The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty (68 page)

Read The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty Online

Authors: Caroline Alexander

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #Naval

BOOK: The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty

5.89Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

William Purcell went out to the West Indies after the court-martial; eventually, he would serve in fourteen more ships before retirement. Sometime after 1800, he married Hannah Maria Mayo, a widow. Purcell died in 1834, after having “shown symptoms of derangement,” in Haslar Hospital, across the water from Portsmouth. His death was thought to warrant a notice in the

Gentlemen’s Magazine,

in which he was referred to as “the last surviving officer of the Bounty, and one of those turned adrift in an open boat on the Pacific ocean.” Touchingly, his wife’s grave-stone also commemorated this event, referring to Mrs. Purcell as the relict of one who had been “an adherent of Captain Bligh’s.”

Gentlemen’s Magazine,

in which he was referred to as “the last surviving officer of the Bounty, and one of those turned adrift in an open boat on the Pacific ocean.” Touchingly, his wife’s grave-stone also commemorated this event, referring to Mrs. Purcell as the relict of one who had been “an adherent of Captain Bligh’s.”

Purcell was indeed the last of the officers to die, but the last survivors who had sailed on the

Bounty

were still alive on Pitcairn. Mauatua—Maimiti, Mainmast, “Isabella”—the widow of Fletcher Christian, was to die in 1841, at a very advanced age. White-haired but still mentally alert, she had “frequently said she remembered Captain Cook arriving at Tahiti,” as the Pitcairn Island register recorded. She had, then, seen it all, from the long-ago age of discovery when the white men descended on her island, through the death—or departure—of her famous husband. She was attended by Teraura, the widow of both Edward Young and, spanning two generations, Fletcher’s son, Thursday October Christian. Teraura died in 1850.

Bounty

were still alive on Pitcairn. Mauatua—Maimiti, Mainmast, “Isabella”—the widow of Fletcher Christian, was to die in 1841, at a very advanced age. White-haired but still mentally alert, she had “frequently said she remembered Captain Cook arriving at Tahiti,” as the Pitcairn Island register recorded. She had, then, seen it all, from the long-ago age of discovery when the white men descended on her island, through the death—or departure—of her famous husband. She was attended by Teraura, the widow of both Edward Young and, spanning two generations, Fletcher’s son, Thursday October Christian. Teraura died in 1850.

Bligh himself did not live long enough to see the end of his own story. He had known himself to be “notorious,” and read countless cruel summations of his character that appeared unchecked in every variety of literature. Doubtless he knew he was said to have pushed “the discipline of the service to which he belonged, . . . to its extreme verge . . . goaded into a mutiny a crew of noble-minded fellows, the greater part of whom it has been since discovered, pined away their existence on a desolate island.” In the final telling, he “was an unfeeling tyrant, and induced the mutiny by his harshness and cruelty.” Over the years, Bligh’s “cruelty” would be made brutally physical; a comparison was even made between the necessary atrocities committed by the French revolutionaries and the deeds of the mutineers; “we will merely draw a parallel by observing . . . the

excessive

folly and tyranny of her government.” Lieutenant Bligh, who had hoped to complete the

Bounty

voyage without a single flogging, would be transformed into “Captain Bligh of the

Bounty,

” a sadistic bully who bloodied his men with the lash.

excessive

folly and tyranny of her government.” Lieutenant Bligh, who had hoped to complete the

Bounty

voyage without a single flogging, would be transformed into “Captain Bligh of the

Bounty,

” a sadistic bully who bloodied his men with the lash.

To none of these many specious charges did Bligh pay public attention; instead, he had doggedly carried on, from commission to commission. On hearing of his old commander’s death, George Tobin, now post-captain but a former lieutenant of the

Providence,

wrote to Bligh’s nephew, Francis Godolphin Bond, offering both his condolences and a humane assessment of the man they had both served: “He has had a long and turbulent journey of it,” wrote Tobin, “—no one more so, and since the unfortunate Mutiny in the

Bounty,

has been rather in the shade. Yet perhaps was he not altogether understood. . . . He had suffered much and ever in difficulty by labour and perseverance extricated himself.”

Providence,

wrote to Bligh’s nephew, Francis Godolphin Bond, offering both his condolences and a humane assessment of the man they had both served: “He has had a long and turbulent journey of it,” wrote Tobin, “—no one more so, and since the unfortunate Mutiny in the

Bounty,

has been rather in the shade. Yet perhaps was he not altogether understood. . . . He had suffered much and ever in difficulty by labour and perseverance extricated himself.”

