The Book of Air and Shadows (25 page)

Read The Book of Air and Shadows Online

Authors: Michael Gruber

He didn’t know how he’d end it, but the more he thought about it, about the intersection between fiction and the real, the more he thought that he had to get some advantage over Bulstrode, the Shakespeare expert, and the best way to do that was to crack the cipher, because with all his expertise, that was one thing Bulstrode did not have. So besides having to learn a lot more about Shakespeare, he had to decipher and read Bracegirdle’s spy letters. Such were Crosetti’s thoughts during the long drive back to the city, peppered by the usual fantasies: he confronts the angry husband, they fight, Crosetti wins; he finds Carolyn again, he acts wry, cool, sophisticated, he has understood all her plottings and forgives; he earns a fortune via the manuscript and explodes upon the cinematic world with a film that owes nothing to commercial demands yet touches the hearts of audiences everywhere, obviating the necessity for a long apprenticeship, cheap student films, playing gofer to some Hollywood asshole….

He arrived back in Queens at around eight on Saturday evening, fell immediately into bed, slept for twelve hours straight, and awoke vibrating with more energy than he’d felt in a long time and frustrated because it was Sunday and he would have to wait before getting started. He went to mass with his mother therefore, which pleased her a good deal, and afterward she made him a colossal breakfast, which he consumed with gratitude, thinking of the scrawny kids in that house and being frankly grateful for his family, although he knew it was totally uncool to have such thoughts. While he ate he told his mother something of what he had learned.

“So it was all lies,” she observed.

“Not necessarily,” said Crosetti, who was still a little entranced with the fictional version he had concocted. “She

was

obviously on the lam from a bad situation. Parts of it could have been true. She changed the

location and some of the details, but this guy actually locked her in a cellar, according to the kid. She could have been abused as a child and fallen into an abusive situation.”

“But she’s married, which she didn’t bother to mention, and she ran out on her kids. I’m sorry, Allie, but that doesn’t speak well for her. She could have gone to the authorities.”

Crosetti abruptly rose from the table and brought his plate and cup to the sink, and washed them with the clattering movement of the angry. He said, “Yeah, but we weren’t there. Not everybody has a happy family like we do, and the authorities sometimes screw up. We have no idea of what she went through.”

“Okay, Albert,” said Mary Peg, “you don’t have to break the dishes to make a point. You’re right, we don’t know what she went through. I’m just a little worried about your emotional involvement with a married woman you hardly knew. It seems like an obsession.”

Crosetti turned off the faucet and faced his mother. “It

is

an obsession, Mom. I want to find her and I want to help her if I can. And to do that I have to decipher those letters.” He paused. “And I’d like your help.”

“Not a problem, dear,” said his mother, smiling now. “It beats playing Scrabble in the long, long evenings.”

The next day

Mary Peg began rounding up cryptography resources from the Web and through her wide range of contacts in libraries around the world, via telephone and e-mail. Crosetti called Fanny Doubrowicz at the library and was heartened to learn that she had puzzled out Bracegirdle’s Jacobean handwriting and entered the text of his last letter into her computer. She had also made a transcript of the ciphertext of the spy letters and sent a sample of the paper and ink from those originals to the laboratory for analysis. It was, as far as the lab could determine, a seventeenth-century document.

“This Bracegirdle tells quite a story, by the way,” she said. “It will make a revolution in scholarship, unless it is a pack of lies. If only you had not been so foolish as to sell the original!”

“I know, but I can’t do anything about that now,” said Crosetti, expending some effort at keeping his voice pleasant. “If I can find Carolyn I might be able to get it back. Meanwhile, has anything surfaced on the library grapevine? Blockbuster manuscript found?”

“Not even a peep, and I have called around in manuscript circles. If Professor Bulstrode is authenticating it, he is being very quiet about his doings.”

“Isn’t that strange? I figured he’d be calling press conferences.”

