The Bone Palace

THE

BONE PALACE

THE NECROMANCER CHRONICLES BOOK TWO

AMANDA DOWNUM

The man was good; Savedra would have to be better. She knew his path—down the arcade and up the stairs, to the glass-paned double doors that led to the prince’s suite. Or the other set that led to the princess’s. And if it were the latter, the little voice that sounded like her mother asked, why did she not merely stand aside and let the deed be done? She would be there to comfort Nikos in the morning, after all.

She moved before she had to answer the question, anger and excitement loosening stiff limbs. On the other side of the arcade, a soldier moved slower and louder. The assassin spun, blade gleaming, and gave Savedra his back.

Too easy.

The impact jolted her arm. The blade slowed on leather, quickened through flesh, then struck bone with a scrape that set her teeth on edge. She braced as the assassin’s weight leaned back against her. She might regret being born a man every time she had a gown fitted, but it meant she was stronger than she looked.

The killer cursed softly, quiet even in death, and tried to pull free. One gloved hand groped backward. Savedra twisted the knife.

Lanterns bloomed in the shadows to blind her and swords rattled. Then Captain Denaris was there, knocking the man’s weapon away, pulling him off Savedra, a soft stream of profanity fit to rust steel hissing from her lips.

“Alive! Alive, damn it! Why is that so bloody difficult? ”

To Sarah, Sonya, and Liz,

my muses for all things classical,

and to Steven, for not getting a

third-book divorce.

I am weary of days and hours,

Blown buds of barren flowers,

Desires and dreams and powers

And everything but sleep.

Algernon Charles Swinburne

—“The Garden of Proserpine”

Love is a many splintered thing

The Sisters of Mercy

—“Ribbons”

PROLOGUE

496 Ab Urbe Condita (1228 Sal Emperaturi) Three years ago

D

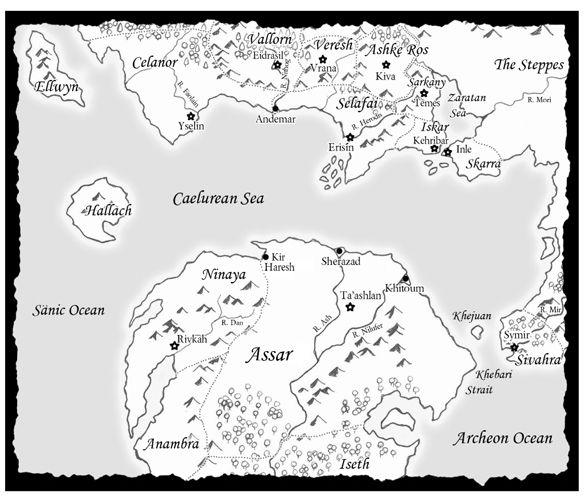

eath was no stranger in Erisín. The city named for the saint of death and built on the bones of its founders had known its share of suffering, but the pestilence that struck that summer was enough to horrify even the priests of Erishal. The plague had come from the south, borne on a merchant ship that slipped through a lax quarantine. It spread now through the bites of fleas and midges, so that any drone of wings or sudden itch meant terror. Hundreds dead throughout the city, temples and hospitals become mass tombs, and in the slums they dispensed with the proper rites altogether and stacked the infected dead like cordwood.

Not even the palace was safe.

The queen no longer trembled. She lay still now in the wide curtained bed, only the shallow rise and fall of her

breast and her fluttering lashes to show that she lived. Sweat soaked her linen shift, matted her long black hair. Brown skin flushed gold with jaundice and the whites of her half-open eyes were yellow and bloodshot.

The room stank of sick sweat and vomit, the cloying sourness of old blood. Shutters and curtains blocked the windows despite the summer heat, and lamps trickled dark malodorous smoke. Meant to keep insects at bay, but it served with men as well. Sane ones, at least.

Kirilos Orfion, spymaster of Selafai and the king’s own mage, sank into a chair and wiped his brow with a sodden cloth. A cup of tea sat on the table beside him—long cold, but it eased the ache in his throat, if not the ache in his bones. His hands shook, sloshing brown fluid over the rim. Sunken, shaken, sweating—he must look as though the fever burned in him too.

