The Bolter (9 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

The first task in this great project was, as these plans were being drawn up, discussed, and redrawn, to take down the old house. In the

spring of 1914, as the thick layer of winter snow cleared, the tiles were pulled off the roof of Old Kildonan.

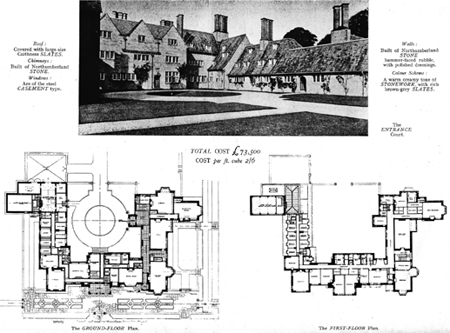

Kildonan House, Ayrshire: the home that Idina designed for her life with Euan and their children. She worked on the plans but never saw the house completed

.

IDINA NOW HAD EVERYTHING

in place for a magnificent life. She, Little One, had the Brownie she loved, and soon they would have a child. Euan had embedded himself at the heart of Idina’s family. He popped in and out of their houses alone, and had become an elder brother to the fatherless Avie

12

and Buck. The Sackvilles and Brasseys in turn spun in and out of Connaught Place.

Meanwhile, together, Euan and Idina were one of the most sought-after couples in town. He was rich and handsome, she was glamorous and daring. They were invited out in several directions each night. They were building a vast home that epitomized the Edwardian country-house dream. The only financial worry they might ever have would be that they had too much money rather than too little. And once they had

had a couple of children they would be able to spend that money traveling the world in limitless adventures. For a girl who had been shunned by society as a child, it was almost too good to be true.

Until the new house was built, Idina and Euan entertained their friends in London. When Euan returned from watching saddles being soaped, stirrups polished, and swords sharpened at Windsor, Idina welcomed him to a drawing room overflowing with young people. Their unmarried friends still lived with their parents. Idina and Euan’s house, however, was gloriously free of any parents at all. It was spacious, rule-free, and had endless supplies of food and drink being produced by innumerable staff, together with the very latest gramophone records. Night after night Idina and Euan dined in a great gang at the Ritz, the Carlton, or Claridge’s, went to the latest show, and then returned to Connaught Place. There their friends and Idina’s younger sister, Avie—just seventeen and so almost “out” in society—sang and listened to ragtime and blues until the early hours, perfecting their steps in the shockingly intimate tango or the latest “animal” dance from the United States, inevitably popularized by being denounced by the Vatican. They ground their bodies against one another in the Bunny Hug; hopped and scissor-stepped in the Turkey Trot; yelled, “It’s a bear!” as they swayed to the Grizzly. And, as spring turned into summer, the new Fox-trot arrived from across the Atlantic.

But, on 28 June, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated in the Serbian city of Sarajevo. Within a few weeks the world was at war.

For a young Cavalry officer, it promised to be a glorious chance of an adrenaline-fueled charge for King and Country, followed by a glorious return to the stately life Euan and Idina were constructing. As war was declared, a line of twenty horse-drawn carts laden with stone were on their way from the station at Barrhill to the Kildonan building site.

13

But, by the time the war had ended, and the house had been built, both the world they were building it for—and Idina and Euan themselves—would have changed irrevocably.

Chapter 4

O

n 14 August 1914 Idina watched a single squadron of the 2nd Life Guards line up two abreast along an avenue running north-south just inside the eastern edge of Hyde Park. They wore their modern Cavalry uniform of khaki, only distinguished from foot soldiers by the leather of the cross belts that lay diagonally over their chests, broadening their shoulders.

As the band struck up and Euan and his fellow officers moved off, rows of women lining the route in white dresses raised their arms and voices in euphoric excitement. Those chaps on horses, it was being whispered, were the lucky ones, the ones chosen to go to France. They had a chance of seeing the first action since the Boer War, which they had followed as short-trousered schoolboys. This was a token land force going over. Britain’s great strength, where surely it would flex its muscles in the fight to come, was at sea. In any case, it wouldn’t go on for long. The last war on the European mainland had been between France and Prussia more than four decades ago. It had lasted a year. The word on the street was that this one would be “over by Christmas.”

The word being muttered along the corridors of power, however, was a little different. There the extravagantly moustached Lord Kitchener, victorious veteran of the fight against the Boers and Field Marshal of the British forces worldwide, thought it might last a little longer. He took as his example not the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, which he had joined as a field ambulance volunteer, but the slightly earlier

American Civil War. That had lasted four years and taken the lives of more than six hundred thousand men. In August 1914 Kitchener was already forecasting that this new European war would last three.

Euan left with the single “composite” Household Cavalry regiment—made up of a squadron of each of the two Life Guards regiments and one from the Blues—as railway stations throughout Britain filled with man-boys slouching on kit bags, knocking their heels against the canvas as they smoked and nodded, wondering whether they, in the glorious adventure that awaited them, would prove themselves to be men.

And the men and women they left behind in England went to war on the Home Front. On 8 August the Defence of the Realm Act had come into force, giving the government powers to commandeer economic resources, imprison without trial, and exercise widespread censorship. The streets of London were flooded with families of Belgian refugees: young children and their gray-clad parents, their heads low, dragging suitcases behind them. Lord Kitchener’s famous finger-pointing poster “Your Country Needs You” appeared up and down the country, drumming up vast numbers of volunteers, who were being marched to and fro through London’s parks until enough uniforms and rifles could be found for them. A handful of duchesses and countesses were setting up their own Red Cross hospitals to take to the Front. Nursing was the grandest way for a lady to help the war effort. But the young Lady Diana Manners, the famously beautiful and daring daughter of the Duke of Rutland, and a contemporary of Idina’s, found herself forbidden to race across the Channel too, lest “wounded soldiers, so long starved of women, inflamed with wine and battle, ravish and leave half-dead the young nurses who only wish to tend them.”

