The Borrowers Aloft (2 page)

Read The Borrowers Aloft Online

Authors: Mary Norton

Chapter Two

Mr. Pott had never heard of Mr. Platter, nor Mr. Platter of Mr. Pott.

Mr. Platter was a builder and undertaker at Went-le-Craye, the other side of the river, of which Mr. Pott's stream was a tributary. They lived quite close, as the crow flies, but far apart by road. Mr. Platter had a fine, new red-brick house on the main road to Bedford, with a gravel drive and a garden that sloped to the water. He had built it himself and called it "Ballyhoggin." Mr. Platter had amassed a good deal of money. But people weren't dying as they used to, and when the brick factory closed down, there were fewer new inhabitants. This was because Mr. Platter, building gimcrack villas for the workers, had spoiled the look of the countryside.

Some of Mr. Platter's villas were left on his hands, and he would advertise them in county papers as "suitable for elderly retired couples." He was annoyed if, in desperation, he had to let to a bride and bridegroom because Mr. Platter was very good at arranging expensive funerals and he liked to stock up on an older type of client. He had a tight kind of face and a pair of rimless glasses, which caught the light so you could not see his eyes. He had, however, a very polite and gentle manner, so you took the eyes on trust. Dear Mr. Platter, the mourners said, was always "so very kind," and they seldom questioned his bill.

Mr. Platter was small and thin, but Mrs. Platter was large. Both had rather mauvish faces: Mr. Platter's had a violet tinge; Mrs. Platter's inclined more to pink. Mrs. Platter was an excellent wife, and both of them worked very hard.

As villas fell vacant and funerals became scarcer, Mr. Platter had time on his hands. He had never liked spare time. In order to get rid of it, he took up gardening. Al! Mr. Platter's flowers were kept like captives—firmly tied to stakes; the slightest sway or wriggle was swiftly punished. A lop here or a cut there and the bullied plants gave in: uncomplaining as guardsmen, they would stand to attention in rows. His lawns, too, were a sight to behold as, weed-repelled and mown in stripes, they sloped down to the river. A glimpse of Mr. Platter with his weeding tools was enough to make the sliest dandelion seed smartly change course in mid-air, and it was said of a daisy plant that, realizing suddenly where it was, the pink-fringed petals turned white overnight.

Mrs. Platter, for her part—and with an eye to the main road and its traffic—put up a notice that said, "TEAS," and she set up a stall on the grass verge for the sale of flowers and fruit. They did not do very well, however, until Mrs. Platter had an inspiration and changed the wording of the notice to "RIVERSIDE TEAS." Then people did stop. And once conducted to the tables behind the house, they would have the "set tea" because there was no other. This was expensive, although there was margarine instead of butter and falsely pink, oozy jam bought by Mrs. Platter straight from the factory in large tin containers; she also sold soft drinks in glass bottles with marble stoppers, toy balloons, and paper windmills. People kept coming, and the Platters began to do well; the cyclists were glad to sit down for a while, and the motorists to take off their dust coats and goggles and stretch their legs.

The falling off was gradual. At first, they hardly noticed it. "Quiet Whitsun," Mr. Platter would say as they changed the position of the tables so as not to damage the lawn. He thought again about an ice-cream machine but decided to wait: Mr. Platter was a great believer in what he described as "laying out money" but only where he saw a safe return.

Instead of this, he mended up his old flat-bottomed boat, and with the aid of a shrimping net, he cleared the stream of scum. "Boating" he wanted to add to the tea notice; but Mrs. Platter dissuaded him. There might be complaints, she thought, as with the best will in the world and a bit of pulling and pushing, you could get the boat around the nettle-infested island but that would be about all.

August Bank Holiday was a fiasco: only ten "set teas" on what Mrs. Platter called "The Saturday," eleven on the Sunday, and seven on the Monday. "I can't make it out," Mrs. Platter kept saying, as she and Agnes Mercy threw the stale loaves into buckets for the chickens. "Last year, they were standing for tables ..."

Agnes Mercy was fifteen now. She had grown into a large, slow, watchful girl, who seemed older than her age. This was her first job—called "helping Mrs. Platter with the teas."

"Mrs. Read's doing teas too now," said Agnes Mercy one day when they were cutting bread and butter.

"Mrs. Read of Fordham? Mrs. Read of the Crown and Anchor?" Mrs. Platter seldom went to Fordham—it was what she called "out of her way."

"That's right," said Agnes Mercy.

"Teas in the garden?"

Agnes Mercy nodded. "And in the orchard. Next year they're converting the barn."

"But what does she give them? I mean, she hasn't got a river. Does she give them strawberries?"

Agnes Mercy shook her head. "No," she said, "it's because of the model railway..." and in her slow way, under a fire of questions, she told Mrs. Platter about Mr. Pott.

"A model railway..." remarked Mrs. Platter thoughtfully, after a short reflective silence. "Well, two can play at that game!"

