The Book of Fate (26 page)

The Roman banked into a nearby parking spot, shut his briefcase, and pulled the earpiece from his ear. Wes was smarter than they’d bargained for. He wouldn’t be hearing Wes’s voice anytime soon. But that was why he made the trip in the first place. Having patience was fine for catching fish. But the way things were going, some problems required an approach that was more hands-on.

From the bottom of the briefcase, The Roman pulled his 9mm SIG revolver, cocked it once, then slid it into the leather holster inside his black suit jacket. Slamming his car door with a thunderclap, he marched straight for the front entrance of the building.

“Sir, I’ll need to see some ID,” an officer in a sheriff’s uniform called out with a hint of North Florida twang.

The Roman stopped, arcing his head sideways. Touching the tip of his tongue to the dip in his top lip, he reached into his jacket . . .

“Hands where I can—!”

“Easy there,” The Roman replied as he pulled out a black eelskin wallet. “We’re all on the same side.” Flipping open the wallet, he revealed a photo ID and a gold badge with a familiar five-pronged star. “Deputy Assistant Director Egen,” The Roman said. “Secret Service.”

“Damn, man, why didn’t you just say so?” the sheriff asked with a laugh as he refastened the strap for his gun. “I almost put a few in ya.”

“No need for that,” The Roman said, studying his own wavy reflection as he approached the front glass doors. “Especially on such a beautiful day.”

Inside, he approached the sign-in desk and eyed the sculpted bronze bust in the corner of the lobby. He didn’t need to read the engraved plaque below it to identify the rest.

Welcome to the offices of Leland F. Manning. Former President of the United States.

T

he Roman’s a hero,” Lisbeth begins, reading from the narrow reporter’s pad that she pulls out of her folder. “Or a self-serving narc, depending on your political affiliation.”

“Republican vs. Democrat?” Dreidel asks.

“Worse,” Lisbeth clarifies. “Reasonable people vs. ruthless lunatics.”

“I don’t understand,” I tell her.

“The Roman’s a C.I.—confidential informant. Last year, the CIA paid him $70,000 for a tip about the whereabouts of two Iranian men trying to build a chemical bomb in Weybridge, just outside of London. Two years ago, they paid him $120,000 to help them track an al-Zarqawi group supposedly smuggling VX gas through Syria. But the real heyday was almost a decade ago, when they paid him regularly—$150,000 a pop—for tips about nearly every terrorist activity hatching inside Sudan. Those were his specialties. Arms sales . . . terrorist whereabouts . . . weapons collection. He knew what the real U.S. currency was.”

“I’m not sure I follow,” Rogo says.

“Money, soldiers, weapons . . . all the old measuring sticks for winning a war are gone,” Lisbeth adds. “In today’s world, the most important thing the military needs—and rarely has—is good, solid, reliable intel. Information is king. And it’s the one thing The Roman somehow always had the inside track on.”

“Says

who

?” Dreidel asks skeptically. After all his time in the Oval, he knows that a story’s only as good as the research behind it.

“One of our old reporters who used to cover the CIA for the

L.A. Times

,” Lisbeth shoots back. “Or is that not a prestigious enough paper for you?”

“Wait, so The Roman’s on

our

side?” I ask.

Lisbeth shakes her head. “Informants don’t take sides—they just dance for the highest bidder.”

“So he’s a good informant?” I ask.

“

Good

would be the guy who ratted out those Asian terrorists who were targeting Philadelphia a few years back. The Roman’s great.”

“How great?” Rogo asks.

Lisbeth flips to a new sheet of her notepad. “Great enough to ask for a six-million-dollar payout for a single tip. Though apparently, he didn’t get it. CIA eventually said no.”

“That’s a lot of money,” Rogo says, leaning in and reading off her notepad.

“And that’s the point,” Lisbeth agrees. “The average payout for an informant is small: $10,000 or so. Maybe they’ll give you $25,000 to $50,000 if you’re really helpful . . . then up to $500,000 if you’re giving them specific info about an actual terrorist cell. But six million? Let’s put it this way: You better be close enough to know bin Laden’s taste in toothpaste. So for The Roman to even demand that kind of cash . . .”

