The Brightonomicon (Brentford Book 8) (12 page)

Read The Brightonomicon (Brentford Book 8) Online

Authors: Robert Rankin

‘All men are b*st*rds!’ the nurse declared.

‘She speaks the fairy tongue, too,’ I said, hoping to inject a little humour into the situation.

But failing miserably.

Hey, a little sympathy, please – my life was at stake here.

And so I fought, and struggled and fought and the trolley (or gurney, or big-push-along-blong-him-all-ouch, or the chromium-plated chariot of Ra, to those who have really given the magic mushrooms a hammering) fell over on to the doctor and the nurse, which at least let me get my legs free.

And

Crash!

went something into the side of the van.

And, ‘It’s a Horseman of the Apocalypse!’ went the driver, who really

had

given the mushrooms a hammering,

and

they were kicking in.

It was all rough and tumble in that van. I punched at the doctor and at the nurse. The doctor punched me and the nurse still had

that hypo.

I was impressed by the way she had managed to hang on to it throughout all the to-ing and fro-ing. But not happy that she had.

And there she was again, trying to stick me with it.

I kicked her right in the ear.

But the doctor was up again and sitting on my chest, and the nurse was coming at me with the hypo again and—

‘Aaagh!’ screamed Driver Diver. ‘The Horseman is upon us. The Seventh Seal is open. The beast riseth up from the bottomless pit. It is Armageddon. We’re all gonna die. I’m swearing off drugs in the future.’

And the van overturned.

And me and the driver, the doctor and nurse went around and

around and around. And of course it all seemed to happen in slow motion, just like it would in a film.

The rear doors burst open and into the sunlight myself and the doctor, the nurse, and the trolley (or gurney or it-is-too-hard-to-come-up-with-any-more-trolley-jokes-now) spewed forth in a great churning mass of much chaos.

And yes, yes, I saw it. I know that I did: Mr Hugo Rune, riding on the back of a centaur.

All in slow motion.

Just like in a film.

And then fade out.

And cut.

And print.

And fade up.

And—

‘I told you that Danbury’s talks were always a riot,’ said Mr Rune, ‘but I do think he surpassed himself this time.’

I was alive! I felt at myself.

‘Please don’t feel at yourself in my presence,’ said Mr Rune. ‘I hope Danbury’s habits aren’t rubbing off on you.’

‘The centaur,’ I managed to utter. ‘And, oh, we are back in our rooms.’

‘An exciting night for both of us, wasn’t it? I thoroughly enjoyed the chase, reminded me of the time I rode with the Light Brigade at Sebastopol.’ Mr Rune offered me alcohol. I took him up on the offer.

‘A centaur,’ I managed to utter once again.

‘So you said. My hat, if I wore one – which I do upon certain occasions, although not state ones, as the Runes by Royal charter are granted the right to remain hatless in the presence of royalty – my hat, as I said, if I wore one, would be off to Mister Collins at this moment. You don’t see a centaur every day of the week. This is the first that I have seen for more than three hundred years. It is coming together, young Rizla. We are upon the cusp here. Time, it seems, is presently in a malleable state.’

‘I am confused,’ I said to Mr Rune. ‘I am

very

confused.’

‘You must learn to expect the unexpected, young Rizla. We have

added one more piece to the puzzle. One more badge sits upon your breast. Each episode brings us closer to our goal – to whit, the recovery of the Chronovision before Count Otto Black can lay his grimly nailed claws upon it. Much was learned by you last night, although you might not be aware of it. But it will all fit together for you in time. The manifestation of the centaur is only the beginning of what is to come. We can expect a lot more of such anomalous phenomena.’

‘Where is the centaur now?’ I asked.

‘It depends on exactly what you mean by “now”.’

‘I know

exactly

what

I

mean by “now”,’ I said.

‘Then it is no longer in

this

now. It is back in its own time, which although being the same “now” as this, is profoundly different, whilst being exactly the same. Did you not pay any attention at all to Danbury’s lecture? I personally found it most instructive. As well as being a riot.’

‘That doctor,’ I said, with terrible recollection, ‘he harvests the homeless for spare parts. We must do something about this. We must go to the police.’

‘You think they might believe you?’

‘Why would they not?’

Mr Rune shrugged. ‘They might,’ said he. ‘In fact, I feel certain that they would, for it is the police who scoop up the homeless from the streets and deliver them to the hospitals. The police might, quite naturally, ask you for some form of identification, of course. I wonder what might happen to you when you fail to provide it.’

‘But this is outrageous. Inhuman.’

‘Indeed,’ said Mr Rune, pouring for himself alone another drink. ‘And it will be dealt with. All such injustices will be dealt with.’

‘When?’ I asked.

‘In time,’ said Hugo Rune. ‘Everything will resolve itself in time.’

‘Can I have another drink?’ I asked.

‘It’s now

time

that you popped out to the offy,’ said Hugo Rune.

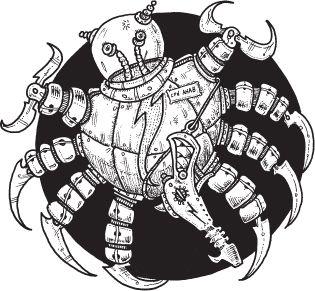

The Moulsecoomb Crab

PART I

I am sure that it must have been May when it happened. The Brighton Festival was on the go and many strange fellows were doing strange things in the town. There was a lot of ‘street theatre’, which seemed generally to consist of foolish people with whitely daubed faces climbing into cardboard boxes and fiddling about with fish. Things that I am told they did for Art.

