The Bone Labyrinth (19 page)

Read The Bone Labyrinth Online

Authors: James Rollins

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Thriller & Suspense, #War & Military, #United States, #Thrillers & Suspense, #Military, #Suspense, #Thriller, #Contemporary Fiction, #Thrillers

Roland’s words grew somber with respect. “Father Kircher was considered by many to be the Leonardo da Vinci of his time. He was a true Renaissance man, with a keen interest in many disciplines: biology, medicine, geology, cartography, optics, even engineering. But one of his greatest fascinations was languages. He was the first to realize that there was a direct correlation between ancient Egyptian and the modern Coptic languages used today. For many scholars, Athanasius Kircher was the true founder of Egyptology. In fact, he produced great volumes of work regarding Egyptian hieroglyphics. He came later in life to believe they were the lost language of Adam and Eve and even undertook to carve his own hieroglyphics into a handful of Egyptian obelisks that can be found in Rome.”

Gray’s interest in the man sharpened. He studied the countenance, those thoughtful eyes, flashing back for a moment to his old friend Monsignor Vigor Verona. The two men, though they lived centuries apart, could have been brothers—and perhaps in some respect they were. Both were men of the cloth who sought to understand God’s creation not solely through the pages of the Bible but through exploration of the natural world.

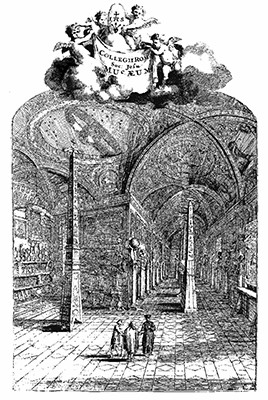

Roland continued, “Father Kircher eventually founded a museum at the Vatican college where he taught and studied. The Museum Kircherianum contained a colossal collection of antiquities, along with a vast library and several of his own inventions. To give you some scope of that place—and of the man’s significance to his time—here’s an etching of that museum.”

Roland returned to his manila folder and slid out another picture.

Gray examined the depiction of that cavernous domed space, all housing the life’s work of one man. He had to admit it did look impressive.

Seichan appeared less stirred. “So how did this Jesuit priest end up in the remote mountains of Croatia?”

Roland gave a small shake of his head. “Actually no one knew he had been up there. From my own doctoral research into Father Kircher’s history, he arrived in our city in the spring of 1669 to oversee the fortifications of Zagreb Cathedral.”

Gray remembered spotting the towering Gothic steeples of that cathedral on their ride into town. They were impossible to miss, as they were the tallest structures of the city.

“Because of the ongoing Ottoman threat during that time,” Roland explained, “massive walls had been built around the cathedral. Father Kircher had been personally summoned by the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold I, to help with the engineering of a watchtower along the southern side, intended as a military observation post. But during my research, I found inconsistencies with this story, evidence that the reverend father went missing for weeks at a time while working here. Rumors were rife among the local townspeople that Kircher might have been called by the emperor for some other purpose, that his involvement with the watchtower was merely a story to cover up some ulterior motive.”

“A motive that might not be secret any longer,” Gray said, nodding to the journal. “But even if someone found that cavern full of bones and paintings, why would the emperor call for Father Kircher to investigate?”

“I can’t say for certain, but the reverend father was known for his interest in fossils and the bones of ancient people.” Roland continued to explain as he scanned through several pages of his copy of

Mundus Subterraneus

. “This work by Father Kircher covers every facet of the earth—from geology and geography to chemistry and physics. Inspiration for this undertaking came when Father Kircher visited Mount Vesuvius, just after it erupted in 1637. He even used ropes to lower himself into the smoking crater to further his understanding of volcanism.”

The guy definitely put himself into his work,

Gray had to admit.

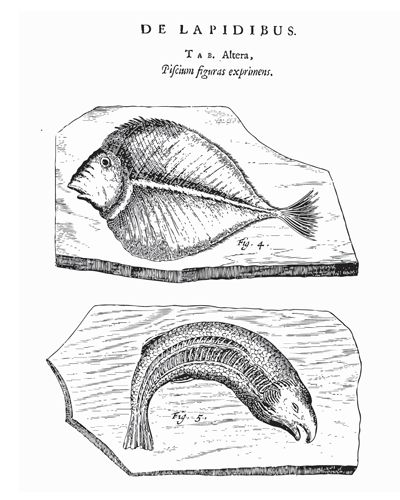

“Father Kircher came to believe the earth was riddled by a vast network of underground tunnels, springs, and ocean-size reservoirs. While searching this subterranean world, he also collected thousands of fossils and documented what he found.”

Roland stopped on a page showing the renderings of fossilized fish.

