The Book of Animal Ignorance (34 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

F

ifty-five million years ago, small hoofed carnivores started to move from the land back into the sea. Those wonderful pictures of legs becoming fins and tails, bodies becoming longer and more streamlined, nostrils moving back and up, seem to run the evolutionary clock backwards. DNA evidence now shows us that whales have nothing to do with other water-based meat-eaters like seals and walruses; their closest living relative is the vegetarian hippo, with deer, camels and pigs as very distant cousins. It's one of evolution's most compelling stories: how a clumsy, crocodile-shaped otter ends up producing the largest, most graceful and mysterious of all the creatures on the planet.

Blue whales were

only caught after

the invention of the

âgrenade' harpoon

in 1868. In 1931,

29,000 were killed

in one season.

There are now

fewer than 5,000 â

one whale for every

8,500 cubic miles of

their ocean habitat

.

The blue whale is the largest animal that has ever lived by a huge margin: thirty times heavier than an African elephant, the next largest mammal. The biggest dinosaur weighed less than half as much: some female blue whales can lose as much as 50 tons when feeding their young. A newborn blue whale is the same weight as a female elephant: it puts on 14 stone a day, 8 lb an hour. When fully grown, its heart is the same size as a family car, processing 2,000 gallons of blood, pumping 60 gallons a beat, with an aorta large enough for a five-year-old child to swim through.

Whales grew large because the buoyancy of water meant they could â nothing so heavy could survive on land; the energy needed to move and feed would be too great. But for a warmblooded animal living in the sea is problematic: it's a desert â there's nothing to drink. And it's cold: heat travels twenty-four times faster in water. Being large helps, as it reduces the surface-

to-weight ratio, but the real star of whale survival is blubber. It not only acts as an insulating overcoat and life-jacket (it's less dense than seawater); it also stores the water extracted from food and provides a handy on-board supply of nutrients when food is scarce.

WHY THE BIG

NOSE?

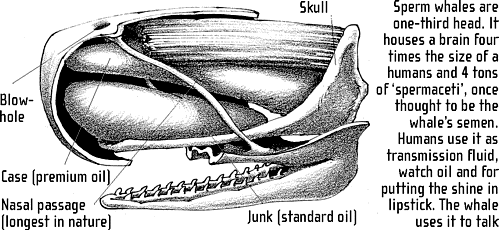

Communicating in water is also a challenge. Smell is useless, sight limited and touch is tricky when you have fins rather than fingers. But sound waves travel four times faster under water, and whales have turned the ocean itself into a sophisticated communication system. Whale song is the loudest noise made by any single animal: some songs are so low in frequency that they can be felt thousands of miles away. The massive head of the sperm whale focuses sound into a burst that can stun a giant squid but it also acts as a kind of acoustic retina, a giant IMAX sound screen through which it interprets its dark world. The half-hour songs of the humpback whale contain grammatical rules: sounds are combined into structures that operate like syntax, packing the song with millions of discrete units of information. Whales sing in different dialects depending on where they're from, and sing different songs in different places at different times of the year.

Whether these songs are sat-nav read-outs, shipping forecasts, personal ads or epic poetry, we will never know. What we do know is that military sonar and general noise pollution in the sea has reduced their carrying range by 80 per cent and many stranded whales have severe inner ear damage. We may not hunt whales as once we did, but we still torment them.

W

oodlice are land-based crustaceans, and, despite appearances, are much more closely related to shrimps and lobsters than they are to millipedes or centipedes.

They have blue blood and still breathe using gills, These are attached to the pairs of

pleopods

(literally, âswimming feet') on their abdomen and contain a branching network of moist tubes that allow them to extract oxygen from air, although a woodlouse will survive quite happily in water for up to an hour.

Woodlice have a rich array of nicknames: âsow bugs', âball bugs', âarmadillo bugs', âslaters', âgrammerzows', âchiggy pigs', âcheeselogs' âbibble bugs', âcud worms', âcoffin cutters', âmonkey peas', âpea bugs', âgranny-ants', âgranfers', âBilly Bakers' and âtiggyhogs'. In Holland they are called

pissebed

(literally âpiss-in-the-bed'). This is because they don't urinate: their porous shell also allows them to expel their waste as ammonia vapour rather than liquid urine. They produce more nitrogenous waste for their size than any other animal.

The porous shell also means they are vulnerable to dehydration. Their tendency to clump together in large groups helps keep them moist and protects them from predators. Toads, shrews and centipedes are all keen on woodlice. Blowfly larvae also burrow into woodlice and eat them from the inside. The woodlouse spider (

Dysdera crocata

) lives on nothing else and has specially adapted fangs for piercing their shells.

