The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (10 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

5.97Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Her reflection sat in the vanity mirror across from her, also thinking. Wondering if reflections worked the same way the paintings did, Olive put on the spectacles and walked into the vanity mirror. All she got was a bumped nose.

She wandered down to the library, where her father was frowning at the computer. “Hello, Olive,” he said, glancing up. “Is it dinnertime already?”

“It’s three thirty,” said Olive.

“Ah.” Mr. Dunwoody looked back down at the computer screen. “It’s been a long afternoon.”

Olive moseyed out onto the porch. The summer day was warm, with moist air making the ferns uncurl happily. The rusty chains on the porch swing creaked in the breeze. She glanced across the yard at Mrs. Nivens’s house. It looked very different from the house in the painting. The gate where Morton swung wasn’t there. The fence around the yard had disappeared. Instead of tinted gray by evening light, the house was white and gleaming. Neat lace curtains hung in its windows. It was funny, Olive thought. Even though nothing about the house itself had changed, it looked like a different place entirely.

Olive moved through the shade along the side of the house to the backyard, where the thick lilac clumps in the hedges were already turning from purple to brown, and shuffled her feet in the dewy grass. She could hear voices coming through the hedge—women’s voices.

Olive peeped through the lilac bushes and into Mrs. Nivens’s backyard. It was almost as different from the Dunwoodys’ as two yards could be. While the Dunwoodys’ was shady and overgrown with tangles of ivy and ferns, Mrs. Nivens’s yard had a few carefully tended trees, some tulips growing in strict rows, and grass that looked like it might have been combed and trimmed by hand. A TV commercial would have looked just right in Mrs. Nivens’s yard. A dinosaur would have looked just right in the Dunwoodys’.

Mrs. Nivens was sitting with Mrs. Dewey, who lived one house over, beneath the striped umbrella of her little white picnic table. When Olive approached, Mrs. Dewey was talking.

“Well, that’s not what Ned Hanniman told me. He’s got a perfect view from right across the street, and he said they haven’t brought a thing out of that house. It’s all still in there.”

Olive edged closer, leaning into the lilac bushes.

“I’m sure they just don’t know,” sighed Mrs. Nivens. “How would they? They don’t bother to talk with their neighbors. If I hadn’t gone over there and introduced myself, we wouldn’t even know their names.”

“Sad, isn’t it?” Mrs. Dewey shook her head.

“But you know, I personally wouldn’t want to live surrounded by all that old stuff. Dusty furniture and paintings and—”

Mrs. Nivens and Mrs. Dewey jumped. Olive had leaned forward just a smidge too far and toppled over into the lilacs.

“Olive?” Mrs. Nivens squinted toward the rustling hedge. “Is that you, dear?”

“Um . . .” said Olive.

“Why don’t you come over here and sit with us?” Mrs. Nivens turned back toward Mrs. Dewey. “Lydia, this is Olive Dunwoody, our new neighbor.”

Olive, sure that her face was bright pink, squished herself between the bushes and stumbled into the Nivenses’ yard.

Mrs. Nivens and Mrs. Dewey both smiled at her sweetly. Mrs. Dewey looked as if she had been made of round parts stacked on top of each other, like a snowman. Mrs. Nivens was thin and blond, and looked like she had been carved out of a stick of butter. Both of them looked like they would melt on a hot day.

“We were just talking about your house,” said Mrs. Dewey in a sugary voice.

“Yes.” Mrs. Nivens took over. “The McMartins were a very unusual family.” Mrs. Nivens said the word

unusual

the way most people said the word

manure.

“I’m sure the inside of the house is just as interesting as the outside.”

Interesting

sounded like

manure

too.

unusual

the way most people said the word

manure.

“I’m sure the inside of the house is just as interesting as the outside.”

Interesting

sounded like

manure

too.

“Uh-huh,” said Olive. “It’s interesting.”

“That house used to be quite well-known around here,” said Mrs. Dewey. “The man who built it, Aldous McMartin, was a rather famous painter in his time.”

“Yes.” Mrs. Nivens took over again. “But they say he never sold a single painting. He wouldn’t let anyone buy them. That’s part of why he became famous—for being so odd. Now and then he’d let people into the house to see the paintings. But for some reason he wouldn’t sell a single one.”

