The Book of Fate (49 page)

“Everything okay?”

“I-I don’t think so.”

Hearing the pain in Wes’s voice, Lisbeth turned back to Kassal.

“Go,” the old man told her, readjusting his bifocals. “I’ll call you as soon as I find something.”

“Are you—?”

“Go,” he insisted, trying to sound annoyed. “Young redheads are just a distraction anyway.”

Nodding a thank-you and scribbling her number on a Post-it for him, Lisbeth ran for the door. Turning back to her cell, she asked Wes, “How can I help?”

On the other end, Wes finally exhaled. Lisbeth couldn’t tell if it was relief or excitement.

“That depends,” he replied. “How fast can you get to Woodlawn?”

“Woodlawn Cemetery? Why there?”

“That’s where Boyle asked to meet. Seven p.m. At his grave.”

F

ighting traffic for nearly an hour, Rogo veered to the right, zipping off the highway at the exit for Griffin Road in Fort Lauderdale.

“Y’know, for a guy who deals with traffic tickets every single day,” Dreidel said, gripping the inside door handle for support, “you think you’d appreciate safe driving a bit more.”

“If I get a ticket, I’ll get us off,” Rogo said coldly, jabbing the gas and going even faster down the dark off-ramp. Wes had enough of a head start. Priority now was finding why Boyle was seeing Dr. Eng—in Florida—the week before the shooting.

“There’s no way he’ll even be there,” Dreidel said, looking down at his watch. “I mean, name one doctor who works past five o’clock,” he added with a nervous laugh.

“Stop talking, okay? We’re almost there.”

With a sharp left that took them under the overpass of I-95, the blue Toyota headed west on Griffin, past a string of check-cashing stores, two thrift shops, and an adult video store called AAA to XXX.

“Great neighborhood,” Rogo pointed out as they passed the bright neon purple and green sign for the Fantasy Lounge.

“It’s not that ba—”

Directly above them, a thunderous rumble ripped through the sky as a red and white 747 whizzed overhead, coming in for a landing at Fort Lauderdale Airport, which, judging from the height of the plane, was barely a mile behind them.

“Maybe Dr. Eng just likes cheap rents,” Dreidel said as Rogo reread the address from the entry in Boyle’s old calendar.

“If we’re lucky, you’ll be able to ask him personally,” Rogo said, pointing out the front windshield. Directly ahead, just past a funeral home, bright lights lit up a narrow office park and its modern four-story white building with frosted-glass doors and windows. Along the upper half of the building, a thin yellow horizontal stripe ran just below the roofline.

2678 Griffin Road.

D

uring the first year, Ron Boyle was scared. Shuttling from country to country . . . the nose contouring and cheek implants . . . even the accent modification that never really worked. The men in Dr. Eng’s office said it’d keep him safe, make his trail impossible to follow. But that didn’t stop him from bolting upright in his bed every time he heard a car door slam outside his motel or villa or pensione. The worst was when a spray of firecrackers exploded outside a nearby cathedral—a wedding tradition in Valencia, Spain. Naturally, Boyle knew it wouldn’t be easy—hiding away, leaving friends, family . . . especially family—but he knew what was at stake. And in the end, when he finally came back, it’d all be worth it. From there, the rationalizations were easy. Unlike his father, he was tackling his problems head-on. And as he closed his eyes at night, he knew no one could blame him for that.

By year two, as he adjusted to life in Spain, isolation hit far harder than his accountant brain had calculated. Unlike his old friend Manning, when Boyle left the White House, he never suffered from spotlight starvation. But the loneliness . . . not so much for his wife (his marriage was finished years ago), but on his daughter’s sixteenth birthday, as he pictured her gushing, no-more-braces smile in her brand-new driver’s license photo—those were the days of regret. Days that Leland Manning would answer for.