“He must’ve been sitting on an elephant-sized secret,” I say, completing the thought.

“Maybe he tipped them about Boyle being shot,” Rogo adds.

“Or whatever it was that led up to it,” Lisbeth says. “Apparently, the request was about a year before the shooting.”

“But you said the CIA didn’t pay it,” Dreidel counters.

“They wanted to. But they apparently couldn’t clear it with the higher-ups,” Lisbeth explains.

“Higher-ups?” I ask. “How higher up?”

Dreidel knows where I’m going. “What, you think Manning denied The Roman’s pot of gold?”

“I have no idea,” I tell him.

“But it makes sense,” Rogo interrupts. “’Cause if someone got in the way of

me

getting a six-million-dollar payday, I’d be grabbing my daddy’s shotgun to take a few potshots.”

Lisbeth stares him down. “You go to those action movies on opening night, don’t you?”

“Can we please stay on track?” I beg, then ask her, “Did your reporter friend say anything else about what the six-million-dollar tip was about?”

“No one knows. He was actually more fascinated with how The Roman kept pulling rabbits out of his hat year after year. Apparently, he’d just appear out of nowhere, drop a bombshell about a terrorist cell in Sudan or a group of captured hostages, then disappear until the next emergency.”

“Like Superman,” Rogo says.

“Yeah, except Superman doesn’t charge you a few hundred grand before he saves your life. Make no mistake, The Roman’s heartless. If the CIA didn’t meet his price, he was just as happy to walk away and let a hostage get his head sawed off. That’s why he got the big cash. He didn’t care. And apparently still doesn’t.”

“Is he still based in Sudan?” I ask.

“No one knows. Some say he might be in the States. Others wonder if he’s getting fed directly from inside.”

“Y’mean like he’s got someone in the CIA?” Rogo asks.

“Or FBI. Or NSA. Or even the Service. They all gather intelligence.”

“It happens all the time,” Dreidel agrees. “Some midlevel agent gets tired of his midlevel salary and one day decides that instead of typing up a report about Criminal X, he’ll pass it along to a so-called informant, who then sells it right back and splits the reward with him.”

“Or he makes up a fake identity—maybe calls himself something ridiculous like

The Roman

—and then just sells it back to himself. Now he’s getting a huge payday for what he’d otherwise do in the course of his job,” I say.

“Either way, The Roman’s supposedly dug in so deep, his handlers had to design this whole ridiculous communication system just to get in touch with him. Y’know, like reading every fifth letter in some classified ad . . .”

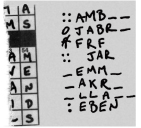

“Or mixing up the letters in a crossword,” Dreidel mutters, suddenly sitting up straight. Turning to me, he adds, “Let me see the puzzle . . .”

From my pants pocket, I pull out the fax of the crossword and flatten it with my palm on the conference table. Dreidel and I lean in from one side. Rogo and Lisbeth lean in from the other. Although they both heard the story last night, this is the first time Rogo and Lisbeth have seen it.

Studying the puzzle, they focus on the filled-in boxes, but don’t see anything beyond a bunch of crossword answers and some random doodling in the margins.

“What about those names on the other sheet?” Lisbeth asks, pulling out the page below the crossword and revealing the first page of the fax, with the

Beetle Bailey

and

Blondie

comic strips. Just above Beetle Bailey’s head, in the President’s handwriting, are the words

Gov. Roche . . . M. Heatson . . . Host—Mary Angel.

“I looked those up last night,” I say. “The puzzle’s dated February 25, right at the beginning of the administration. That night, Governor Tom Roche introduced the President at a literacy event in New York. In his opening remarks, Manning thanked the main organizer, Michael Heatson, and his host for the event, a woman named Mary Angel.”

“So those names were just a crib sheet?” Lisbeth asks.

“He does it all the time,” Dreidel says.