Mr. Platter whipped up a model railway in no time at all. There was not a moment to lose, and he laid out money in a big way. Mr. Pott was a slow worker, but he was several years ahead. All Mr. Platter's builders were called in. A bridge was built to the island; the island was cleared of weeds; paths and turf were laid down, electric batteries installed. Mr. Platter went up to London and bought two sets of the most expensive trains on the market, freight and passenger. He bought two railway stations, both exactly alike, but far more modern than the railway station at Little Fordham. Experts came down from London to install his signal boxes and to adjust his lines and points. It was all done in less than three months.

And it worked. By the very next summer, to "RIVERSIDE TEAS" they added the words "MODEL RAILWAY."

And the people poured in.

Mr. Platter had to clear a field and face it with rubble for parking the motorcars. In addition to the "set teas," it cost a shilling to cross the bridge and visit the railway. Halfway through the summer, the paths on the island became worn down, and he refaced them with asphalt and built a second bridge to keep people moving. And he put the price up to one and sixpence.

There was soon an asphalted parking place and a special field for wagonnettes and a stone trough with running water for the horses. Parties would often picnic in this field, leaving it strewn with litter.

But none of this bothered Mr. Pott. He was not particularly anxious for visitors: they took up his time and disturbed his work. If he encouraged sight-seers at all, it was just out of loyalty to his beloved Railway Benevolent.

He took no precautions for their comfort, however. It was Mrs. Read of the Crown and Anchor who saw to that side of things and who benefitted accordingly. The whole of Mr. Pott's railway could be seen from the back doorstep, which led on to his garden, and sight-seers had to pass through his house. They were welcome, of course, as they went through the kitchen to a glass of cool water from the tap.

When Mr. Pott built his church, it was an exact copy of the Norman church at Fordham, with added steeple, gravestones, and all. He collected stone for over a year before he started to build. The stone breakers helped him, as they chipped beside the highway. So did Mr. Flood, the mason. By now Mr. Pott had several helpers in the village: besides Henry the blacksmith, he had Miss Men-zies of High Beech. Miss Menzies was very useful to Mr. Pott. She designed Christmas cards for a living, wrote children's books, and her hobbies were wood carving, hand weaving, and barbola

*

work. She also believed in fairies.

When Mr. Platter heard of the church—it took some time, because, until it was finished, during visiting hours Mr. Pott swathed it in sacking—Mr. Platter put up a larger one with a much higher steeple, based on Salisbury Cathedral. At a touch the windows lit up, and with the aid of a phonograph he laid on music inside. Takings had fallen off again slightly at Ballyhoggin; now they leaped up.

All the same, Mr. Pott was a great worry to Mr. Platter—you never quite knew what he might be up to in his gentle, plodding way. When Mr. Pott built two cob cottages and thatched them, Mr. Platter's takings fell off for weeks. Mr. Platter was forced to screen off part of his island and build, at lightning speed, a row of semidetached villas and a public house. The same thing happened when Mr. Pott built his village shop and filled the window with miniature merchandise in painted barbola work—a gift from Miss Menzies of High Beech. Immediately, of course, Mr. Platter built a row of shops and a hairdresser's establishment with a striped pole.

After a while, Mr. Platter found a way of spying on Mr. Pott.

Chapter Three

He mended up the flat-bottomed boat, which, for lack of use, had again become waterlogged.

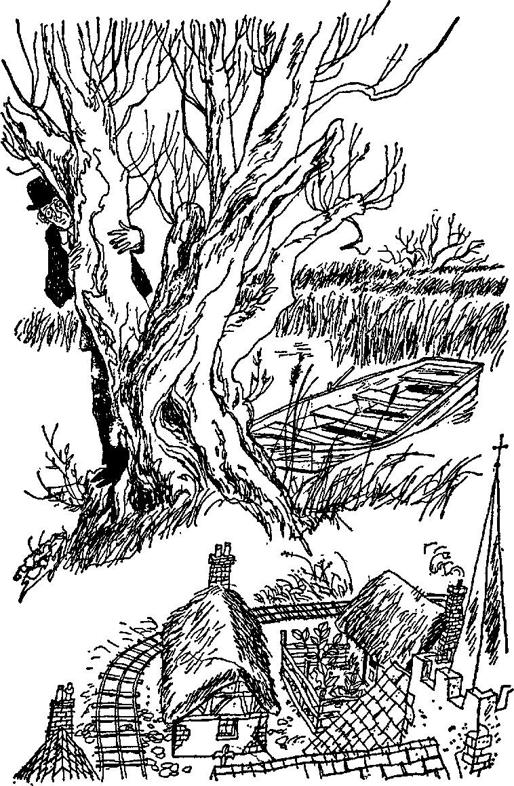

Between the two villages, the weed-clogged river and its twisting, deep-cleft tributaries formed an irritating network, only to be detoured by roads to distant bridges or by clambering and wading on foot. But if, thought Mr. Platter, you could force a boat through the rushes, you had a short cut and could spy on Mr. Pott's house through the willows by his stream.

