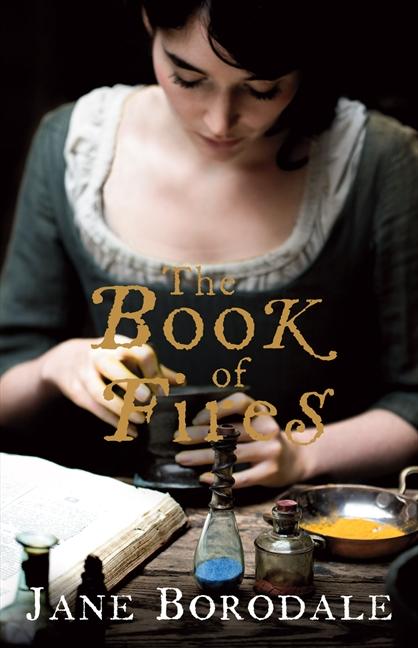

The Book of Fires

Authors: Jane Borodale

Table of Contents

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2 , Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632 ,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2 , Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632 ,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

A Pamela Dorman Book / Viking

Publisher’s Note

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business

establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business

establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Borodale, Jane.

The book of fires : a novel / Jane Borodale.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

The book of fires : a novel / Jane Borodale.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN : 978-1-101-18986-3

1. Women—Fiction. 2. London (England)—History—18thcentury—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6102.O76B66 2010

823’.92—dc22 2009027163

PR6102.O76B66 2010

823’.92—dc22 2009027163

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Sean, Orlando and Louis

With thoughts spared

for all those condemned to death by hanging at Tyburn

for all those condemned to death by hanging at Tyburn

Fixed Suns

1

T

here is a regular rasp of a blade on a stone as he sharpens the knives. The blade makes a shuddery, tight noise that I feel in my teeth. It’s November, and today is the day that we kill the pig.

here is a regular rasp of a blade on a stone as he sharpens the knives. The blade makes a shuddery, tight noise that I feel in my teeth. It’s November, and today is the day that we kill the pig.

I am inside the house, bending over the hearth. I lay pieces of dry elm and bark over the embers and they begin to kindle as the fire takes. A warm fungus smell rises up and the logs bubble juices and resin. The fed flames spit and crackle, colored jets hissing out wet. A column of thick smoke pours rapidly up the chimney and out into the sky like a gray liquid into milk. I hang the bellows from the strap and straighten up. Fire makes me feel good. Burning things into ash and nothingness makes my purpose seem clearer.

When I stand back, I see that the kitchen is full of smoke. My mother is busy and short of breath, flustering between the trestles and the fire-side, two blotches of color rising on her cheekbones. This fire must be a roasting blaze, one of the hottest of the year. It has to heat the biggest pots brimful with boiling water to scald the pigskin, and later will simmer the barley and puddings, fatty blood and grain packed into the washed guts, moving cleanly around in the cauldron of water. I go to the door and step out into the yard to fetch more wood. The weather is not gasping cold yet, but the chill is here. It is already not far till Martinmas, though the frosts have not set in like most years, and my breath is a white cloud ahead of me. A low sun has risen over the valley, pushing thin shadows into the lane. The damp air smells of rotting leaves and dung and the smoke from the chimney. I can hear rooks making coarse-throated noises over the beech trees on the hill. And my brother Ab is whetting the blades by the back door, scraping the metal over the stone away from him. As I cross the yard to the wood stack, I see the knife catching the shine of the orange sun as he works, a sharp flash of blinding light.

I whisper a list of things into the wood stack as I pull out logs and branches and pile them up against the front of my dress.

My name is Agnes

.

.

I live in a cottage on the edge of the village of Washington, at the foot of the Downs where the greensand turns into clay. The lane that leads past the cottage is narrow and muddy, and floods with a milky whiteness when the rain pours down from the hill. Above us the scarp is thickly wooded, up to the open chalk tops where the sheep graze. My father’s family has been in Sussex for years. I am seventeen, we are quite often hungry, I work half of the day weaving cloth for the trade. And for the remainder, I do what girls do: stir the pots, feed the hens, slap the wind from the babies, make soap, make threepence go further . . .

His knife has paused. There is an unsteadiness on the air, something that does not add up to what I say. I stop myself talking and balance the armful of logs up on my shoulder to carry in.

The earth floor of the kitchen is a clutter of borrowed pots. We collected them from Mrs. Mellin days ago and are scalding them clean. My mother is counting out onions and shallots ready for chopping. She reaches up to the salt box over the mantel.

“Mother! Hester’s grizzling,” I say to her loudly over the confusion of children, as though she were deaf, and she leaves the hearth and ducks into the back room, bending her long uncomfortable body over the truckle bed to pick up Hester. Her back is like a twist inside her clothes as she jigs the baby up and down on her hip to make her quiet. Her patience wears a little thinner with each child that comes.

We have debts in the village. My father’s work pays less since enclosure started, and he has been looking for any hiring that he can get. There is no more hedging work in the district. Last week he came home with six blue rock doves that we hid in a pile in the brewhouse until he could take them to Pulborough for the fair. My mother had been angry all day and when he came back after dark they fought for hours, using up rushlight. When we came down from the chamber in the morning I saw one of the jugs was cracked but put away tidily at the back of the shelf. This is the third full year we have not had a strip to grow a crop, and even the common land could be gone by the next, so this is the last pig.

Through the door into the back room my father’s feet are just visible at the end of the other bed under the blanket. He will be up soon, before my uncle arrives.

“We are doing the pig early this year, but we owe and this will sort us out,” was all that he said when he’d made up his mind which day was for slaughtering. His face was flat and there was a bad quietness at the table. I stirred my soup round and round with my spoon. “There will be enough left over,” my mother said as she stood up and returned to the weaving, but it sounded more like a question, as if she were asking for something. Her hands rubbed up and down her overskirt before she picked up the shuttle. I fear that any day now we could come downstairs to find large men in dark clothes blocking the light from the open door: one writing notes with a long plumy pen and the other pointing directions while the rooms are emptied and our belongings piled outside in the lane.

But I am not myself. The sickness and bad temper that has been causing me trouble for the last few weeks is rising as usual and will last for hours. I squat by the hearth, laying the logs over the spitting hot brash without burning my fingers. Hester is fretting. Her mouth is sore as her teeth push themselves up in her gums, and she is still missing her sister. Ann began to work at Wiston House two months ago and she has not been forgiven for leaving us here, but only Hester is allowed to voice her feelings. My own fury is absorbed into the house by other means.

Other books

Seize the Booty! (Erotica Arcanus) by Wellington, E.E.

After the Wreck, I Picked Myself Up, Spread My Wings, and Flew Away by Joyce Carol Oates

Conduit by Angie Martin

Meant to Be by Melody Carlson

Detection by Gaslight by Douglas G. Greene

Cobweb Forest (Cobweb Bride Trilogy) by Nazarian, Vera

TROUBLE, A New Adult Romance Novel (The Rebel Series) by Casey, Elle

Topped Chef A Key West Food Critic Mystery by Lucy Burdette

Bone in the Throat by Anthony Bourdain

No Coming Back by Keith Houghton