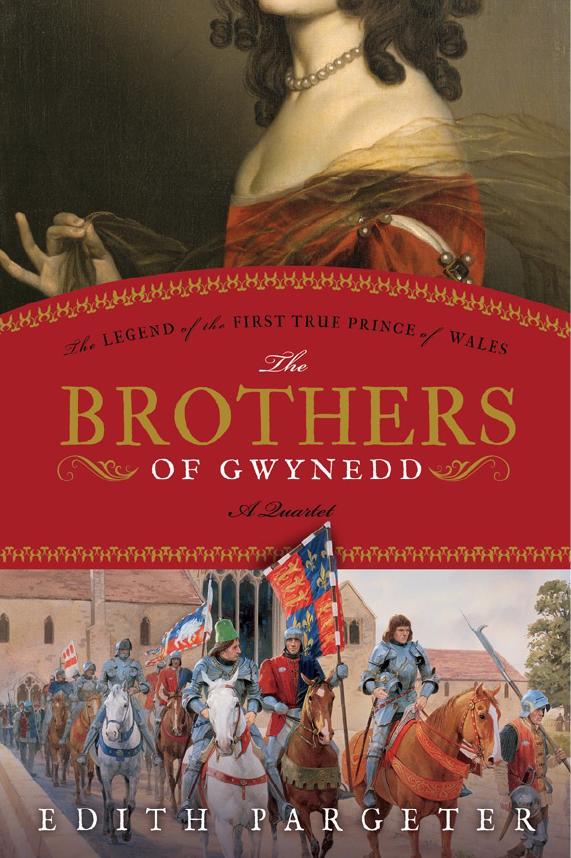

The Brothers of Gwynedd

Table of Contents

Copyright © 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1989, 2010 by Edith Pargeter

Cover and internal design © 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by The Book Designers

Cover and internal design © 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by The Book Designers

Cover images © National Trust Photo Library/Art Resource, NY; Graham Turner/ Osprey Publishing

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious and used fictitiously. Apart from well-known historical figures, any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

This novel was originally published in four volumes in hardback by Macmillan London Ltd in 1974, 1975, 1976, and 1977.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pargeter, Edith.

The brothers of Gwynedd : the legend of the first true prince of Wales / by Edith Pargeter.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, d. 1282—Fiction. 2. Gwynedd (Wales)—History—Fiction. 3. Wales—History—1063-1284—Fiction. I. Title. PR6031.A49B76 2010 823'.912—dc22

2009049913

SUNRISE IN THE WEST

The chronicle of the Lord Llewelyn, son of Griffith, son of Llewelyn, son of Iorwerth, lord of Gwynedd, the eagle of Snowdon, the shield of Eryri, first and only true Prince of Wales.

CHAPTER I

My name is Samson. I tell what I know, what I have seen with my own eyes and heard with my own ears. And if it should come to pass that I must tell also what I have not seen, that, too, shall be made plain, and how I came to know it so certainly that I tell it as though I had been present. And I say now that there is no man living has a better right to be my lord's chronicler, for there is none ever knew him better than I, and God He knows there is none, man or woman, ever loved him better.

Now the manner of my begetting was this:

My mother was a waiting-woman in the service of the Lady Senena, wife of the Lord Griffith, who was elder son to Llewelyn the Great, prince of Aberffraw and lord of Snowdon, the supreme chieftain of North Wales, and for all he never took the name, master of all Wales while he lived, and grandsire and namesake to my own lord, whose story I tell. The Lord Griffith was elder son, but with this disability, that he was born out of marriage. His mother was Welsh and noble, but she was not a wife, and this was the issue that cost Wales dear after his father's death. For in Wales a son is a son, to acknowledge him is to endow him with every right of establishment and inheritance, no less than among his brothers born in wedlock, but the English and the Normans think in another fashion, and have this word "bastard" which we do not know, as though it were shame to a child that he did not call a priest to attend those who engendered him before he saw the light. Howbeit, the great prince, Llewelyn, Welsh though he was and felt to the marrow of his bones, had England to contend with, and so did contend to good purpose all his life long, and knew that only by setting up a claim of absolute legitimacy, by whatever standard, could he hope to ensure his heir a quiet passage into possession of his right, and Wales a self-life secure from the enmity of England. Moreover, he loved his wife, who was King John's daughter, passing well, and her son, who was named David, clung most dearly of all things living about his father's heart, next only after his mother.

Yet it cannot be said that the great prince ever rejected or deprived his elder son, for he set him up in lands rich and broad enough, and made use of his talents both in war and diplomacy. Only he was absolute in reserving to a single heir the principality of Gwynedd, and that heir was the son acceptable and kin to the English king.

But the Lord Griffith being of a haughty and ungovernable spirit, for spite at being denied what he held to be his full right under Welsh law, plundered and abused even what he had, and twice the prince was moved by complaints of mismanagement and injustice to take from him what had been bestowed, and even to make the offender prisoner until he should give pledges of better usage. This did but embitter still further the great bitterness he felt rather towards his brother than his father, and the rivalry between those two was a burden and a threat to Gwynedd continually.