“Yes, but this is a man who has been badly burned. He would not want to go public with this until he had made absolutely sure. However, there are only a few people in the world whose word on such a manuscript would be probative, and I have spoken to all of them. They laugh when they hear Bulstrode’s name and none have heard from him recently.”

“Yeah, well, maybe he’s holed up in his secret castle, just gloating. Look, can you zap those documents over by e-mail? I want to get to work on that cipher.”

“Yes, I will zap now. And I will also send the number of my friend, Klim. I think you will need help. I have looked a little and it does not seem to be a simple thing, this cipher.”

When he had the e-mail, Crosetti made himself print out Fannie’s transcription of the Bracegirdle letter instead of reading it immediately on the screen. Then he read it several times, especially the last part, about the spying mission, and tried not to be too hard on himself for letting the original go. He almost sympathized with Bulstrode, the bastard—the discovery was so huge that he could well appreciate what was going through the guy’s mind when he saw it. He did not allow himself to think about the other, larger prize, as Bulstrode had obviously and immediately done, nor did he keep Carolyn and how she was connected to all this uppermost in his thoughts. Crosetti was an indifferent student most days, but he was capable of intense focus when he was interested in something, like the history of movies, a subject on which he was encyclopedic. Now he turned this focus onto the Bracegirdle cipher and on the tall stack of cryptography books his mother had brought home from various libraries that evening.

For the next six days he did nothing else but go to work, study cryptography, and work on the cipher. On Sunday he again went to church and found himself praying with unaccustomed fervor for a solution. Returning home he made for his room, ready to begin once more, when his mother stopped him.

“Take a break, Allie, it’s Sunday.”

“No, I thought of something else I want to try.”

“Honey, you’re exhausted. Your mind is mush and you’re not going to do yourself any good spinning around like a hamster. Sit down, I’ll make a bunch of sandwiches, you’ll have a beer, you’ll tell me what you’ve been doing. This will help, believe me.”

So he forced himself to sit and ate grilled-cheese sandwiches with bacon and drank a Bud, and found that his mother had been right, he did feel a little more human. When the meal was over, Mary Peg asked, “So what have you got so far? Anything?”

“In a negative sense. Do you know much about ciphers?”

“At the Sunday paper game-page level.”

“Yeah, well that’s a start. Okay, the most common kind of secret writing in the early seventeenth century was what they called a nomenclator, which is a kind of enciphered code. You have a short vocabulary of coded words,

box

for

army, pins

for

ships

, whatever, and these words and the connecting words of the message would be enciphered, using a simple substitution, with maybe a few fancy complications. What we got here isn’t a nomenclator. In fact, I think it’s the cipher Bracegirdle talks about in his letter, the one he invented for Lord Dunbarton. It’s not a simple substitution either. I think it’s a true polyalphabetic cipher.”

“Which means what?”

“It’s a little complicated. Let me show you some stuff.” He left and came back with a messy handful of papers. “Okay, the simplest cipher substitutes one letter for another, usually by shifting the alphabet a certain number of spaces, so that A becomes D and C becomes G and so on. It’s called a Caesar shift because Julius Caesar supposedly invented it, but obviously you can crack it in a few minutes if you know the normal frequencies of the letters in the language it’s written in.”

“ETAOIN SHRDLU.”

“You got it. Well, obviously, spies knew this, so they developed ciphering methods to disguise the frequency of letters by using a different alphabet to pick every substitution in the ciphertext.”

“You mean a literally different alphabet, like Greek?”