Somewhere in the back of Olive’s mind, a few more puzzle pieces clicked together. If Aldous McMartin wouldn’t sell his paintings, it was probably because he knew that they were not ordinary paintings. Maybe he had made them that way himself. Olive’s thoughts spiraled like bubbles around a bathtub drain, faster and faster. Was Aldous McMartin the man Morton was talking about? And the girls in the meadow? And the three builders?

Olive was gazing into the distance with her mouth partly open when she realized that Mrs. Nivens and Mrs. Dewey were staring at her with concerned expressions.

Olive started. “I’m sorry. What?”

“I asked,” Mrs. Dewey said slowly, “are your parents doing a lot of redecorating? It’s such an old-fashioned place, with so many strange things that could be brought up-to-date . . .”

“No,” said Olive. “We kind of like it the way it is.” And as soon as she said it, she realized that it was true. Their house was much more interesting than any beige two-bedroom apartment. It was more interesting than anyplace Olive had ever been.

Mrs. Nivens and Mrs. Dewey exchanged significant looks.

“Well, I’d better be going.” Olive stood up. “Oh, by the way,” she said as casually as she could, “did either of you ever know a little boy named Morton who lived around here?”

Mrs. Dewey pursed her lips and frowned slightly. She looked like someone trying to remember the title of a song she hasn’t heard in years. But Mrs. Nivens had turned slightly pale—even paler than usual, that is. She sat stiffly, staring at Olive.

“I can’t remember anyone with that name, I’m afraid,” said Mrs. Dewey.

“No. I don’t think so,” said Mrs. Nivens. She gave Olive a tight little smile. “Perhaps a very long time ago.”

For a moment, Olive could barely breathe. Yes, a very long time ago.

Mrs. Nivens was still staring at her.

“Oh,” said Olive, stretching her mouth into what she hoped was a cheery smile. “Thanks anyway.” Then she hurried back through the lilac hedge into her own shady yard.

She stumbled into the garden, dazed and dizzy. There was something Mrs. Nivens wasn’t telling her. But she and Mrs. Dewey had certainly told her a lot of other things. If Aldous McMartin had done the paintings, maybe he had made them on purpose so that they could be used with the spectacles . . . But Leopold said that the spectacles had belonged to Ms. McMartin. And why would Mr. McMartin have made paintings that people could climb into anyway? Olive twiddled a strand of hair and gazed thoughtfully around the yard.

The backyard garden, a big plot between the crumbling shed and a gigantic oak tree, looked jumbled and overgrown, especially compared to Mrs. Nivens’s neat rows of tulips. Olive knelt down in the dirt, but she couldn’t tell which plants were weeds and which ones weren’t. There were all kinds of strange plants here: plants with purple velvet leaves; plants with tiny red flowers like droplets of blood; plants that looked like open, toothy mouths. She thought she recognized basil and parsley, and something else that looked like mint, but it could just as easily have been a nettle. Tentatively, Olive yanked up one weedy-looking sprout and received a red welt on her thumb.

Sucking on the sore spot, Olive looked around the garden. Could it really have happened the way Morton said? On one night, a long time ago, did he wander out of the house next door and into this yard, perhaps to this very spot . . .

It was a steamy day, but Olive felt a sudden chill trickle down her back. Somebody was watching her.

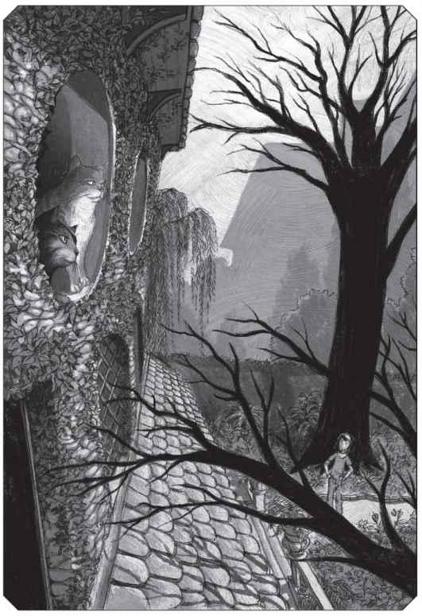

She looked up. The three stories of the old house stared down at her. Somehow she had never noticed the third story at all. From the front of the old stone house, a person could see only two levels of windows: those on the ground floor, and those upstairs. But here, at the back, something was different. The house’s windows were made in all different shapes and sizes. There were large windows and small windows, dormer windows with panes of leaded glass, and windows with colorful beveled borders. Way up high, in a third story, there were tiny round windows that looked like something from an old sailing ship. And in one of those tiny round windows, there were two cats looking down at her.

