The Bolter (18 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

EUAN RETURNED FROM HIS BEST MAN’S

dinner with Stewart, Avie, and Muriel just after eleven. Idina, too, had returned from dinner, dressed to the nines. She’d had time to have a drink or two. Euan had too.

He tried to persuade her to stay: “Long talk to Dina …”

Euan had some strong points to make. For one, Idina would lose any right to the money in the Marriage Trust. Her mother was still emptying her own bank account into the Socialists’ and Theosophists’ pockets. Charles Gordon couldn’t have much left to rub together. That meant no Lanvin, no Claridge’s, no Ritz. If Idina insisted upon going, she would be giving up a fortune.

But Idina clearly didn’t give a damn about money. She wouldn’t have been leaving Euan if she had. In any case, she had a little money in her own right. It wasn’t a fortune, but if she went abroad it would be enough to live on.

The children were more difficult. Euan was, after all, the one with the money to support them and give them the best lives they could have. Besides, no gentleman wanted his children living in another man’s house. Even if he had seen them just twice in the past twelve months, he certainly was not going to allow Idina to take them to Africa. What they needed was an English education. In any case, before they could blink the boys would be seven and off to boarding school. What would either see of them then?

For the past four years and a bit, the major part of their short pre–boarding school life at home, Idina had been the one making sure the children were well, taking them to the doctor, taking them to the seaside, finding somewhere for them to live when fevers struck and bombs fell, hiring and firing nannies, nursery maids, and cooks. She had done all that she was expected to do as an Edwardian mother. Yet, if she refused to leave them with Euan, he could refuse the divorce. And, as he had not in fact deserted her, Idina would have been extremely unlikely to win a divorce from him. An unhappy mother was not a good mother. Idina herself had grown up with only one preoccupied parent and Rowie, her divinity of a governess. It had seemed, happily, to be quite enough. Her mother was still at Old Lodge, as was Rowie, to keep an eye on things. And, now that the war was over, they would have Euan. When he was there he was very good with them. Africa, on the other

hand, was not a place for children. As painful as it might be, giving her boys to Euan clearly seemed the best thing for them.

But Euan didn’t just want the children to stay with him. He didn’t want any coming and going. What they needed was stability. If Idina insisted upon leaving with Gordon, she would have to go and never return. She couldn’t hop in and out of their lives on a whim.

The alternative to all this was to find a way to make their marriage work again.

Emotions deepen late at night. And it was “far into the night” by now.

Idina softened into indecision.

Their conversation was not over. Idina had been certain but now, seeing Euan again, she was not so sure. She had fallen in love with Charles and therefore believed she ought to marry him. But she still loved Euan too.

10

The sky outside was late-autumn pitch.

It was not an hour to make promises that might be hard to keep.

IDINA SPENT THE NEXT DAY

with her friend Eva. The moment Euan had left to grip his mother’s shoulders while she wrung her hands with all the agony of a soothsayer ignored at the prospect of her adored son being tarnished with a divorce, Idina had called Eva, who had come round. The two women had talked all morning. Then, when Euan returned, they went out to lunch—Euan gave them a lift—and talked some more.

That night, when Euan returned from another pre-wedding dinner followed by a show with Avie, Idina was waiting for him again. “Another talk to Dina lasting two and a half hours.”

Even though Idina had conducted her affair with Charles so publicly, as good as living with the man, Euan was prepared to have her back on a sole condition—that she never saw Gordon again. If she did, he would divorce her and she would never see the children.

It was a big promise to ask Idina to make. Euan gave her two weeks to decide.

The next morning Euan went to his lawyers, Williams and James, “eliciting a great deal of information about the general position.” He could start divorce proceedings against Idina in Scotland, as far as possible from the Fleet Street press. A single hearing, a couple of witnesses, was enough.

He then went shopping, eventually returning to Connaught Place to talk to Idina for half an hour before a lunch party at Dorchester House.

Behaving as though he thought his threats might work and Idina would be coming back to him, he returned “home at three and picked up Dina and drove her to Victoria in the little car,” her own car, gas bag still teetering on top. He pulled up outside and called a porter for her bags.