Bligh was buried beside his wife in the same tomb in St. Mary’s churchyard, Lambeth. Over the years, the churchyard fell out of use and became overgrown, and eventually was used as a rubbish dump. At length, some 170 years after Bligh’s death, a renovation was begun and the covered graves and tombs at last dug out. In clearing the ground, excavators moved a large oblong block—and found themselves looking at the entrance to a vault. Four steps led down into an arched brick chamber, where stood a number of lead coffins, embellished with garlands and swags. The two standing side by side, less than two feet apart, contained the remains of William and Betsy Bligh, while tiny coffins at the back held the remains of twin sons, who had lived but a single day. The wooden coffin lids had collapsed, revealing the adult skeletons; that of Bligh still held tufts of mortal hair. Stunned, the intruders quickly conferred; photographs of Captain Bligh of the

Bounty

would fetch a very good price . . .

Bounty

would fetch a very good price . . .

“No,” recalled one, “we couldn’t possibly do it.” Replacing the lids, they exited the vault, and sealed it. (Duty; they had done their duty. . . . )

Cleared and scrubbed, the inscription on the handsome monument could be read again. Beneath a miniature graven shield, crested with a knight’s hand holding a battle axe, read a succinct summation of Bligh’s life:

Sacred

to the memory of

William Bligh, Esquire, F.R.S.

Vice Admiral of the Blue,

The celebrated Navigator

who first transplanted the Bread Fruit Tree

From Otaheite to the West Indies,

bravely fought the battles of his country;

and died beloved respected and lamented

on the 7th day of December 1817

aged 64.

Surmounting the whole, in letters that had once been gold, was a simple phrase:

“In coelo quies”

—There is peace in heaven.

A NOTE ON SOURCES

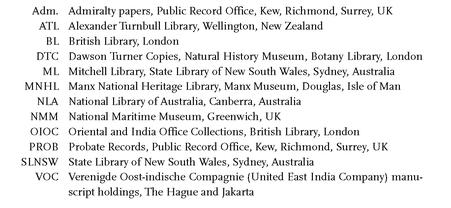

ABBREVIATIONS

All of the correspondence quoted is held by the Mitchell Library (hereafter ML), State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia (hereafter SLNSW). That with Duncan Campbell is found at “William Bligh, Letters 1782-1805,” Safe 1/40 (letters of December 10, 1787; December 22, 1787; January 9, 1788; February 17, 1788; May 20, 1788). Bligh’s correspondence with Banks is found in SLNSW: the Sir Joseph Banks Electronic Archive (February 17, 1788, Series 46.21). Bligh’s letter to his wife from Coupang is found in ML, “Bligh, William—Family correspondence,” ZML Safe 1/45, pp. 17-24.

Bligh’s correspondence from the Dutch East Indies to Campbell, Banks, and Elizabeth Bligh is published in facsimile in Paul Brunton, ed.,

Awake Bold Bligh!

(Sydney, 1989).

PANDORAAwake Bold Bligh!

(Sydney, 1989).

The descriptions of Peter Heywood’s last day on Tahiti and his capture are found in a letter to his mother, written in Batavia on November 20, 1791, and preserved in an album of correspondence relating to his court-martial that was kept by his sister Hester (Nessy) Heywood. There are five known copies of this album; the one cited throughout this book is “Correspondence of Miss Nessy Heywood,” E5. H5078, the Newberry Library, Chicago. This is also the source for Peter Heywood’s poetry. Peter’s Isle of Man tattoo is referred to by William Bligh in his descriptive list of the mutineers, of which there are several versions; the earliest being that given in his notebook, held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra (NLA MS 5393) and published in facsimile, John Bach, ed.,

The Bligh Notebook

(Sydney, 1987). Other details about the mutineers—their ages and places of origin—are taken from the

Bounty

Muster Book, Admiralty papers, Public Record Office (hereafter Adm.) 36/10744.

The Bligh Notebook

(Sydney, 1987). Other details about the mutineers—their ages and places of origin—are taken from the

Bounty

Muster Book, Admiralty papers, Public Record Office (hereafter Adm.) 36/10744.

