hugging them against my body as my head sinks down, my short hair barely covering my face. I just want to be alone, but I feel the death of the tracker nanobots in my blood, and I cannot be alone, even from them. I am surrounded by death, inside and out, and all it does is remind me of how futile everything is, everything ever was.

I feel rather than see Jack sit down beside me. He doesn’t touch me. He just sits there, beside me, the only warmth in this cold, dead cave.

I look up when I feel a cool breeze on my skin, making goose bumps race along my arms.

“There are ventilation shafts,” Jack says, pointing up. I follow his finger, but see only darkness. I feel like I’ve lived in this darkness for so long that I will be blinded by sunlight.

“She’s really gone, isn’t she?” I say softly, staring at a glint of a copper ring around the finger of one of the skeletons resting in the wall across from me. It reminds me of the rose-gold ring my mother wears. I try to remember if the doppelganger of Mom had her ring, if that’s one more piece of her lost.

It takes Jack a moment to realize what I mean. “Your mother?” he asks.

I nod my head. “And Akilah.”

“I think so.” We both know that Akilah’s body was gone—we both saw it destroyed. But I had hoped that there was

something

left, something that was my friend. Something left of my mother beyond the metal skull and sparking electrical wires.

“How?” I ask simply.

Jack stares blankly ahead. “I’m not sure. At the Lunar Base, when a soldier died—and it happened far more than the news lets on, there are a lot of ‘accidents’ during training missions, and skirmishes from Secessionary States. Anyway, if a soldier died, he’d be replaced fairly quickly with a doppelganger. It didn’t take long for me to figure out something was wrong. All the soldiers in the Lunar Base were young—some of them younger even than the military should allow, mostly from the Foqra District, or other poor areas. There weren’t a lot of soldiers, but as soon as one was killed or seriously wounded, the replacement… it looked just like the person, knew the person’s memories, but…”

“They weren’t the same.” I’m not speaking about the soldiers.

“No. None of them were ever the same.”

We’re silent for a long time after this.

“Is that what happened to my mother?” I ask in a very soft voice. “Did she die? Was she replaced with… that?”

“I’m not sure,” Jack says again.

And then, because I can’t help myself, I say, “Is that what happened to me? Is that why I can’t remember you?”

Jack doesn’t answer.

The corpses around us wait for us to speak again.

“Here’s what I know,” Jack says finally, his low voice a rumble among the bones. “All the ones who died and came back—they were fundamentally different. Some memories were there, most weren’t. They were

extremely

patriotic. They were blindly obedient to superiors. They had no emotional attachments—to anyone. They weren’t themselves.”

Jack turns, looking me in the eyes. “But you’re still you, Ella,” he tells me, sincerity ringing in his voice. “You’re just missing one piece.”

“You.”

“But everything else is there. Your memories of me didn’t define who you were. Who you are. You’re still you, whole and complete, and everything that made you

you

is still there.”

And I wonder if he means,

everything that made me love you is still there

. But those are words that cannot be spoken, not here, not now, not by this version of me that doesn’t know that version of him.

“Am I human?” I ask, my eyes drifting to Jack’s bag, and the nanobot analyzer that told him how much of me is microscopic robots. This is not a fear I have quite been able to voice yet, but it is the deepest terror within me. I grew up in a world where things can look human but aren’t, but I have never once questioned my own humanity. It was just so clear that androids weren’t anything more than dressed-up robots. But seeing Akilah and the doppelganger for Mom, seeing my own super-human abilities… I’m questioning everything, starting with myself.

“You’re

you

,” Jack says, but I notice that this doesn’t really answer my question.

forty-nine

Jack stands, then offers me a hand to pull me up. “Ready to go?”

I stare around at the skeletons littering the catacombs. “Is this what you meant?” I ask. “When you told Julie we were going to sleep? You always meant to come this way?”

Jack stares at me, his face flickering in shadow from the flashlight. “Yes,” he says. “And now it’s time for us to stay awake.”

“Where’s that?”

Jack tries to smile. “You’ll see.”

“And you told Julie and Xavier to take Akilah and go to war…”

Jack heads toward the far side of the catacombs, and another set of stairs. “There’s an old World War II bunker on Gozo—the tunnel cuts back around, and they can get there and then to a safe house.”

I follow him up a set of stairs—old, but more modern than the ones in the secret tunnel. A wooden handrail used to exist, but it’s nothing more than rotting splinters now.

“Why did you separate us?” I ask.

“What?” Jack calls back down.

I speak up. “Why did we have to split up?”

Jack pauses for a moment, but doesn’t turn around. “I wasn’t sure it was safe.”

“I don’t care if it was dangerous—I could have gone with Akilah. Even if she’s… different… I’d rather be with her than not.”

Jack still doesn’t turn to face me when he says, “I thought it wouldn’t be safe for them.”

I stumble on the steps. My nanobot count, the tracker bots that were inside of me, my inhuman abilities… I don’t know if I can’t be trusted because of what I am or because he doubts what side I’m on, but at the end of the day—I’m a liability.

Jack opens a door at the top of the stairs, kicking against it when it sticks. We step out into the cool night air. I drink in the fresh air, filling my lungs until they ache and sighing the air out in one long whoosh.

Stars twinkle overhead, barely visible. I can see the lights of the city of Mdina nearby, so bright that they wash out the sky. We’re in Rabat, and while we’ve just emerged into a fairly large town, no one notices us. People keep to themselves here. I lived in Rabat with Mom and Dad before Mom developed the technology for the Reverie Mental Spa, and we had a small house with ivy and dusty limestone walls. This part of Rabat, however, is desolate. A few children race by, one on a bicycle, lugging a heavy cart behind him. Although they’re young, these children are working, not playing, and the curve of their backs and the cracks in their hands imply that they’re already far older than their ages allow.

In the distance, I can see the outline of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the namesake of the catacombs. Its roof is caved in, the sign is broken, the big door in the front is missing, exposing a shadowy, bare inside.

The UC never banned religion, not like some of the Secessionary States did. It just engendered apathy. Rather than actively discouraging people to drop their religion, the government simply ignored it. Holidays were changed from religious memorials to festas and parties. Tax exemptions were eliminated; no special allowances were given to any religion. When a religious statue was damaged or broken, it wasn’t repaired—it was replaced with something different, something neutral.

It wasn’t that the government made the people give up church; it’s that the people simply forgot to care. When Mom was first diagnosed with Hebb’s Disease, I caught her praying. I guess it’s only natural to pray at a time like that. But we both were embarrassed, as if I’d seen her naked, and I’ve never known her to pray since.

There are still a few cathedrals and churches scattered across Malta—St. John’s always has a big charity drive for the Foqra District every year—but for the most part, people don’t bother. I’ve never really cared about religion one way or another—neither of my parents were deeply religious, although Akilah’s family was—but seeing the hollow remains of St. Paul’s Cathedral, especially after stepping out of the catacombs filled with its own remains, makes me a little sad.