1

Idina, eight months pregnant, could do none of these things. Instead she moved back into her grandfather’s house in Park Lane, where the extended family had gathered both themselves and what food supplies they could, to await the birth of her child.

For the next few weeks news of skirmishes, parries, and victories seeped back to London: first in the news posters plastered around the city and soon afterward through the details written up in the newspapers. Although the British Cavalry had discarded the old-fashioned armor and costumes still worn by their French and German counterparts, they were nonetheless mounting charges, one Cavalry officer writing that even his “old cutting sword… well sharpened… went in and out of the German like a pat of butter.”

2

In the first week of September

the Allies counterattacked at the River Marne and stopped the German advance, but the British Expeditionary Force, a tiny army compared with the million Frenchmen and million and a half Germans, was severely weakened. The BEF was left holding a thin line, unsupported from behind and desperately awaiting reinforcements before the Wagnerian wrath of “the Hun” reached them. Just as the news came back that the Cavalry had dismounted and were fighting alongside the infantry in the trenches, the dreaded telegram boy rang the bell at 24 Park Lane.

Idina’s cousin Gerard had been killed. He had been fighting in a battle at the River Aisne in northern France. Like Euan a lieutenant, he had been in the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards. This infantry unit had been engaged in heavy fighting both in the trenches and on open ground—with fatal results.

For Idina this was deeply upsetting news and almost certainly the first big shock of the war. She was resolved that if she had the opportunity she would name a child after him.

Just a fortnight later, on 3 October, Idina’s baby was born at 24 Park Lane. It was a boy. However, when, a few days afterward, she received the inevitable elated letter from her husband, the news cannot have been entirely encouraging. Euan had been putting his own life at risk so often that his commanding officer had told him that he was being “Mentioned in Dispatches”—mentioned by name in one of the Commander in Chief’s reports back to Kitchener, the recently appointed Secretary of State for War. It was the lowest military recognition for bravery but it was still a tempting first step toward a medal for some daring act.

Euan also wanted his new son, as the eldest Wallace male in his generation, to have a Wallace name. He wanted to name him, as he himself had been named, after his father and grandfather, and father and grandfather before that. Euan’s first name was David, and Euan was a Scots variant of his father’s name, John. And now that the Wallaces had—sporting seasons aside—come south, John it would be. David John. Nor would they have any of that now passé fin-de-siècle fashion for children being called by their second name. Finally, in order to firmly entrench his son in the bosom of English society, his name should be put down for Eton, where Idina’s brother, Buck, had just started school. It would take Idina another son to have the name she wanted.

A little over a week after this, it was Idina’s turn to receive a telegram.

Euan had been manning one of the outposts at Warneton in Belgium, ahead of the main line. Sheltered as the spot was within the undulations of the cloud-hung Flemish hills, the morning of 20 October began quietly, promising another hour-counting game of sitting, watching, waiting. When Euan levered himself out of his bunk, he had a chance to feel the length to which his stubble had grown, and settle down to breakfast.

At 0800 hours the silence exploded—and a piece of shrapnel embedded itself in Euan’s leg. Behind the shells twenty-four thousand German riflemen and four motorized Jäger divisions were advancing toward him. Within seconds Euan was soaked in his own blood. He had a pearly-white bleeder’s skin; knock it and a great bruise would spread.

3

But, at least at this moment of his not very long life, he was lucky. The stretcher-bearers strapped him into one of their stained, sagging canvases and started to bump him back, slipping and skidding again and again in the knee-deep mud. From time to time, between the stinking dark-gray clouds of smoke and flesh and the wobbling sky above, the clenched jaw of one of the bearers would swing into view, a vial of morphine hanging from his shoulder. If Euan had been in too many pieces to cobble back together in a stretcher, the bearers would have simply given him as much of it as they could spare.

The stretcher-bearers took him to the Regimental Aid Post, a muddy, bloody, rainy sprawl of bodies around a single tent, a good number of them in no state to go any further: some calling for their mothers; others begging “for the love of God” to be shot. The Post had been packing up, or trying to pack up, and move back toward Ypres in a general retreat, but men were still being tipped out onto the ground around it left, right, and center.

“What’s his trouble?” was the medics’ question.

“Leg, shrapnel,” came the reply.

And then they had lifted him out onto a ground sheet and, within a couple of seconds, had turned and gone back for another.

Before the Germans reached the Aid Post, Euan had been moved back, via the Advanced Dressing Station, to the Casualty Clearing Station. There his wound was judged severe enough for him to be sent back to England. Three days after he had first been wounded, Euan reached England on a hospital ship and was transferred to the barracks hospital at Windsor.

4

Although in what must have been severe pain, he was nonetheless fortunate. He had been hit in the initial few days of the long First Battle of Ypres, before all those posts and stations and tents

had become clogged with the tens of thousands of mutilated bodies that followed him. And he had escaped the trenches. Not all the lieutenants in the 2nd Life Guards had.

By mid-November five of the regiment’s officers had been killed. Seven, including Euan, had been wounded. Eight were missing, of whom only one would turn out to be alive, and two had been sent home sick from France. Only six out of the total of twenty-eight 2nd Life Guards officers who had been sent to the Front remained there. More broadly, the British Army, which had set off to certain, glorious victory, had been all but destroyed. A month later Euan, still convalescing but looking fit enough to return to France soon, was promoted to captain to fill a gap.