They stood facing each other, the train whistles filling the space between them. The station was heaving, every step across the concourse blocked by muted tweed, worn leather and khaki still bobbing around. The air stank. Coal, grease, shoe polish, unfinished sandwiches, half-digested meat pies, and human sweat were being steamed up to the top of the high glass arches, where they condensed against the freezing air outside and fell back in erratic, noxious droplets.

They said good-bye. Idina swung on her heels and tripped off in the direction of the Brighton train.

Through the smoke, Euan could see Rosita Forbes waiting on the platform.

Chapter 12

I

dina’s two weeks to decide slid through her fingers. She left Euan on Friday, 22 November. Five days later she sneaked up to London on the day before Avie’s wedding to see her mother and sister. She admired Avie’s dress, examined the wedding presents on display, and slipped away back to Brighton. She would not be returning the next day. A sister who had just left her husband—particularly when he was the best man—was not auspicious at a wedding.

As Idina retreated from her own family, Euan slipped further into its bosom. An hour after Idina had gone he arrived for the bride’s “reception to view presents.”

1

He took Stewart out to the Ritz and then went straight on to the Albert Hall, where a Victory Ball was being held and where he had a rendezvous with the chief bridesmaid for the next day—Dickie. They danced until two-thirty in the morning.

Twelve hours later Euan was best man at Idina’s sister’s wedding. The two celebrations could not have been more different. While Idina and Euan had wed in a tiny church tucked away in a Mayfair back street, the church in which Avie and Stewart had chosen to marry, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, towered over the northeastern corner of Trafalgar Square. The pews were packed and the central aisle was lined on each side by men of the 2nd Life Guards. Just after two-thirty in the afternoon Avie appeared. Idina had worn a traditional traveling dress in which to leap on a train and vanish on honeymoon. Avie wore a silver-and-white brocade, medieval-style gown. She wore a wreath of orange blossom over

her veil and carried a bouquet of mauve orchids. Beside her walked Buck, his able seaman’s uniform aggressively plain against the red and gold of the Cavalry officers and troopers lining the center aisle. Then came Dickie and four others dressed in “ruby chiffon velvet with bronze Dutch caps and gold shoes.”

2

They were also carrying orchids—an even more colorful combination of red, white, and purple. “Felt rather like crying,” wrote Euan. That night he cohosted a dance “to console the bridesmaids.” He again stayed until two-thirty in the morning, when he took Dickie home. Two weeks later, Idina’s deadline passed. Euan was back at Idina’s mother’s house, Old Lodge: “am Stewart and Ave’s first guest, apart from my own children, who are here permanently,” he wrote. Stewart and Avie’s second guest was Dickie. And within a day of returning from this pleasant foursome weekend, Euan had instructed his solicitors to file for divorce in Scotland.

The following weekend he again visited David and Gee at Old Lodge, where he had “a strenuous time playing ‘bears’ with the children.” On Sunday, Buck set off to see Idina in Brighton. Euan was willing, even now, to stop the divorce. But Buck “came back at 7:15 with no news.” Idina had still not made up her mind.

Late the next evening she rang Euan in London. He had come back to Connaught Place with Stewart, Avie, and Dickie after the theater. The four of them were drinking, dancing, chatting about the play they had seen. But it was to Stewart that Idina spoke on the telephone; she would, she said, meet him for lunch at the Ritz the following day.

Whereas the Ritz in Paris slithered back in long passageways from a snippet of the Place Vendôme, the London Ritz was, and still is, a palace stretching an entire block along Piccadilly at the corner of Green Park. That day its cavernous atria echoed with jangling chandeliers, their lights reflecting off mirrors and white walls. Even in December the dining room was light and airy, overlooking the manicured lawns and almost neatly leafless trees in the park below. Idina sat across the table from Stewart. Fifteen months earlier they had been sharing a table at the Ritz in Paris. There had still been a war on. She and Euan had still had a marriage.

Had it been the war that had worn away their marriage? So much of their time had been spent apart, neither of them sure whether they would see the other again. Even their times together had been abnormal, driven by a frenzied obligation to enjoy themselves as much as they could. Perhaps they had forgotten how to be married in any other way.