Woodlice were eaten as a

cure for stomach upsets,

rather like Rennies â their

shell is made from calcium

carbonate, which neutralises

the acid in the stomach

.

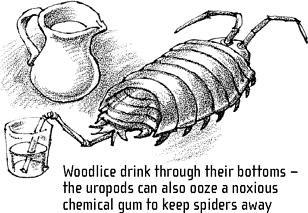

Woodlice do use their bottoms to drink. Small forked tubes called

uropods suck water into their anuses. They're not fussy eaters either. They prefer rotting vegetation, but in lean months their own faeces will do. There's a New Zealand species, the sea slater (

Scyphax ornatus

), that survives mostly on drowned honeybees. Their odd personal habits make them good news in a compost heap and their fondness for munching through rubbish has led to them being employed by natural history museums to clean delicate animal skeletons.

Woodlice are members of the Isopod order (meaning âequal feet'). There are 3,500 species and they've been around for 160 million years. They carry their young in pouches, moult regularly and live for about two years. Not all of them clump together in damp crevices. The desert woodlouse (

Hemilepistus reaumuri

) pairs for life, navigates by the sun and lives in organised colonies of burrows where the young do the housework. They can walk several miles a day.

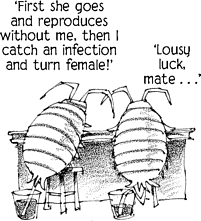

It's tough being a male woodlouse. Not only can females give birth without mating (parthenogenesis), but males infected with a certain bacterium actually turn into females.

The Deep sea isopod (

Bathynomus giganteus

) is a giant aquatic woodlouse that lives on the icy darkness of the ocean floor and hoovers up dead whales. They are white, 2 feet long and weigh as much as a decent-sized lobster.

Woodlice are perfectly edible. In his polemical pamphlet

Why Not

Eat Insects?

(1885), Vincent M. Holt considered their flavour superior to shrimp and gave a recipe for a woodlouse sauce for fish.

T

he woodpecker's tongue is one of the most amazing of all animal organs, so much so that it often gets cited by creationists as âproof' that evolution is flawed. In some species it can extend to fully two-thirds of the bird's body length, is covered in sticky saliva, has vicious barbs and has an âear' at the end of it. In fact, tongue structure of the woodpecker is very similar to that of most other birds: it's just longer, presumably because this delivered the evolutionary advantage of being able to reach deeper into the tree for insects. The secret is a series of wafer-thin hyoid bones, that fold up like an accordion in a fluid-filled sheath when the tongue is not being used. As the woodpecker sticks out its tongue, powerful muscles contract near the base, forcing the bones forward and the tongue out of the bill. Relaxing the muscles brings it back inside. When a woodpecker is born, its tongue is anchored near its ears, much like a chicken's. As it grows, the hyoid sheath gradually extends around and over the skull, when it fuses with the back of the nostrils. As for the ear on the tongue's tip, this is a concentration of pressure-sensitive nerve endings called Herbst's corpuscles that feel the tiniest vibrations of insect prey.

My father told me

all about the

birds and the

bees, the liar. I

went steady with

a woodpecker till

I was twenty-one

.

BOB HOPE

There are over 200 species of woodpecker, and each has a particular speed and rhythm of drilling, some reaching sixteen blows per second. Every time a wood-pecker brings its head to a halt, the force is equivalent to a thousand times the force of gravity (or 250 times the force an astronaut is subjected to during lift-off). The reason that their heads do not shatter is a sponge-like cartilage cushion that absorbs most of the shock. Also, every time the woodpecker strikes a blow, a muscle pulls the brain-case away from the beak.

Woodpecker drumming isn't searching for food. It's a species âsignature' used to communicate and attract mates. Woodpeckers often choose materials where the resonance is high â dead trees, metal drainpipes or wooden eaves. They drum at different rates when insect-hunting or excavating nests. In 1995, a pair of Northern Flickers (

Colaptes auratus

) drilled 200 holes into the foam insulation of the shuttle

Discovery

's external tank, delaying its launch.

Green woodpeckers (

Picus viridis

) are also known as rainbirds â hearing their distinctive âlaughing' call means rain is on its way. This dates back to an early version of the Genesis story, where the woodpecker refused to help God excavate the rivers and oceans and was punished by being forced to peck wood and drink rain. The bird once had forty English vernacular names including Hewhole, Wudewale and Galley Bird, but the one still used is âYaffle'. Most people assume this refers to its laugh but it actually means âto eat greedily'. Which green woodpeckers do, as anyone who's ever seen one attacking an anthill will testify. They can get through 2,000 ants in a single sitting.