“

All

the time,” I agree. “I’ll hand him a speech, and as he’s up on the dais, he’ll jot some quick notes to himself adding a few more people to thank—some big donor he sees in the front row . . . an old friend whose name he just remembered . . . This one just happens to be on the back of a crossword.”

“I’m just amazed they save his old puzzles,” Lisbeth says.

“That’s the thing. They don’t,” I tell her. “And believe me, we used to save

everything

: scribbled notes on a Post-it . . . an added line for a speech that he jotted on a cocktail napkin. All of that’s work product. Crosswords aren’t, which is why they’re one of the few things we were allowed to throw away.”

“So why’d this one get saved?” Lisbeth asks.

“Because

this

is part of a speech,” Dreidel replies, slapping his hand against Beetle Bailey’s face.

Gov. Roche . . . M. Heatson . . . Host—Mary Angel.

“Once he wrote those, it was like locking the whole damn document in amber. We had to save it.”

“So for eight years, Boyle’s out there, requesting thousands of documents, looking for whatever he’s looking for,” Lisbeth says. “And one week ago, he got these pages and suddenly comes out of hiding.” She sits up straight, sliding her leg under her rear end. I can hear the speed in her voice. She knows it’s in here.

“Lemme see the puzzle again,” she says.

Like before, all four of us crowd around it, picking it apart.

“Who’s the other handwriting besides Manning’s?” Lisbeth asks, pointing to the meticulous, squat scribbles.

“Albright’s, our old chief of staff,” Dreidel answers.

“He died a few years ago, right?”

“Yeah—though so did Boyle,” I say, leaning forward so hard, the conference table digs into my stomach.

Lisbeth’s still scanning the puzzle. “From what I can tell, all the answers seem right.”

“What about this stuff over here?” Rogo asks, tapping at the doodles and random lettering on the right side of the puzzle.

“The first word’s

amble

. . . see 7 across?” I ask. “The spaces are for the

L

and the

E.

Dreidel said his mom does the same thing when she does puzzles.”

“Sorta scribbles out different permutations to see what fits,” Dreidel explains.

“My dad used to do the same,” Lisbeth agrees.

Rogo nods to himself but won’t take his eyes off it.

“Maybe the answer’s in the crossword clues,” Lisbeth suggests.

“What, like The Roman had an in with the puzzlemaker?” Dreidel asks, shaking his head.

“And that’s more insane than it being hidden in the answers?”

“What was the name of that guy from the White House with the chipmunk cheeks?” Rogo interrupts, his eyes still on the puzzle.

“Rosenman,” Dreidel and I say simultaneously.

“And your old national security guy?” Rogo asks.

“Carl Moss,” Dreidel and I say again in perfect sync.

I stay with Rogo. Whenever he’s this quiet, the pot’s about to boil. “You see something?” I ask.

Looking up slightly, Rogo smiles his wide butcher’s dog smile.

“What? Say it already,” Dreidel demands.

Rogo grips the edge of the crossword and flicks it like a Frisbee across the table. “From the looks of it, the names of all your staffers are hidden right there.”

I

n the lobby, The Roman didn’t hesitate to sign in. Even made small talk about crummy assignments with the agent behind the desk. At the elevators, he rang the call button without worrying about his fingerprints. Same when the elevator doors opened and he hit the button for the fourth floor.

It was exactly why they got organized. The key to any war was information. And as they learned with the crossword puzzle all those years ago, the best information always came from having someone on the inside.

A loud ping flicked the air as the elevator doors slid open.

“ID, please,” a suit-and-tie agent announced before The Roman could even step out into the beige-carpeted hallway.

“Egen,” The Roman replied, once again flashing his ID and badge.

“Yes . . . of course . . . sorry, sir,” the agent said, stepping back as he read the title on The Roman’s ID.

With a wave, The Roman motioned for him to calm down.

“So if you don’t mind me asking, what’s the mood at headquarters?” the agent asked.

“Take a guess.”

“Director’s pretty pissed, huh?”

“He’s just mad he’ll be spending the next six months on the damage control circuit. Ain’t nothing worse than a daily diet of cable talk shows and congressional hearings explaining why Nico Hadrian wandered out of his hospital room.”