Early news of the mutiny is found in numerous contemporary newspapers:

English Chronicle or Universal Evening Post

(March 13-16, 1790), the

General Evening Post

(March 16- 18, 1790), the

London Chronicle

(March 16, 1790) and the

World

(March 16, 1790), to cite only a few. The possibility of the

Bounty

’s being apprehended by the Spanish is reported in

British Mercury,

no. 20, May 15, 1790 (p. 212). The report that news of the

Bounty

mutiny had inspired Botany Bay convicts to attempt escape is found in the

London Chronicle,

April 21-24, 1792.

English Chronicle or Universal Evening Post

(March 13-16, 1790), the

General Evening Post

(March 16- 18, 1790), the

London Chronicle

(March 16, 1790) and the

World

(March 16, 1790), to cite only a few. The possibility of the

Bounty

’s being apprehended by the Spanish is reported in

British Mercury,

no. 20, May 15, 1790 (p. 212). The report that news of the

Bounty

mutiny had inspired Botany Bay convicts to attempt escape is found in the

London Chronicle,

April 21-24, 1792.

The transcription of the court-martial of the mutineers of the

Narcissus

is found in Adm. 12/24, and is in itself fascinating: in 1782, as newly appointed captain to the 20-gun

Narcissus,

Edwards was patrolling the eastern coast of North America when word came through the quartermaster that a mutiny was planned for that night. Swiftly, all officers had armed themselves, come on deck, and together forced the apprehension of the would-be mutineers. In the ensuing court-martial it was revealed that some forty-six men had signed up for the mutiny with the intention of securing the captain in irons and making for “Philadelphia or the first rebel fort.” Once within sight of land, the plan had been to put the captain and officers into the longboat with a compass, sail the ship to port, sell her, and divide the spoils. The code word signifying that the mutiny had commenced was to have been “wine.”

Narcissus

is found in Adm. 12/24, and is in itself fascinating: in 1782, as newly appointed captain to the 20-gun

Narcissus,

Edwards was patrolling the eastern coast of North America when word came through the quartermaster that a mutiny was planned for that night. Swiftly, all officers had armed themselves, come on deck, and together forced the apprehension of the would-be mutineers. In the ensuing court-martial it was revealed that some forty-six men had signed up for the mutiny with the intention of securing the captain in irons and making for “Philadelphia or the first rebel fort.” Once within sight of land, the plan had been to put the captain and officers into the longboat with a compass, sail the ship to port, sell her, and divide the spoils. The code word signifying that the mutiny had commenced was to have been “wine.”

Edwards’s papers are found in Adm. 1/1763, which includes his correspondence with the Admiralty before

Pandora

left England, his long official report, and his official correspondence following his return home. Other pertinent papers are found in Admiralty Library Manuscript MSS 180, “The Papers of Edward Edwards,” held at the Royal Naval Museum and Admiralty Library in Portsmouth (and read on microfilm provided by ML: reel FM4 2098 [AJCP reel M 2515]), which includes the log of the

Pandora

(and of the open-boat journey and voyage to Batavia); Edwards’s extracts from the journals of Peter Heywood and George Stewart; a memorandum written by Edwards at Tahiti; a statement written by Edwards on the loss of the

Pandora;

as well as the original sailing orders he received from the Admiralty and an account of his career. These papers were lost until 1966, having spent many years in a brown-paper parcel in a forgotten corner of the Admiralty Library (H. E. Maude, “The Edwards Papers,”

Journal of Pacific History

1 [1966], pp. 184-85).

Pandora

left England, his long official report, and his official correspondence following his return home. Other pertinent papers are found in Admiralty Library Manuscript MSS 180, “The Papers of Edward Edwards,” held at the Royal Naval Museum and Admiralty Library in Portsmouth (and read on microfilm provided by ML: reel FM4 2098 [AJCP reel M 2515]), which includes the log of the

Pandora

(and of the open-boat journey and voyage to Batavia); Edwards’s extracts from the journals of Peter Heywood and George Stewart; a memorandum written by Edwards at Tahiti; a statement written by Edwards on the loss of the

Pandora;

as well as the original sailing orders he received from the Admiralty and an account of his career. These papers were lost until 1966, having spent many years in a brown-paper parcel in a forgotten corner of the Admiralty Library (H. E. Maude, “The Edwards Papers,”

Journal of Pacific History

1 [1966], pp. 184-85).