Now, I confess that I have never been altogether comfortable with

Art. It comes in so many shapes and sizes and is more difficult to pin down than Iron Man Steve Logan, my favourite wrestler of the day. You knew where you were with the wrestling, of course. You were sitting in your armchair at four o’clock of a Saturday afternoon watching television with Kent Walton doing the commentary.

But Art, well, I was never comfortable with it.

I felt this irrational desire to smite the whitely daubed types, tear up their cardboard boxes and murder their mackerel, which brings me, albeit circuitously, to the next case that Mr Rune had set himself to solve: the Monstrous Mystery of the Moulsecoomb Crab.

Now, I had never set foot in Moulsecoomb. I had mooched all around and about the rest of Brighton in the hope of stirring something that would lead to the rediscovery of my identity, but the Moulsecoomb area remained a mystery.

I do not know what it is like these days. Perhaps it has ‘come up’ like so many other areas have. Perhaps the houses there now sell for millions. But back then in the swinging sixties, Moulsecoomb was a NO-GO AREA. And that was in capital letters.

It all went back to Victorian times, apparently, and the transportation of criminals to Australia. With the opium and slave trades having fallen off, worthy captains had put their vessels to use in the lucrative transportation of criminals to the lands of Down Under. The scheme – organised, I understand, by an early precursor of the NHS – was that the captains were paid for the one-way journey there only. They dropped off the criminals in Australia, then took on whatever cargoes they thought would prove profitable at home, and then returned.

The cargoes they acquired in Australia – platypus pelts, which were used extensively in the manufacture of theatrical costumery of the amphibious persuasion, and koala ears, which adorned many a fashionable Kensington dowager’s snuff-trumble – were profitable in their way, but it was the trip out that paid the bills. And Australia was a long way away. It took nearly a year to get there in those days, two if you took an accidental turn into the Gulf Stream and had to go via Canada. So the worthy sea captains shortened their journey times by dropping off the criminals in Brighton and returning to the port of London the pretty way, via Dublin’s fair city where the girls are so

pretty, with talk of favourable headwinds and excuses for their empty holds – that platypi and koalas had become extinct.

The criminals themselves, of course, knew better than to return to London and so set up a colony in the Moulsecoomb area, which was at that time all but impenetrable swamp, the haunt of the Sussex crocodile, the Hove hippopotamus, the Brighton bagpuss and any number of sundry other unlikeable beasties. And from there they engaged in piratical activities and freebooting.

The name ‘Moulsecoomb’ derives, of course, from the founder of the colony: the infamous pirate, brigand, plunderer and pigeon-fancier Black Jack Moulsecoomb.

Of evil memory.

Black Jack’s escapades remain to this very day the talk of the quayside taverns of Brighton. Wherever two grizzly salts meet together, the name of Black Jack is never far from their tattooed lips.

I must have always harboured a liking for pirates. Whether it was the cutlasses, or the flintlocks, or the Jolly Roger, or the drinking of rum, wenching of wenches, chewing of limes or the wearing of ostentatious earrings, I am unable (or perhaps unwilling) to say. But I like ’em.

Do not like Art, do like pirates.

It is simply a preference thing.

And I am sure I would have really liked that Black Jack.

It is said that when the weather held to fair and the barometer was rising, he and his scurvy crew would set sail from their secret inlet within the swamps of Moulsecoomb, cruise around the Brighton Marina and at precisely four o’clock on a Sunday afternoon (during the mixed-bathing season) pillage the Palace Pier.

Apparently, members of the aristocracy, lords and ladies and the like, who came to promenade upon the sundecks during that period did so in the hope of being pillaged by Black Jack and his pirate crew. Especially the ladies, for Black Jack was something of a Johnny Depp.

The upshot of all this, lest the reader think that I am losing the plot, is that Black Jack put it about all over the place, but nowhere more so than in the pirate enclave that he founded, with the result that it grew and expanded into the community that it became: the

den of iniquity known as Moulsecoomb, where policemen and right-thinking individuals feared to tread.

Back then, in the nineteen sixties, the barbed-wire entanglements were still up and Moulsecoomb had its own parliament and private army, the Moulsecoomb Militia, better armed and more greatly feared than any official British regiment. There were fewer pirates, of course. In fact, there was hardly one to be found, the last pillaging of the Palace Pier on record being in 1953, when Black Jack’s great grandson Grey Jim (for he was getting on in years) launched one final pillage as a tribute to James Dean who had died the previous week.

*

So I had never taken to walking alone around Moulsecoomb, and would certainly never have entered it at all if it had not been for Hugo Rune and his desire to visit the circus that was presently encamped upon the Palace lawns before our rooms at forty-nine Grand Parade: Count Otto Black’s Circus Fantastique.

‘We cannot go to

that!’

I told Mr Rune as he and I sipped champagne in The Mound and Merkin (for such was Fangio’s bar named upon this particular day). ‘Count Otto is your mortal enemy, or so you told me. And you never told me that he ran a circus.’

‘It comes to Brighton every year at this time,’ said Rune, quaffing champagne and chasing a tiny spaniel around an ashtray with a cocktail stick. ‘It’s part of the Festival.’

‘But he is the Moriarty to your Holmes – or so you told me.’

‘It is unnecessary for you to add the words “or so you told me” to each sentence. You may assume, and you would be correct, that I am aware of what I have told you.’

‘I suppose then that you will want

me

to acquire the tickets.’

‘No need,’ said Mr Rune. ‘Fangio here has two free tickets.’

‘Got them for putting up a poster,’ said Fangio, indicating the gaudy item that hung amongst the auto parts behind his bar. And drawing the bowl of complimentary peanuts beyond the reach of Mr Rune. ‘And I’m keeping them, too,’ he continued.