Boots rang heavy in the hall outside. Mathiros keeping vigil. The king hadn’t slept since his wife took ill, save in fitful snatches beside her bed. Kiril had finally sent their son to rest with a whispered spell, but it was all he could do to keep Mathiros from the room. It was all he could do to keep death from the room. He rarely wasted energy on regret and might-have-beens, but now he wished for the healing skill he’d abandoned so many years ago. In his decades of service to the Crown he had known worry and fear and even the sharp edge of panic, but never this sick helplessness.

Kiril felt Isyllt waiting beyond the door as well, tasted her own fatigue and worry. Ten years as master and apprentice and two as lovers had left their magic inextricably twined—even now she reached for him, a soft

otherwise

touch, but he drew away, tightening his mind against

her. She would only exhaust herself trying to comfort him and that would serve nothing. If he burned himself out here, the city would need all the mages it had left.

The fever might not be the work of spirits as the superstitious claimed, but so much suffering still attracted them. The mirrors in the room were draped with black silk, the windows warded with salt and silver, but even now something skittered over the shutters, larger than an insect. Those mages who weren’t tending the sick spent the nights hunting newly fledged demons.

He stood, wincing as his joints creaked, and limped toward the bed. “Lychandra.” His voice broke on her name, hoarse and ugly.

Bruised lids opened and golden-brown eyes met his. Lucid now, at least, delirium fled. No wonder people thought the plague demon-born, when victims died bloody and raving.

Her lips cracked as she smiled. “You’re as stubborn as Mathiros.” Her voice was soft and ragged. “Find someone else to save—it won’t be me.”

He pressed a cup of willow bark tea to her mouth. She coughed around the swallow and bloody saliva flecked her lips. The physicians had shaken their heads when she first vomited black blood, said she was beyond their skill. She was likely beyond his, too, but he had to try.

Kiril sucked in a deep breath and tried to clear his mind. The magic answered slowly, scraping like broken glass in his veins. A cool draft whipped through the room, fluttering the bed hangings and rattling the shutters. Lychandra sighed as it breathed over her skin, respite from the fever’s heat. Kiril laid a hand on her brow and she gasped.

His vision blurred and he saw with

otherwise

eyes—illness hung on her like a pall, swirled dark and yellow-green as bile inside her. Contagion flared like an asp’s hood as his magic lapped over the queen’s skin; it had feasted and grown fat in three days, while Kiril had only worn himself dry. His power broke, splintering ice needles inside his chest. He fell to his knees beside the bed, jarring bones even through thick carpets.

Lychandra turned her head and pink saliva dripped onto the sweat-stained pillow. “Kirilos—” Her long brown hand touched his, burning his numb fingers. “No more. You’ll only hurt yourself. Please, let me see my husband.”

He nodded, climbing shakily to his feet. Hard to breathe around the pain in his chest. He’d seen this woman a glowing bride, listened to her curse in childbirth. He hadn’t thought to stand her deathwatch, too. Pins and needles stung his hand as he opened the door.

The king’s face only made it worse—skin ashen, eyes black pits under his brows. Mathiros read defeat in Kiril’s expression and let out a sound neither sob nor howl. He shouldered the sorcerer aside as he rushed to his wife.

Isyllt followed the king into the room and stepped into Kiril’s arms. She cupped his face in white hands and kissed him, the familiar scent of her hair filling his nose. Her grey eyes were shadowed and dark with worry; he winced from his reflection there. So tired. So old.

“You have to rest,” she said. “You’ll kill yourself this way.”

He would die, sooner or later. Sooner every year. Leave her grieving beside his bed like Mathiros beside Lychandra. He lowered her hands away from his face. She was too young to be a widow—certainly too young to be his.

He might have told her so, but he couldn’t get enough breath. His chest ached like a bruise.

“Kiril.” Mathiros’s voice cracked on his name. “Is there nothing—Anything—” Tears soaked his beard, splashed his wife’s hand. Kiril wanted to cringe at the pain in his eyes. “You can’t do this!”

Whether he spoke to Kiril or Lychandra or Erishal herself, the sorcerer couldn’t say. His palms slicked with cold sweat and Isyllt’s hand tightened on his.