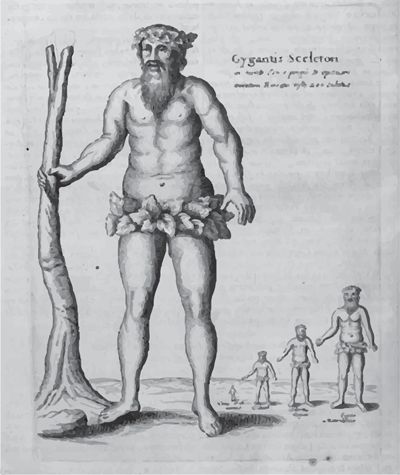

“There are pages and pages of such drawings in here,” Roland added. “But Father Kircher also discovered caves in northern Italy that held massive bones. They were the leg bones of mammoths, but he mistakenly attributed them to a species of giants that roamed the earth alongside early man.”

Roland flipped to a page showing Kircher’s attempt to capture what these mythical giants might look like and their relation in size to regular men.

Roland must have read the amused skepticism on their faces and matched it with a small smile. “Admittedly the reverend father did come to some strange conclusions, but you must understand he was a man of his time, trying to understand the world with the tools and knowledge of that era.

Mundus Subterraneus

contains many such whimsical speculations, from ancient monsters even to the location of the lost continent of Atlantis.”

Gray straightened and stretched a kink from his back after leaning over the table for so long. He was losing patience. “What does any of this have to do with resolving the mystery of that cavern?”

Roland looked unfazed by his challenge. “Because I know

why

Father Kircher was summoned to these mountains.”

Gray looked harder at the man, noting the return of that excited sparkle to the priest’s eyes.

Roland shifted over to grasp the metal plate resting on the table and turned it over. Its silvery surface looked freshly cleaned. “This placard was bolted to the outside wall of that cavern chapel.”

Gray noted the lines inscribed across the plate, all written in Latin, with a row of symbols along the bottom. “You were able to translate this?”

Roland nodded. “The message is mostly an admonishment against trespassing into those caves, a crime punishable by death.”

“Why?” Seichan asked. “What did they think they were protecting?”

Roland ran a thumb under one line of Latin and translated it aloud. “ ‘Here rest the bones of Adam, the father of mankind. May he never be disturbed from his eternal slumber . . .’ ” He took another breath and finished the line. “ ‘. . . lest the world come to an end.’ ”

6:14

A

.

M

.

Lena felt a prickling chill at these last words. She had also been staring at the open volume of

Mundus Subterraneus

, at the page depicting that ancient giant, while remembering the dance of shadows cast upon the cavern walls. Those dark figures had loomed large, climbing high above the herds of painted animals.

As if cast by an army of Kircher’s giants.

Gray spoke, drawing her attention away from the book. “Why would Father Kircher believe those Neanderthal bones came from Adam?”

“Clearly he was mistaken, as with the mammoth bones.” Roland shrugged. “Perhaps he came to that wild conclusion based on the extreme age of the bones. Or maybe it was something else he found. There were those strange petroglyphs, those star-shaped palm prints . . .”

He looked to Lena for support.

She shook her head, unable to offer any explanation, but it reminded her of another mystery. “What about the other set of remains, the ones that Father Kircher might have removed from the site? Did he think they belonged to Eve?”

“Possibly,” Roland admitted. “But there’s nothing written on this plate about those missing bones.”

“Assuming Kircher believed they were Eve’s remains, why would he take them?” she pressed. “Why not leave them to eternal rest like Adam?”

“I don’t know.” Roland frowned. “At least not yet.”

Seichan reached and tapped the bottom of the metal sign. “What about this line of symbols?”

Lena had noted the faded row of tiny circles, too, showing a gradation of shading along their length. “They look like the phases of the moon. See how there’s twenty-eight of them, the same number as a full lunar cycle.”

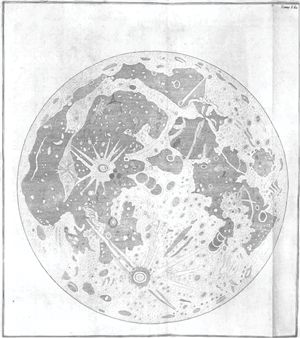

“I think Dr. Crandall is right,” Roland said. “I do know that Father Kircher became obsessed with the moon. He believed it was critical not only to the functioning of the earth—as with the ocean’s tides—but also to mankind’s existence. He used telescopes to create intricate maps of the moon, many of which you can find in

Mundus Subterraneus

.”

As if trying to prove this, Roland thumbed through several pages until he reached a hand-drawn sketch of the lunar surface.