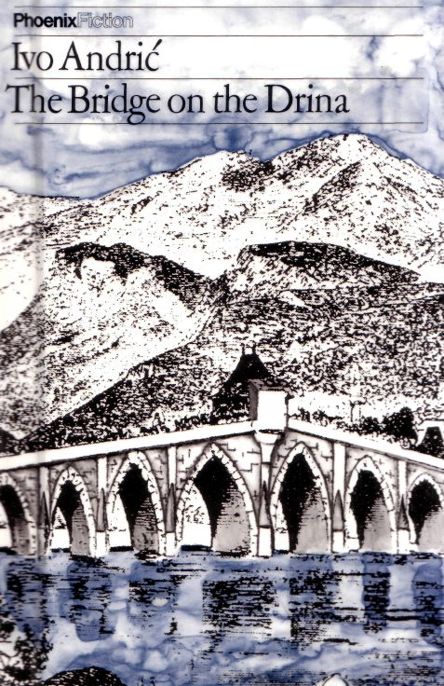

The Bridge on the Drina

Read The Bridge on the Drina Online

Authors: Ivo Andrić

Tags: #TPB, #Yugoslav, #Nobel Prize in Literature, #nepalifiction

IVO ANDRIĆ

THE BRIDGE

ON THE DRINA

Translated from the Serbo-Croat by

LOVETT F. EDWARDS

With an Introduction by

WILLIAM H. MCNEILL

Originally published in 1945

Translation

©

George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1959

Phoenix Edition

/977

ISBN: 0-226-02045-2

Prepared and formatted by

nepalifiction, TPB, 2014

INTRODUCTION

TRANSLATOR'S FOREWORD

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

INTRODUCTION

William H. McNeill

The committee that awarded the Nobel prize for literature to Ivo Andric in 1961 cited the epic force of

The Bridge on the Drina,

first published in Serbo-Croat in 1945, as justification for its award. The award was indeed justified if, as I believe,

The Bridge

on

the Drina

is one of the most perceptive, resonant, and well-wrought works of fiction written in the twentieth century. But the epic comparison seems strained. At any rate, if the work is epic, it remains an epic without a hero. The bridge, both in its inception and at its destruction, is central to the book, but can scarcely be called a hero. It is, rather, a symbol of the establishment and the overthrow of a civilization that came forcibly to the Balkans in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries and was no less forcibly overthrown in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That civilization was Ottoman—radically alien to, and a conscious rival of, both Orthodox Russia and the civilization of western Europe. It was predominantly Turkish and Moslem, but also embraced Christian and Jewish communities, along with such outlaw elements as Gypsies. All find a place in Andric's book; and with an economy of means that is all but magical, he presents the reader with a thoroughly credible portrait of the birth and death of Ottoman civilization as experienced in his native land of Bosnia.

No better introduction to the study of Balkan and Ottoman history exists, nor do I know of any work of fiction that more persuasively introduces the reader to a civilization other than our own. It is an intellectual and emotional adventure to encounter the Ottoman world through Andric's pages in its grandoise beginning and at its tottering finale. Every episode rings true, from the role of terror in fastening the Turkish power firmly on the land to the role of an Austrian army whorehouse in corrupting the old ways. No anthropologist has ever reported the processes of cultural change so sensitively,- no historian has entered so effectively into the minds of the persons with whom he sought to deal. It is, in short, a marvelous work, a masterpiece, and very much

sui generis.

Perhaps a few remarks about Bosnia and its history may be helpful for readers who approach this work without prior acquaintance with the Balkan scene. Bosnia is a mountainous region in the central part of Yugoslavia. Today it is one of the constituent republics of that federal state. In medieval times it broke away from the Kingdom of Serbia in a.d. 960 and thereafter became more or less independent, though perpetually subject to rival jurisdictional claims because of its borderland position between Orthodox and Latin Christendom. In the twelfth century, the ruler of Bosnia sought to assert a fuller independence by becoming a Bogomil. This was a religion, related to Manichaeism, that spread also to western Europe where it was

known as Albigensianism. Many Bosnians followed their ruler's example, remaining heretics in the eyes of their Christian neighbors until after the Turkish conquest, when nearly all of the Bogomils became Moslem. As a result, about one-third of the population of Bosnia is Moslem today, even though they speak a Slavic language, Serbo-Croat, as their ancestors had done back to Bogomil days.