And this he did—after business hours on summer evenings. He did not like these expeditions but felt them to be his duty. Plagued by gnats, stung by horseflies, scratched by brambles, when he arrived back to report to Mrs. Platter, he was always in a very bad temper. Sometimes he got stuck in the mud, and sometimes, when the river was low, he had to clamber out into slime and frogs' spawn to lift the boat over hidden obstructions such as drowned logs or barbed wire. But he found a

place, a little past the poplars, where, standing on the stump of a willow, he could see the whole layout of Mr. Pott's model village.

"You shouldn't do it, love," Mrs. Platter would say when—panting, puce, and perspiring—he sank on a bench in the garden. "Not at your age and with your blood pressure." But she had to agree as she dabbed his gnat bites with ammonia or his wasp stings with dolly-blue, that taking it by and large his information was priceless. It was only due to Mr. Platter's courage and endurance that they found out about the model stationmaster and about Mr. Pott's two porters and the vicar in his cassock who stood at Mr. Pott's church door. Each of these tiny figures had been modeled by Miss Menzies and dressed by her in suitable clothes, which she oiled to withstand the rain.

This discovery had shaken Mr. Platter. It was just before the opening of the season. "Lifelike," he kept saying, "that's how you'd describe them. Madame Tussaud's waxworks isn't in it. Why anyone of 'em might

speak

to you, if you see what I mean. It's enough to ruin you," he concluded, "and would have if I hadn't seen 'em in time."

However, he

had

seen them in time; and soon both the model villages were inhabited. But Mr. Platter's figures seemed far less real than Mr. Pott's. They were hurriedly modeled, ready dressed in plaster of Paris and brightly varnished over. To make up for this, they were far more varied, and there were many more of them—postmen, milkmen, soldiers, sailors, and the lately invented boy scouts. On the steps of his church, he put a bishop, surrounded by choirboys. Each of the choirboys looked like the others, each had a hymn book and a white-plaster cassock; all had wide open mouths.

"Now they are what I

would

call lifelike..." Mrs. Platter used to say proudly. And the organ would boom in the church.

Then came the awful evening, long to be remembered, when Mr. Platter returning from a boat trip, almost stumbled as he climbed back onto the lawn. Mrs. Platter, at one of the tables, her large white cat on her lap, was peacefully counting out the takings; the littered garden was bathed in evening sunlight, and the sleepy birds sang in the trees.

"Whatever's the matter?" exclaimed Mrs. Platter when she saw Mr. Platter's face.

He sank down heavily in the green chair opposite, shaking the table and dislodging a pile of half crowns. The cat, alarmed and filled with foreboding, streaked off toward the shrubbery. Mr. Platter stared dully at the half crowns as they rolled away across the greensward, but he did not stoop to pick them up. Neither did Mrs. Platter; she was staring at Mr. Platter's complexion: it looked most peculiar—a kind of greenish heliotrope, very delicate in shade.

"Whatever's the matter? Go on, tell me! What's he been and done now?"

Mr. Platter looked back at her without any expression. "We're done for," he said.

"Nonsense. What he can do, we can do. And it's always been like that. Remember the smoke. Now come on, tell me!"

"Smoke," exclaimed Mr. Platter bitterly. "That was nothing—a bit of charred string! We soon got the hang of the smoke. No, this is different; this is the end. We're finished," he added wearily.

"Why do you say that?"

Mr. Platter got up from his chair, and mechanically, as if he did not know what he was doing, he picked up the fallen half crowns. He piled them up neatly and pushed the pile toward her. "Got to look after the money now," he said in the same dull, expressionless voice, and he slumped again in his chair.

"Now, Sidney," said Mrs. Platter, "this isn't like you—you've got to show fight."

"No good fighting," said Mr. Platter, "where the odds is impossible. What he's done now is plain straightforward impossible."

His eyes strayed to the island where, touched with golden light among the long evening shadows, the static plaster figures glowed dully, frozen in their attitudes—some seeming to run, some seeming to walk, some about to knock on doors, and others simply sitting. Several windows of the model village glowed with molten sunlight as if they were afire. The birds hopped about amongst the houses, seeking for crumbs dropped by the visitors. Except for the birds, nothing moved ... stillness and deadness...

Mr. Platter blinked. "And I'd set my heart on a cricket pitch," he said huskily, "bowler and batsmen and all."

"Well, we still

can

have," said Mrs. Platter.

He looked at her pityingly. "Not if they don't

play

cricket—don't you understand? I'm

telling

you—what he's done now is plain, straightforward impossible."

"What has he done then?" asked Mrs. Platter in a frightened voice, infected at last by the cat's foreboding.

Mr. Platter looked back at her with haggard eyes. "He's got a lot of live ones," he said slowly.