The Broken Land

Authors: W. Michael Gear

Tags: #Fiction, #Sagas, #Historical, #Native American & Aboriginal

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Nonfiction Introduction

T

welve summers after

T

he

D

awn

C

ountry …

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Thirty-six

Thirty-seven

Thirty-eight

Thirty-nine

Forty

Forty-one

Forty-two

Forty-three

Forty-four

Forty-five

Forty-six

Forty-seven

Forty-eight

Forty-nine

Fifty

Fifty-one

Fifty-two

Fifty-three

Fifty-four

Fifty-five

Fifty-six

Fifty-seven

Fifty-eight

Fifty-nine

Sixty

Sixty-one

Sixty-two

Sixty-three

Sixty-four

Sixty-five

Sixty-six

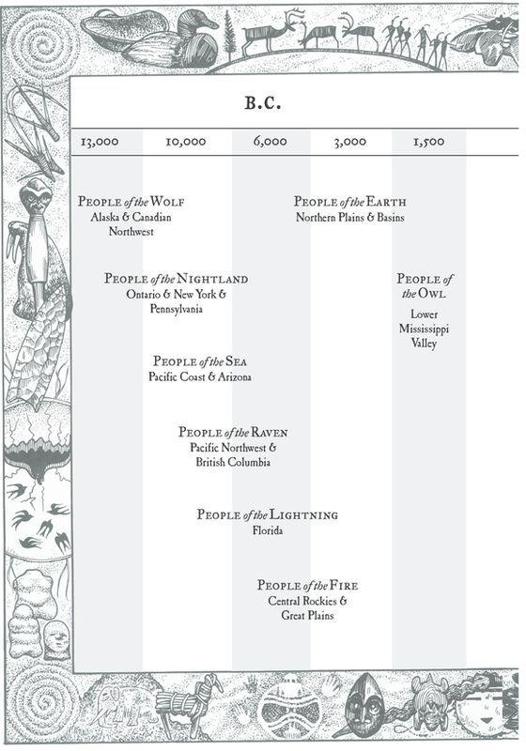

BY KATHLEEN O’NEAL GEAR AND W. MICHAEL GEAR FROM TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES

Glossary

Selected Bibliography

About the Authors

Copyright Page

To Linda Walters

English teacher at Tulare Union High School,

California, 1969–1972

She taught an amazing course called “Supernatural Literature,” where her students studied the works of writers like H. P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe. I well remember the outcry it caused in our small community, especially the charges that she was teaching Satanism. Despite pressure to stop, Mrs. Walters had the courage to stand up and continue teaching her students that classic body of literature. I know it wasn’t easy.

Thank you, Mrs. Walters. You will never know how much that class meant to me.

Your student,

Kathleen O’Neal Gear

T

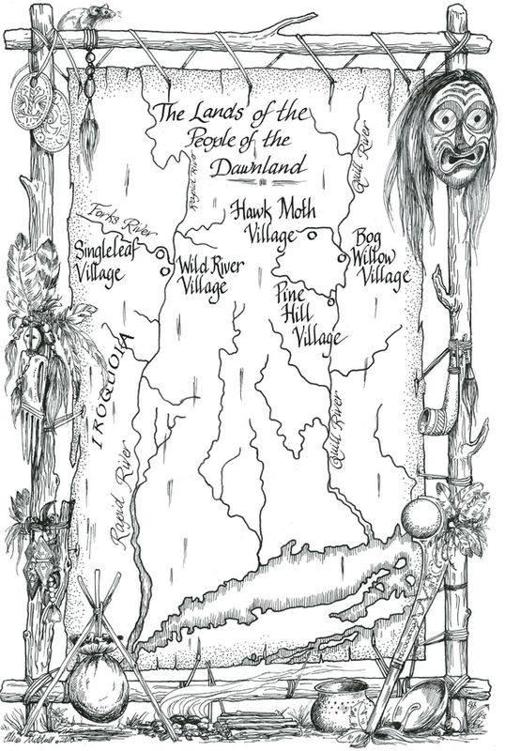

he Iroquoian story of the Peacemaker is one of North America’s most beautiful epics. There are literally hundreds of recorded versions, often contradictory, and many more versions that are kept alive only by Haudenosaunee

hegeota,

storytellers. These oral historians are the Keepers of the sacred stories. Despite sometimes profound differences, most of the Keepings share two elements: the story opens in a ferocious landscape of war, and three people are struggling to end it: Jigonsaseh, Dekanawida, and Hiyawento. For more information on the grisly nature of the warfare, please see the introduction to

People of the Longhouse.

Let’s talk about “Keepings.” What is a Keeping? Keeping takes many forms and is a sacred obligation.

Women were the Keepers of the Three Sisters: corn, beans, and squash. They were responsible for the agricultural fields, planting, tending, harvesting, and preserving the crops. As part of their Keeping obligations, women controlled food and its distribution. They also decided when to make war and when to make peace. Often this duty included fighting and leading warriors into battle.

As a fascinating example, in 1687 the French monarchy decided it would steal Seneca lands. King Louis XIV assigned one of his most decorated war heroes, the Marquis de Denonville, to lead the offensive. The marquis believed the best way to accomplish the task was to destroy Seneca government at the roots. He used a standard European military strategy that had proven very effective in dealing with the wild tribes of Ireland and Scotland; he invited the Haudenosaunee leaders—the Grand Council and several clan mothers—to a peace conference, then took them prisoner and shipped them to France as slaves. Fortunately, he was so ignorant of the role of women in Iroquoian society that he unwittingly left the most powerful woman in the nation, the Jigonsaseh, untouched. She made him regret it, for she called up an army of men and women warriors so powerful they virtually destroyed the marquis’s forces, and chased the terrified survivors all the way back to Montreal, handing him the most ignominious rout of his life. In 1688, the marquis pleaded for peace and agreed to all of the Jigonsaseh’s demands, including dismantling the French fort at Niagara and returning the captives who had survived their brutal slavery (O’Callaghan, 1: 68–69. See also, Mann,

Iroquoian Women,

chapter 3).