The Turks conquered Bosnia between 1386 and 1463. Conversion to Islam proceeded rather rapidly, especially among the land-owning families of Bosnia; and with religious conversion went a cultural transformation that made Bosnia an outpost of Ottoman civilization. From the fifteenth century onwards, Bosnian military manpower reinforced Ottoman armies. Year after year, Moslem warriors answered the summonses of local governors to go raiding into Christian lands to the north and west. Simultaneously, at irregular intervals agents from Constantinople chose Christian peasant conscripts to replenish the ranks of the sultan's personal household. These recruits were officially classed as slaves, and in addition to military service in the Janissary corps many performed menial services in and around the court. Some, however, after appropriate training, emerged as the topmost military administrators and commanders of the Ottoman armies. A select few rose to the supreme administrative post of grand vizier.

Andric's story of how the bridge was built is completely historical. A Bosnian peasant's son, Muhammad Sôkôllu (né Sokolović) became grand vizier in 1565, and as such governed the empire until his death in 1579. Having been recruited into the sultan's service as a youth, he remembered well his Bosnian birth, and among other acts acknowledging his origins, he chose his own blood brother to become patriarch of the Serbian church. The construction of the bridge across the Drina was another, similar act emanating from the grand vizier's desire to be remembered in the place of his birth.

Ever since the Turkish conquest, Bosnian society had comprised a complex intermingling of Moslems, Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians. As long as Turkish power remained secure, local Moslem dominance was assured, both by the prowess of Moslem landowners and by the sporadic force Ottoman armies could bring to bear against any outside challenge. As Ottoman power diminished, however, and the might of adjacent Christian empires correspondingly increased, the religious divisions of Bosnian society became potentially explosive. Revolt by an oppressed Christian peasantry could expect to win sympathy abroad, either in Russia (for the Orthodox) or in Austria (for Roman Catholics). Simultaneously, mounting population pressure made it harder and harder for the peasantry to maintain traditional standards of living. On top of this, early in the nineteenth century, a handful of intellectuals, educated in Germany, picked up the idea that nationhood and language belonged together and could only attain full perfection within the borders of a sovereign, independent state. Since existing literary languages did not define clear boundaries

between the Slavic dialects spoken in Balkan villages, the ideal of linguistic nationalism intensified confusion in the older religiously structured (and divided) society by offering individuals alternative loyalties and principles of public identity.

These circumstances provided the background for the "Eastern question" that so bedeviled nineteenth-century European diplomats. Bosnia played a conspicuous role. First it was Moslems who revolted against Constantinople (1821, 1828, 1831, 1838-50) in a vain effort to defend their accustomed privileges. Soon after their reactionary ideals had met final defeat (1850), through military conquest by reformed (i.e., partially westernized) Ottoman armies, Christian peasants of Bosnia, objecting to an intensified tax burden brought on by a modernized administration, took up the standard of revolt (1862, 1875-78). This, in turn, provoked intervention by the Christian powers of Europe, with the result that at the Congress of Berlin (1878), Bosnia and the adjacent province of Herzegovina were placed under an Austrian protectorate. A generation later, in 1908, the Austrians announced the annexation of these two provinces to the Hapsburg crown. This precipitated a diplomatic crisis that was part of the prologue to World War I; and, of course, that war was itself occasioned by the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, by Bosnian revolutionaries who wanted their land to become part of Serbia. After 1918, they had their way, for Bosnia was incorporated into the new south Slav kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. During World War II, Bosnia, because of its mountainous character, became Tito's principal stronghold, and after 1945 it was made one of the six constituent republics of the new federal Yugoslav state.

Ivo Andric was born in Travnik, Bosnia, in 1892, but he spent his first two years in Sarajevo, where his father worked as a silversmith. This was a traditional art, preserving artisan skills dating back to Ottoman times; but taste had changed and the market for the sort of silverwork Ivo's father produced was severely depressed. The family therefore lived poorly; and when the future writer was still an infant, his father died, leaving his penniless young widow to look after an only child. They went to live with her parents in Visegrad on the banks of the Drina, where the young Ivo grew up in an artisan family (his grandfather was a carpenter) playing on the bridge he was later to make so famous, and listening to tales about its origin and history which he used so skillfully to define the character of the early Ottoman presence in that remote Bosnian town. The family was Orthodox Christian, i.e., Serb; but in his boyhood and youth Andric was thrown into intimate contact with the entire spectrum of religious communities that coexisted precariously in the Bosnia of his day; and his family shared the puzzling encounter with a strange new Austrian world that he portrays so sensitively in

The Bridge

on

the

Drina.

The young Andric returned to Sarajevo to attend secondary school, and there became a nationalist revolutionary. This did not prevent

him from attending Hapsburg universities, at Zagreb, Cracow, Vienna, and Graz; but with the outbreak of World War I his political activity caused the Austrian police to arrest him. Andric therefore spent the first three years of World War I in an internment camp, where he wrote his first successful book, published in 1918. On release (1917) he took an active part in conducting a literary review that advocated the political union of all south Slav peoples, and he had a minor part in the political transactions that brought Croatia into the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes that emerged in December, 1918.