Olive blinked. The cats sat still, as cats do when they know that they’ve been spotted. One of them sat mostly in shadow, and the only part of it Olive could see clearly was one bright green eye. The other was large and orange, and very familiar.

Her heart surged. Horatio!

Olive bolted up the steps onto the porch and through the back door. She ran along the hall, grabbed the newel post at the bottom of the stairs to keep from skidding into the parlor, and headed toward the second floor. If there were windows up there, it meant there had to be an attic. And if there was an attic, there had to be a staircase to the attic somewhere, and she was going to find it.

She raced through each upstairs room, searching for the staircase. No luck. She checked the rooms a second time, opening all the closet doors and even looking in drawers and wardrobes, like anyone who has read about Narnia would. She checked every ceiling, making sure there wasn’t some sort of trapdoor or ladder that she could pull down. She tried turning newel posts and pushing squares of wood paneling, hoping that there would be some secret lever or button. But there wasn’t.

Frustrated and confused, Olive thumped slowly back down the stairs. Whether Horatio was hiding from her, or whether the attic itself was keeping some sort of secret, she was being left out. Olive felt miffed. The miffed feeling grew into a feeling of annoyance, which grew into a feeling that was almost fury. This house was trying to exclude her. But instead of quietly skulking away, as Olive usually did when she was left out, she looked around for something to kick. She gave the wall that ran up the staircase a quick boot, and then felt immediately sorry. It wasn’t the wall’s fault. But before she had time to make amends, something strange caught her eye.

Halfway down the staircase, just to Olive’s right, hung a painting that she had noticed many times. It was an outdoor scene: a small, silver lake under a twilit sky. But this time, as Olive passed the painting, something within it sparkled, catching a beam of light. Olive put on the spectacles. The painted pine trees waved their branches cheerily. The silver water rippled onto the sand. A star or two peeked through the sky. And something small, bright, and gold glittered in the water just beyond the shore. Olive peered at it more closely. Yes, there was absolutely something there.

For a split second, Olive thought about the shadows that had chased her through the forest. She thought about Morton. She thought about Annabelle. And she thought about Horatio. Perhaps Horatio just wanted to scare her. Perhaps he had some reason for wanting to keep her from finding out the truth. Morton hadn’t trusted him. Maybe Olive shouldn’t either. She wasn’t going to let some bossy cat tell her what she could do and where she could go in her own house. With a careful glance around to make sure her parents were nowhere in sight, Olive heaved herself into the picture frame.

Reeds whispered softly around her ankles. Bits of sand slipped through her socks and lodged themselves between her toes. Olive could smell the lake’s fishy, warm scent, laced with a whiff of spicy pine.

She walked toward the water. Where the reeds dissolved into a swath of sand, Olive peeled off her socks and rolled up her jeans. The water was the temperature of warm soda pop or cold soup. Olive waded along in the shallow places, hoping to spot the gold thing in the very shallowest water—preferably, right on the sand.

A few feet farther into the lake, something glittered. Olive sighed. The purplish water went over her knees, up to her waist. She tried to grab the gold thing with her toes, but it slipped out of their grip every time. She could feel it, though—something small and cold and hard. She wasn’t going to quit until she knew just what it was. Finally, Olive took a big gulp of air, held on to the spectacles with one hand, squinched her eyes shut, and plunged down under the water.

Other books

Harry's Game by Seymour, Gerald

The Red Bikini by Lauren Christopher

Flame Unleashed (Hell to Pay) by David, Jillian

Call to Duty by Richard Herman

Extreme Fishing by Robson Green

Hurt by Tabitha Suzuma

Death Has Deep Roots by Michael Gilbert

Nemesis by Jo Nesbø

The Orkney Scroll by Lyn Hamilton

Touch of Eden by Jessie M.