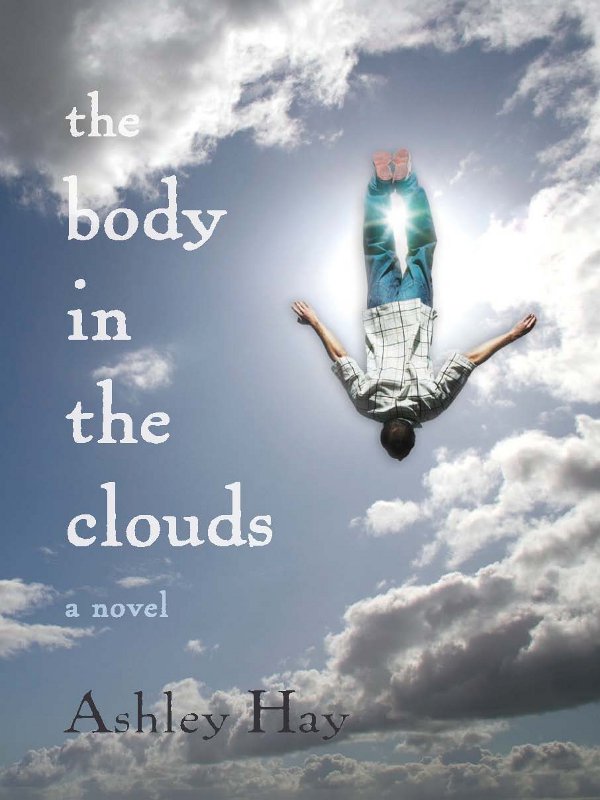

The Body in the Clouds

the

body

in

the

clouds

Ashley Hay is the author of four books of non-fictionâ

The Secret: The strange marriage of Annabella Milbanke and Lord Byron

and

Gum: The story of eucalypts and their champions

, and

Herbarium

and

Museum

with the visual artist Robyn Stacey. A former literary editor of

The Bulletin

, her essays and short stories have also appeared in anthologies and journals, including

Brothers and Sisters

,

The Monthly

,

Heat

and

The Griffith Review

.

The Body in the Clouds

is her first novel.

the

body

in

the

clouds

Ashley Hay

First published in 2010

Copyright © Ashley Hay 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: Â Â (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: Â Â (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: Â Â [email protected]

Web: Â Â

www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 242 6

Set in 11.5/16.5 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper in this book is FSC certified.

FSC promotes environmentally responsible,

socially beneficial and economically viable

management of the world's forests.

For Les and Marilyn Hay

. . . In Breughel's

Icarus

, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely

. . . the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

W.H. Auden, âMusée des Beaux Arts'

. . .That they have some idea of a future state appears from their belief in spirits, and from saying that the bones of the dead are in the graves, but the body in the clouds: and the question has been asked, do the white men go thither?

Governor Arthur Phillip to Lord Sydney, 13 February 1790

Contents

F

rom above, from some angles, it looked like a dance. There were men, machines and great lengths of steel, and they moved in together, taking hold of each other and fanning out in a particular series of steps and gestures. The painters swept their grey brushes across red surfaces. The cookers tossed the bright sparks of hot rivets across the air in underarm arcs. The boilermakers bent to the force of their air guns, rivets pounding into holes, and sprang back with the release of each one. The riggers stepped wide across the structure's frame, trailing a web of fixtures and sure points behind them.

From above, from some angles, it looked like a waltz, and a man might count sometimes in his head to keep his mind on the width of the steel cord on which he stood, on the kick of the air gun on which he leaned, on the strength of the join created by each hot point of metal. To keep his mind off how far he stood above the earth's surface. One, two, three; one, two, threeâthere was a rhythm to it, and a grace. They were dancing a bridge into being, counting it out across the air.

Halfway through a day; brace, two, three; punch, two, three; ease, two, three; bend, two, three; and it was coming up to midday. It was one way to keep your concentration. Here was the rivet, into the hole, a mate holding it in position, the gun ready, the rivet fixed, the job marked off. And again.

Brace, punch, ease, bendâthe triple beat beneath each action tapped itself out through your feet into the steel sometimes, and other times it faded under the percussive noise of the rest of the site.