From Idina’s twenty-five-year-old perspective her marriage to Euan

was not recoverable. She was not coming back. She was, she told Stewart, going to move on and make herself a new life instead.

3

She stood up, the folds of her day dress shimmying around her, kissed Stewart good-bye, and left.

Euan had been lunching at White’s Club, just around the corner from the Ritz and close enough for Stewart to call in were he to effect a reconciliation. After Idina left, Stewart called for him. Euan strode over. Stewart was brief. There was not much he could say. After a short while Euan returned to Connaught Place, where he spent “the rest of the day completing packing and moving kit to Grosvenor Street, paying off servants, etc.” His life in Connaught Place was over. Euan was moving into the same street as his mother.

Two days after this, following a large dinner at the Ritz and the usual play, Euan and Barbie slipped away together alone. “Went to Combes’ dance.” They stayed two hours. “We just danced together all the time.” Long, lean, beautiful Barbie, swinging around him, curling up on his shoulder.

Poor Dickie was ill at home in bed.

ON SATURDAY, 1 MARCH 1919

, Euan walked from Edinburgh’s New Club, where he had stayed the night before, to the Court of Sessions with his solicitor. His petition for divorce was second on the court list. At ten-thirty he was called into the witness box. The questions were short. Within less than half an hour both he and two witnesses had given evidence and the presiding judge, Lord Blackburn, had stopped the case and granted Euan his divorce.

Twenty-four hours later, back in London, Euan collapsed with a soaring temperature. “Teddie came round to see me and said I had got flu.” Over the past twelve months Spanish flu had killed twenty-five million people around the world, a quarter of a million of them in Britain. “No visitors allowed.” It took him two long, lonely days to decide to see a doctor, who then told him that the tonsillectomy he had had five years earlier was “badly bungled and my septic tonsils have grown again rather worse than before.” Euan needed another operation but at least he could have visitors.

Barbie was the first to arrive.

It would be two weeks at least before the infection had subsided enough to make it possible to operate. Euan’s throat was on fire, his temperature pistoned up and down. He couldn’t go out of the house and, when friends came to visit him, which they did in droves, he could

barely talk. After a week he was allowed to be driven down to Old Lodge to see the children, as it was now his responsibility to do. Gerard, now three and a half, had an infernal cough and it dawned upon Euan that, however ill he himself might feel, if he didn’t arrange for his son to see a doctor, nobody else would.

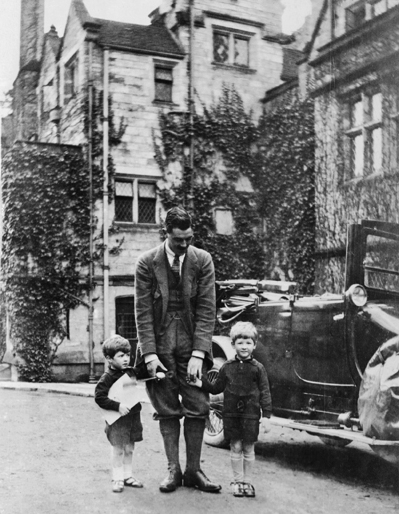

Euan and his sons after Idina’s departure, Old Lodge, April 1919

Euan summoned the grandest doctor he could find for Gerard, then, having had the remains of his tonsils dug out, decided to go abroad himself. It was customary, having been involved in a scandal, to vanish for twelve months. Stewart had offered him a job in America as part of an ambassadorial mission from the then secretary of state for war, Winston

Churchill. The aim of the mission was to establish an alliance between Britain, France, and America. The political advantages of such a relationship were to be presented by the former foreign secretary Lord Reading. The military point of view would be put forward by the war veteran and general Sir Hugh Keppel Bethell. Euan was to propose that Britain and America should exchange intelligence and counterespionage information. He drove down to Eastbourne, found the boys some lodgings by the sea, hired a governess to look after them, not Idina’s Rowie but a Miss Jeffreys, and left for America for a year.