The Bridge of San Luis Rey (13 page)

Read The Bridge of San Luis Rey Online

Authors: Thornton Wilder

Tags: #Fiction, #Classics, #Literary, #General

Students of Wilder's life will note that in 1930, however, he returned to teaching, this time at the University of Chicago in a part-time post. Nevertheless, in the classroom and in after-hours with students and colleagues, Wilder re-created a world that he needed and enjoyedâa safe, stable, stimulating base, a comfortable foundation of routine, that allowed him to roam and write, be it novels or plays. “The house

The Bridge

built” in Hamden, Connecticut, in 1929â1930, provided a different and ever more permanent anchorage when he chose to use it. Not until 1941, however, would Wilder's travels take him for the first time to Peru. On February 27, 1958, the Peruvian government honored Wilder for creating more than thirty years earlier the timeless, universal

Bridge of San Luis Rey

.

âTappan Wilder

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Readings

The Opening Lines of

The Bridge:

Two Versions

Â

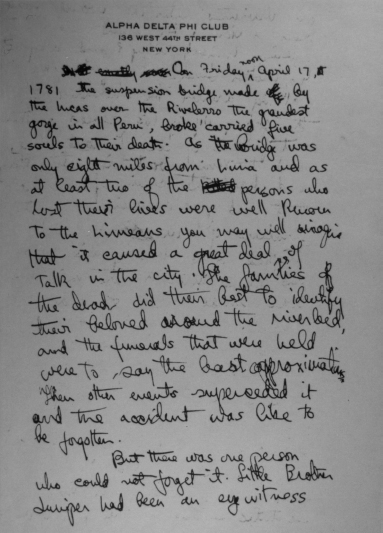

The bridge has no name in this early draftâpossibly the author's first attemptâand written as early as late spring of 1926. He has used his own birth date in this version. The words reveal Thornton Wilder's knowledge of the legendary Incan span. Wilder joined the Alpha Delta Phi Fraternity at Yale and used the facilities of its national clubhouse in New York during the 1920s and early 1930s. The printed text of this letter appears on page 119.

Â

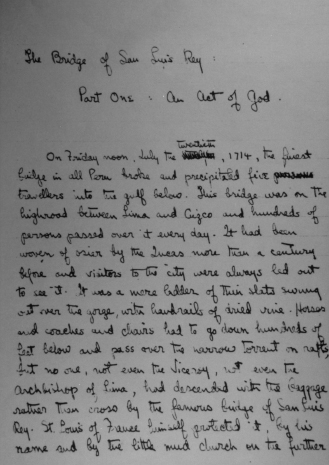

This is Wilder's final handwritten version and is, word for word, what would soon appear in print. In addition to showing changes of date and other details, a comparison to the earlier version reveals how the author labored to achieve the novel's “removed” tone. The printed text of this letter appears on page 119.

Â

Alpha Delta Phi Club

136 West 44th Street

New York

On Friday noon April 17, 1781 the suspension bridge made by the Incas over the Rivelerro the grandest gorge in all Peru, broke carried five souls to their death. As the bridge was only eight miles from Lima and as at least two of the persons who lost their lives were well known to the Limeans you may well imagine that it caused a great deal of talk in the city. The families of the dead did their best to identify their beloved around the riverbed, and the funerals that were held were to say the least approximations. Then other events superceded it and the accident was like to be forgotten.

But there was one person who could not forget it. Little Brother Juniper had been an eyewitness . . .

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

Part One: An Act of God

On Friday noon, July the twentieth, 1714, the finest bridge in all Peru broke and precipitated five travellers into the gulf below. This bridge was on the highroad between Lima and Cuzco and hundreds of persons passed over it every day. It had been woven of osier by the Incas more than a century before and visitors to the city were always led out to see it. It was a mere ladder of thin slats swung out over the gorge, with handrails of dried vine. Horses and coaches and chairs had to go down hundreds of feet below and pass over the narrow torrent on rafts, but no one, not even the Viceroy, not even the Archbishop of Lima, had descended with the baggage rather than cross by the famous bridge of San Luis Rey. St. Louis of France himself protected it, by his name and by the little mud church on the further . . .

Â

Two Entries from Wilder's Journal

Â

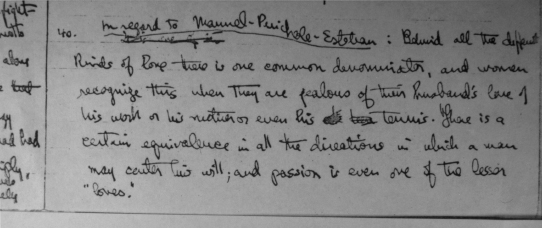

Wilder treated his journal as a private debating society. In these two examples, of which #40 is shown here from the original source, we see him pondering Esteban's personality and the role jealousy plays in love. Wilder did not always date entries, but, to make for efficient reference later on, he was always careful to number them.