At the time of which I tell, which was Easter of the year of Our Lord twelve hundred and twenty-eight, the Lord Griffith was at liberty and in good favour, and spent the feast on his lands in Lleyn, at Nevin where his court then was. And there came as guests at this festival certain chiefs and lesser princes from other regions of Wales, Rhys Mechyll of Dynevor, and Cynan ap Hywel of Cardigan, and some others whose attachment to the prince and his authority was but slack and not far to be trusted. Moreover, they came in some strength, each with a company of officers and men-at-arms of his bodyguard, though whether in preparation for some planned and concerted action against the good order of Gywnedd, as was afterwards believed, or because they had no great trust in one another, will never be truly known. Thus they spent the Eastertide at Nevin, with much men's talk among the chiefs, in which the Lord Griffith took the lead.

At this time the Lord David had been acknowledged as sole heir to his father's princedom by King Henry of England, his uncle, and also by an assembly of the magnates of Wales; but some, though they raised no voice against, made murmur in private still that this was against the old practice and law of Wales, and spoke for Griffith's right. Therefore it was small wonder that Prince Llewelyn, whose eyes and ears were everywhere, took note of this assembly at Nevin, and at the right moment sent his high steward and his private guard to occupy the court and examine the acts and motives of all those there gathered. David he did not send, for he would have him held clean of whatever measure need be taken against his brother. There was bitterness enough already.

They came, and they took possession. Those chiefs were held to account, questioned closely, made to give hostages every one for his future loyalty, and so dispersed with their followings to their own lands. And until their departures, all their knights and men-at-arms were held close prisoner under lock and key, and the household saw no more of them. As for the Lord Griffith, he was summoned to his father at Aber, to answer for what seemed a dangerous conspiracy, and not being able to satisfy the prince's council, he was again committed to imprisonment in the Castle of Degannwy, where he remained fully six years.

In those few days at Easter, before the prince struck, the Lady Senena conceived her second son. And my mother, the least of her waiting-women, conceived me.

My mother came of a bardic line, was beautiful, and had a certain lightness of hand at needlework and the dressing of hair, but she was never quite as other women are. She was simple and trusting as a child, she spoke little, and then as a child; yet again not quite as a child, for sometimes she spoke prophecy. For awe of her strangeness men fought shy of her, in spite of her beauty, and she was still unmarried at eighteen. But the unknown officer whose eye fell upon her among the maids that Eastertide had not marriage in mind, and was not afraid of prophecy. She was young and fair, and did not resist him. She spoke of him afterwards with liking and some wonder, as of a strange visitant come to her in a dream. He took her in the rushes under the wall hangings in a corner of the hall. The next day the prince's guard rode in, and he was herded into the stables among the other prisoners until all were dismissed home. She never saw him again, never knew his name, or even whose man he was, and from what country. But he left her a ring by way of remembrance. A ring, and me.

That same night, for all I know that same moment, in the high chamber at Nevin, in the glow of vengeful hope and resolution, the Lord Griffith got his third child and second son upon the Lady Senena. Certain it is that we were born the same day. Nor was the lady more fortunate than her maid. For six years she saw no more of her husband, for he was held fast in the castle of Degannwy, over against Aberconway, and she here in Lleyn, on sufferance and under surveillance, kept his remaining lands as best she could, and waited her time.

At the beginning of the year of Our Lord, twelve hundred and twenty-nine, in January snows, in the deepest frost of a starry night at Griffith's maenol of Neigwl, we were born, my lord and I. The Lady Senena named her son Llewelyn, perhaps in a gesture of conciliation towards his grandsire, for beyond doubt it was in her interests to woo the prince, and she had more hope of winning some favour from him in the absence of her husband's fiery temper and haughty person. Certain it is that she did bring the child early to his grandfather's notice, and the prince took pleasure in him, and had him frequently about him as soon as the boy was of an age to ride and hunt. With children he was boisterous, kind and tolerant, and this namesake of his delighted him by showing, from the first, absolute trust and absolute fearlessness.

As for me, my mother named me after that good Welsh saint who left his hermitage at Severnside to travel oversea to France, to become archbishop of Dol, and the friend and confidant of kings. As I have been told, that befell some five hundred years ago, and more. Perhaps my mother hoped for some sign of his visiting holiness in me, his namesake, for I had great need of a blessing from God, having none from men. I think that at first, when she found her innocent was with child, the Lady Senena made some attempt to discover who had fathered me, that he might be given the opportunity to acknowledge me freely, according to custom, and provide me when grown with a kinship in which I should have a man's place assured. But my mother knew nothing of him but his warmth and the touch of his hands, not even the clear vision of a face, much less a name, for it was no better than deep twilight in the hall where they lay. And those who had visited, that Easter, were so many that it was hopeless to follow and question them all. And the ring, as I know, she never showed. For even to me she never showed it until I left her for the last time.

Other books

Grimm's Last Fairy Tale by Becky Lyn Rickman

The Finishing School by Gail Godwin

Stealing Through Time: On the Writings of Jack Finney by Jack Seabrook

Anything You Want by Geoff Herbach

Sword's Blessing by Kaitlin R. Branch

The Church of Mercy by Pope Francis

Jigsaw Pony by Jessie Haas

Who bombed the Hilton? by Rachel Landers

Grace by Elizabeth Nunez

Alarm Girl by Hannah Vincent