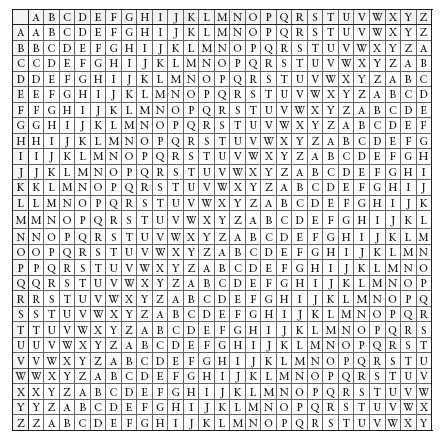

“No, no, I mean like this.” He pulled a paper out of the sheaf and smoothed it on the table. “In the sixteenth century the architect Alberti invented a substitution cipher that used multiple alphabets arranged on brass disks, and a little later in France a mathematician named Blaise Vigenère supposedly invented what they call a polyalphabetic substitution cipher using twenty-six Caesar-shifted alphabets, and I figured it or something like it would be known to Bracegirdle if he was studying the cipher arts at that time. This here is what they call a tabula recta or a Vigenère tableau. It’s twenty-six alphabets, one on top of the other, starting with a regular A through Z alphabet and then each successive one starts one letter to the right, from B through Z plus A, then C through Z plus A and B and so on, and there are regular alphabets along the left side and the top to serve as indexes.”

“So how do you use it to disguise frequencies?”

“You use a key. You pick a particular word and run it across the top of the tableau, lining each letter of the key up with each column and repeating it until you reach the end of the alphabet. For example, let’s pick

Mary Peg

as a key. It’s seven letters with no repeats, so it’s a good pick.” He wrote it out several times in pencil and said, “Now we need a plaintext to encipher.”

“Flee, all is discovered,” suggested Mary Peg.

“Always timely. So we write the plaintext over the key, like so…

F L E E A L L I S D I S C O V E R E D

M A R Y P E G M A R Y P E G M A R Y P

“And then to encipher, we take the first letter of the plaintext, which is F, and the first letter of the key, which is M, and then we go to the tableau, down from the F column to the row and we write the letter

we find at the intersection, which just happens to be R. The next combination is L from

flee

and A from

Mary

, so L stays L, and the next is E and R, which gives V. And now see how this works: the next E is over the letter Y in our ‘Mary Peg’ key which gives C. The two Es in

flee

have

different

ciphertext equivalents, which is why frequency analysis fails. Let me knock this out real quick so you can see….”

Crosetti rapidly filled in the ciphertext and produced

F L E E A L L I S D I S C O V E R E D

R L V C P P R U S U G H G U H E I C S

“And notice how the double L in

all

is disguised too,” he said. “Now you have something that can’t be broken by simple frequency analysis, and for three hundred years no one could break a cipher like that without learning the key word. That’s mainly what they tortured spies for.”

“How

do

you break it?”

“By finding the length of the key word, and you do that by analyzing repeating patterns in the ciphertext. It’s called the Kasiski-Kerckhoff Method. In a long enough message or set of messages,

FL

is going to line up with

MA

again, and give you

RL

again, and there’ll be other two-and three-letter patterns, and then you count the distance between repeats and figure out any common numerical factors. In our example, with a seven-letter key you might get repeats at seven, fourteen, and twenty-one significantly more than would be the case by chance. Obviously, nowadays you use statistical tools and computers. Then when you know our key has seven letters, it’s a piece of cake, because what you have then is seven simple substitution alphabets derived from the Vigenère tableau, and you can break those by ordinary frequency analysis to decrypt the ciphertext or reconstruct the key word. There are downloadable decrypting programs that can do it in seconds on a PC.”

“So why haven’t you cracked it?”

He ran his hand through his hair and groaned. “If I knew that, I’d

know

how to crack it. This thing’s not a simple Vigenère.”

“Maybe it is, but it has a really long key. From what you said, the longer the key, the harder it would be to factor out the repeating groups.”

“Good point. The problem with long keys is that they’re easy to forget and hard to transmit if you want to change them. For instance, if these guys wanted to change the key every month to make absolutely sure that no spy had discovered it, they’d want something an agent could receive with a whisper in the dark or in a totally innocent message. What they do nowadays is that the agent gets what they call a onetime pad, which is a set of preprinted segments of an infinitely long, totally random key. The agent enciphers one message and then burns the sheet. It’s

totally unbreakable even by advanced computers. But that kind of method wasn’t invented in 1610.”