Perhaps that was all that happened; perhaps there was a great surge of staccato from another part of the bridge and he lost his place in the rhythm. Lost his beat, lost his time. Because although he bent easily, certain of what he was doing, when he went to straighten up, his feet were no longer where they should have been, his back was no longer against the cable of rope the riggers had strung into place. When he straightened up, he was in the air, the sky above him, heavy with steel clouds, the water below, an inky blue.

He was falling towards the harbourâone, two, three.

And it was the strangest thing. Time seemed to stutter, the curl of his somersault stretched into elegance, and then the short sharp line of his plunge cut into the water. The space, too, between the sky and the small push and pull of the waves: you could almost hear its emptiness ringing, vast and elastic.

On the piece of land he liked best, the land near the bridge's south-eastern footprint, Ted Parker looked up from patting the foreman's dog and sawâ so fast, it was extraordinaryâa man turn half a somersault and drop down, down, down into the blue. The surprise of witnessing it, of turning at just the right time, of catching it, and then his head jarred back, following the water's splash almost up to the point where the fall had begun. All around, men were diving inâfrom the northern side, from the barge where Ted should have been working, from the southern side where he stood.

In they went, and down, and here was the fallen man, coming up between their splashing and diving. The top of his head broke through the water and the miracle of it: he was alive.

Along the site, men had stopped and turned, staring and waiting. On the water, people bunched at the bow rails of ferries and boats; a flutter of white caught Ted's eye and was a woman's white-gloved hands coming up to her mouth, dropping down to clutch the rail, coming up to her mouth again. He could almost hear her gasp. And it seemed that he could see clear across the neck of the harbour, too, and into the fellow's eyesâso blue; Ted was sure he could see themâblue and clear and wide, as if they'd seen a different world of time and place.

He thought:

What is this?

He thought:

What is happening here?

And he felt his chest tighten in a strange knot of exhilaration, and wonder, and something oddly calmâlike satisfaction, like familiarity.

At his knee, he felt the butt of a furry head as the dog he'd been patting pushed hard against him.

âYou're all right, Jacko,' he said, turning the softness of its ears between his fingers. âJust a bit of a slip somewhere.'

A

t the height of summer, the ocean a rich blue under a rich blue sky, King George III's eleven British ships ploughed one last path. Leaving the disappointment of Botany Bayâwhere was the fresh water they'd been promised; where was the grass?âthey passed two unexpectedly arrived French ships, and turned north along a coast with rose-gold sandstone cliffs, high dunes and scrubby heathland. Four leagues on, they turned inland, catching at the hidden entrance of a new harbour and sailing into the body of the land itself. It was the southern summer of 1788, and they had disappeared from any place that existed on any Admiralty map. The ships slid silently into this New Holland, this New South Wales; their passengers wondered what might happen next.

Before this, the only white that had glanced at the blue of this harbour, the blue of this sky, had come from clouds, from flowers, from feathers. Now a procession of chalk-sailed boats moved slowly westward, quite small against the size of the shore, the trees, the rocks. From above, they were scrubbed lozenges of wood topped with squares of canvas pinned and floating. From below, they were dark oblongs, obscuring some of the light, the sky, the day. From the cove where they anchored, they were a new world, tacking and curving. The flour, the blankets, the piano, the plants, the panes of glass, the reams of paper, the handcuffs and the hundred pairs of scissors in their holdsâwhat they held of these things was all there was of them here.

Their cargo included a thousand-odd peopleâsome two hundred marines and officers to take care of some seven hundred convicts; an even five dozen officers' wives and children. And this augmented by an ark of five hundred animals. They were here to establish a colony, an outpost of the British Empire. They were here to establish a prison, an outpost of Newgate, of the King's Bench. So far away, they were here to settle the mythical antipodes, literally out of the worldâas the old sailors said of such low southern voyages. They were here, on the whole, to either guard, or be guarded.

But one manâtwenty-four-year-old Second Lieutenant William Dawes from Portsmouthâhad plans beyond that. Championed by the Astronomer Royal, William Dawes had also been dispatched to scan the skies and the stars, to look for a comet. Praised for a facility for languages and natural history, William Dawes aspired to astronomy, to botany, to meteorology and cartography. He wanted to know what was here. He wanted to see everything. He wanted to learn new stories.