In year three, he’d grown accustomed to all the tricks Dr. Eng’s office taught him: walking down the street with his head down, double-checking doors after he entered a building, even being careful not to leave big tips so he wouldn’t be remembered by waiters or staff. So accustomed, in fact, that he made his first mistake: making small talk with a local ex-pat as they both sipped

horchatas

in a local bodega. Boyle knew the instant the man took a double take that he was an Agency man. Panicking, but smart enough to stay and finish the drink, Boyle went straight home, frantically packed two suitcases, and left Valencia that evening.

In December of that same year, the

New Yorker

commissioned a feature article about Univar “Blackbird” computers showing up in the governments of Iran, Syria, Burma, and Sudan. As terrorist nations unable to import from the United States, the countries bought their computers from a shady supplier in the Middle East. But what the countries didn’t know was that Univar was a front company for the National Security Agency and that six months after the computers were in the terrorist countries’ possession, they slowly broke down while simultaneously forwarding their entire hard drives straight to the NSA—hence the

Blackbird

codename—as the info flew the coop.

But as the research for the

New Yorker

article pointed out, during the Manning administration, one Blackbird computer from Sudan didn’t forward its hard drive to the NSA. And when the others did, the remaining Blackbird was removed from the country, eventually making its way to the black market. The informant who held it wanted a six-million-dollar ransom from the United States for its return. But Manning’s staff, worried it was a scam, refused to pay. Two weeks before the

New Yorker

story was to be handed in, Patrick Gould, the author of the article, died from a sudden ruptured brain aneurysm. The autopsy ruled out foul play.

By year four, Boyle was well hidden in a small town outside London, in a flat tucked just above a local wedding cake bakery. And while the smell of fresh hazelnut and vanilla greeted him every morning, frustration and regret slowly buried Boyle’s fear. It was only compounded when the Manning Presidential Library was two months behind its scheduled opening, making his search for papers, documents, and proof that much harder to come by. Still, that didn’t mean there was nothing for him to dig through. Books, magazines, and newspaper profiles had been written about Nico, and the end of Manning’s presidency, and the attack. With each one, as Boyle relived the sixty-three seconds of the speedway shooting, the fear returned, churning through his chest and the scarred palm of his hand. Not just because of the ferocity of the attack, or even the almost military efficiency of it, but because of the gall: at the speedway, on live television, in front of millions of people. If The Three wanted Boyle dead, they could’ve waited outside his Virginia home and slit his throat or forced a “brain aneurysm.” To take him down at the speedway, to do it in front of all those witnesses . . . risks that big were only worth taking if there was some kind of added benefit.

Year four was also when Boyle started writing his letters. To his daughter. His friends. Even to his old enemies, including the few who missed his funeral. Asking questions, telling stories, anything to feel that connection to his real life, his former life. He got the idea from a biography of President Harry Truman, who used to write scathing letters to his detractors. Like Truman, Boyle wrote hundreds of them. Like Truman, he didn’t mail them.

In year five, Boyle’s wife remarried. His daughter started college at Columbia on a scholarship named after her dead father. Neither broke Boyle’s heart. But they certainly jabbed a spike in his spirit. Soon after, as he’d been doing since year one, Boyle found himself in an Internet café, checking airfares back to the States. A few times, he’d even made a reservation. He’d long ago worked out how he’d get in touch, how he’d contact his daughter, how he’d sneak away—even from those he knew were always watching. That’s when the consequences would slap him awake. The Three . . . The Four . . . whatever they called themselves, had already—Boyle couldn’t even think about it. He wasn’t risking it again. Instead, as the Manning Presidential Library threw its doors open, Boyle threw himself into the paperwork of his own past, mailing off his requests and searching and scavenging for anything to prove what his gut had been telling him for years.

By year six, he was ankle-deep in photocopies and old White House files. Dr. Eng’s people offered to help, but Boyle was six years past naive. In the world of Eng, the only priority was Eng, which was why, when Manning had him introduced to Dr. Eng’s group all those years ago, Boyle told them about The Three, and their offer to make him The Fourth, and the threats that went along with it. But what he never mentioned—not to anyone—was what The Three had already stolen. And what Boyle was determined to get back.