Â

37. Esteban's search for death (I have decided to make him much more intelligent than I first planned) is an allegory of what can be done when one has declined living. The steps he takes for release are at first merely physical. (1) rescues from burning houses (2) bullfighting. (3) provoke duels by insulting prominent tyrants etc. His motto was

Je n'existe plus

. N.B. The world seemed to be funnel-shaped and above one's life, unshakable, was the great unwinking eye of God and a voice that said: was that fair? N.B. But when he courted death by taking crazy risks on the side of good the Eye lost its reproach . . . [November? 1926]

Â

40. In regard to Manuel-Perichole-Esteban: Behind all the different kinds of love there is one common denominator, and women recognize this when they are jealous of their husband's love of his work or his mother or even his tennis. There is a certain equivalence in all the directions in which a man may enter his will; and passion is one of the lesser “loves.” [December? 1926]

After Publication

Two Letters

Scores of readers, often students, wrote to Wilder over the years seeking his position on the questions posed in

The Bridge

. In this excerpt from a letter written March 6, 1928, four months after the appearance of the novel, Wilder responds to a query from John Townley, one of his former pupils at Lawrenceville.

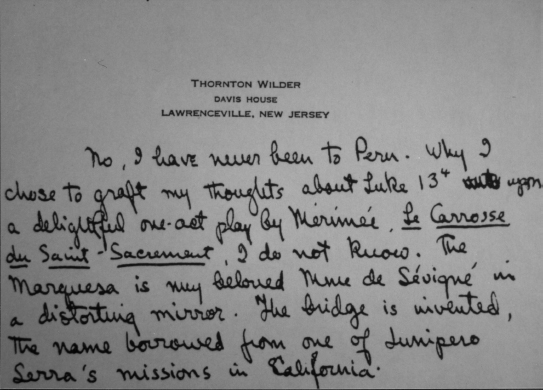

Thornton Wilder

Davis House

Lawrenceville, New Jersey

Dear John:

The book is not supposed to solve. A vague comfort is supposed to hover above the unanswered questions, but it is not a theorem with its Q.E.D. The book is supposed to be as puzzling and distressing as the news that five of your friends died in an automobile accident. I dare not claim that all sudden deaths are, in the last counting, triumphant. As you say, a little over half the situations seem to prove something and the rest escape, or even contradict. Chekhov said: “The business of literature is not to answer questions, but to state them fairly.” I claim that human affection contains a strange unanalyzable consolation and that is all. People who are full of faith claim that the book is a vindication of this optimism; disillusioned people claim that it is a barely concealed “anatomy of despair.” I am nearer the second group than the first; though some days I discover myself shouting confidentially in the first group. Where will I be thirty years from now?âwith Hardy or Cardinal Newman?

Â

Wilder writes to Chauncey Brewster Tinker, a legendary member of Yale's English Department and one of Wilder's college professors. This letter, of which a printed excerpt appears below and a few words in the author's hand here, catches the thirty-year-old author at a moment of doubt about leaving a world in which he excelled and felt at home. Davis House, the dormitory Wilder ran, housed thirty-two students. His father, Amos Parker Wilder (1862â1936), was born in Calais, Maine, and raised in Augusta.

Â

Thornton Wilder

Davis House

Lawrenceville, New Jersey

Dec. 6, 1927

Dear Mr. Tinker:

You may imagine how exciting your letter was for me and how happy and fit-for-nothing it left me the rest of the day. It has decided me to fix on you as the judge in a new problem I have: more and more people are muttering to me that I must leave the little chicken-feed duties of the housemaster and teacher and go to Bermuda, for example, and write books as a cow gives milk. I do not know how to answer them, but I do feel (though with intervals of misgiving) that this life is valuable to me and, I dare presume, my very pleasure in my routine can make it useful to others. Anyway no one, except you and I, seems to believe any longer in the dignity of teaching. (though to us even “dignity” is an understatement.) Ach, you should see the Davis House and all the sincerity and contentment and application that keeps coming out of 32 potential roughnecks and Red Indians. . . .

As for your questions, oh, isn't there a lot of New England in me; all that ignoble passion to be didactic that I have to fight with. All that bewilderment as to where Moral Attitude begins and where it shades off into mere Puritan Bossiness. My father is still pure Maineâ1880âand I carry all that load of notions to examine and discard or assimilate.

No, I have never been to Peru. Why I chose to graft my thoughts about Luke 13 upon a delightful one-act play by Mérimée,

Le Carrosse du Saint-Sacrement

, I do not know. The Marquesa is my beloved Mme. de Sévigné in a distorting mirror. The bridge is invented, the name borrowed from one of Junipero Serra's missions in California. . . .

It is right and fitting that you cried for a page of mine. How many times I have cried with love or awe or pity while you talked of the Doctor, or Cowper, or Goldsmith.

An Interview

The now celebrated author and former teacher has a visit in France on August 18, 1928, with André Maurois, the distinguished French novelist and biographer. As noted, Wilder is about to take a walking trip with the world heavyweight boxing champion, Gene Tunney.

Â

August 18th.âTo-day we had a pleasant visit from Thornton Wilder, the American writer, unknown until his recent fame as the author of

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

. An ingenious theme: the old osier bridge of San Luis Rey, near Lima, breaks one day (about the end of the eighteenth century), just when five people were crossing it. Hurled into the ravine, they perish. An old monk who saw the accident wonders why God sanctioned these deaths, and for the strengthening of his faith he proposes to seek out the causes in the lives of these five people. . . . The sobriety of style reminded one of certain French classics, particularly of Mérimée.

A charming man, quite young. “I'm thirty,” he told me, “like all writers of twenty-six.” He holds a university post.

“My weakness is that I am too bookish,” he said. “I know little of life. I made the characters of

The Bridge

out of the heroes of books. My Marquesa is the Marquise de Sévigné. In my first novel,

The Cabala

, the hero was Keats. The method has served me well, but I don't want to use it again. I shall not write again before I have actually observed men better.”