Surgeon George Hamilton published his account of the

Pandora

voyage in

A Voyage Round the World, in His Majesty’s Frigate Pandora

(London, 1793). Hamilton’s account and Edwards’s report have been published together as Edwards and Hamilton,

Voyage of H.M.S. “Pandora” Despatched to Arrest the Mutineers of the “Bounty” in the South Seas, 1790-91, Being the Narratives of Captain Edward Edwards, R.N., the Commander, and George Hamilton, the Surgeon

(London, 1915).

Pandora

voyage in

A Voyage Round the World, in His Majesty’s Frigate Pandora

(London, 1793). Hamilton’s account and Edwards’s report have been published together as Edwards and Hamilton,

Voyage of H.M.S. “Pandora” Despatched to Arrest the Mutineers of the “Bounty” in the South Seas, 1790-91, Being the Narratives of Captain Edward Edwards, R.N., the Commander, and George Hamilton, the Surgeon

(London, 1915).

Biographical material about Edwards is found in “The Pandora Again!,”

United Service Magazine,

no. 172 (March 1843), pp. 411-20.

United Service Magazine,

no. 172 (March 1843), pp. 411-20.

The history of seaman John Brown and the

Mercury,

the ship that left him on Tahiti, is found in Lieutenant George Mortimer,

Observations and Remarks Made During a Voyage to the Islands of Teneriffe, Amsterdam, Maria’s Islands Near Van Diemen’s Land, Otaheite, Sandwich Islands, Owhyhee, the Fox Islands on the North West Coast of America, Tinian, and from thence to Canton, in the Brig Mercury, Commanded by John Henry Cox, Esq.

(London, 1791).

Mercury,

the ship that left him on Tahiti, is found in Lieutenant George Mortimer,

Observations and Remarks Made During a Voyage to the Islands of Teneriffe, Amsterdam, Maria’s Islands Near Van Diemen’s Land, Otaheite, Sandwich Islands, Owhyhee, the Fox Islands on the North West Coast of America, Tinian, and from thence to Canton, in the Brig Mercury, Commanded by John Henry Cox, Esq.

(London, 1791).

James Morrison wrote two accounts of the mutiny and its aftermath, both held by the Mitchell Library: an extensive “journal” (about which more later), “Journal on HMS Bounty and at Tahiti, 1792,” ZML Safe 1/42; and the much briefer “Memorandum and particulars respecting the Bounty and her crew,” Safe 1/33.

For the Articles of War, see N. A. M. Rodger,

Articles of War: The Statutes which Governed Our Fighting Navies, 1661, 1749, and 1886

(Homewell, Hampshire, 1982).

Articles of War: The Statutes which Governed Our Fighting Navies, 1661, 1749, and 1886

(Homewell, Hampshire, 1982).

The wreck of the

Pandora

is currently being excavated by the Queensland Museum, Australia; it can be followed online at

www.mtq.qld.gov.au

.

Pandora

is currently being excavated by the Queensland Museum, Australia; it can be followed online at

www.mtq.qld.gov.au

.

The story of the Botany Bay convicts is well told in Frederick A. Pottle’s

Boswell and the Girl from Botany Bay

(London, 1938).

Boswell and the Girl from Botany Bay

(London, 1938).

Edwards’s transactions with the Dutch authorities in the East Indies are documented in manuscript holdings of the Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie (hereafter VOC), or United East India Company. These include ARA VOC 3917, pp. 1841 and 1843; VOC 827 (Resolutions of the Governor General and Council, November 8 and 18, 1791); VOC 3940, pp. 8 verso, 9, 32, 32 verso, and 52 (all in the Algemeen Rijksarchief, The Hague); and the Minuut Resolutie Nov.-Dec. 1791 (in the Arsip Nasional Republik, Jakarta). A glimpse of Edwards’s transactions at the Cape is found in Council of Policy, vol. C 202 Resolutions, Edwards, p. 185, in the Cape Town Archives Repository, Cape Town.

Other books

Mystical Seduction: full-length sensual paranormal romance (The Protectors) by McFalls, Dorothy

Undeniable by Alison Kent

Shared By The Dragon Clan: Part Four by Rosette Bolter

Heart of Avalon (Avalon: Web of Magic #10): by Rachel Roberts

The Red Wolf Conspiracy by Robert V. S. Redick

Nightingales in November by Mike Dilger

The Riddle of Sphinx Island by R. T. Raichev

Hayburner (A Gail McCarthy Mystery) by Crum, Laura

Weddings Bells Times Four by Trinity Blacio

InvitingTheDevil by Gabriella Bradley