He’d finally gotten his chance eleven days ago, on a muddy, rainy afternoon in the final month of year seven. Huddled under the awning as he stepped out of the post office on Balham High Road, Boyle flipped through the newly processed releases from Manning’s personal handwriting file. Among the highlights were a note to the governor of Kentucky, some handwritten notes for a speech in Ohio, and a torn scrap from the

Washington Post

comics section that had a few scribbled names on one side . . . and a mostly completed crossword puzzle on the other.

At first, Boyle almost tossed it aside. Then he remembered that day at the racetrack, in the back of the limo, Manning and his chief of staff were working a crossword. In fact, now that he thought about it, they were

always

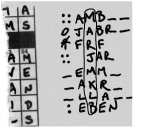

working a crossword. Staring down at the puzzle, Boyle felt like there were thin metal straps constricting his rib cage. His teeth picked at his bottom lip as he studied the two distinct handwritings. Manning’s and Albright’s. But when he saw the random doodles along the side of the puzzle, he held his breath, almost biting through his own skin. In the work space . . . the initials . . . were those—? Boyle checked and rechecked again, circling them with a pen.

Those weren’t just senior staff. With Dreidel and Moss and Kutz—those were the people getting the President’s Daily Briefing, the one document The Three asked him for access to.

It took three days to crack the rest: two with a symbols expert at Oxford University, half a day with an art history professor, then a fifteen-minute consultation with their Modern History Research Unit, most specifically, Professor Jacqui Moriceau, whose specialty was the Federalist period, specifically Thomas Jefferson.

She recognized it instantly. The four dots . . . the slashed cross . . . even the short horizontal dashes. There they were. Exactly as Thomas Jefferson had intended.

As Professor Moriceau relayed the rest, Boyle waited for his eyes to flood, for his chin to rise with the relief of a seemingly lifelong mission complete. But as he held the crossword in his open palm . . . as he slowly realized what Leland Manning was really up to . . . his arms, his legs, his fingertips, even his toes went brittle and numb, as if his whole body were a hollowed-out eggshell. God, how could he be so blind—so trusting—for so long? Now he had to see Manning. Had to ask him to his face. Sure, he’d unlocked the puzzle, but it wasn’t a victory. After eight years, dozens of missed birthdays, seven missed Christmases, six countries, two surgeries, a prom, a high school graduation, and a college acceptance, there would never be victory.

But that didn’t mean there couldn’t be revenge.

Fifteen minutes south of Palm Beach, Ron Boyle pulled to the side of the highway and steered the beat-up white van to the far corner of a dead-empty emergency rest stop. Without even thinking about it, he angled just behind a crush of ratty, overgrown shrubs. After eight years, he had a PhD in disappearing.

Behind him, sprawled along the van’s unlined metal floor, O’Shea shuddered and moaned, finally waking up. Boyle wasn’t worried. Or scared. Or even excited. In fact, it’d been weeks since he felt much of anything beyond the ache of his own regrets.

On the floor, with his arms still tied behind his back, O’Shea scootched on his knees, his chin, his elbows, slowly and sluggishly fighting to sit up. With each movement, his shoulder twitched and jumped. His hair was a sopping mess of rain and sweat. His once-white shirt was damp with dark red blood. Eventually writhing his way to a kneeling position, he was trying to look strong, but Boyle could see in the grayish coloring of his face that the pain was taking its toll. O’Shea blinked twice to get his bearings.

That’s when O’Shea heard the metallic click.

Crouching in the back of the van, Boyle leaned forward, pressed his pistol deep into O’Shea’s temple, and said the words that had been haunting him for the better part of a decade:

“Where the fuck’s my son?”

C

an I help you?” a deep voice crackled from the intercom as the man pulled his car up to the closed wooden security gate.