The Burgher and the Whore: Prostitution in Early Modern Amsterdam (20 page)

Read The Burgher and the Whore: Prostitution in Early Modern Amsterdam Online

Authors: Lotte van de Pol

comparable development, from participation in the fun on offer to aversion and avoidance. As we saw in Chapter

1

, this led to the rise of a stylish type of late eighteenth-century music house in which cus- tomers from the higher social strata were shielded as far as possible from the ugly realities of prostitution.

44

Two very different images of the Amsterdam Spin House have come down to us.The first is the official version, according to which the Spin House is categorized as one of the ‘houses of charity’, a benevolent in- stitution that brought honour to the city and was arguably a status sym- bol. A large number of prints were produced of the handsome exterior (Plate

2

). In most depictions of the workroom, artists convey an image of good and humane management: modestly dressed female prisoners sit quietly working, supervised by women, often at the moment when the Bible was read to them, as happened twice a week (Plate

8

).

There are far fewer depictions of the other image, the spectacle of unruly women, jeering visitors, and the crude verbal exchanges between the two. One example is a drawing of the workroom by Francoys Dancx (Plate

9

). Dancx was not only a painter, from

1654

onwards he was also an officer of the law, and he undoubtedly drew this scene from the life. We see an overcrowded, untidy room in which the tension is palpable; a supervisor has just boxed a prisoner’s ears with her mule.This drawing brings to life both the prisoners and the visitors watching and laughing at the women through the bars.There is one painting that deliberately embraces both aspects. It is a portrait of the regents of the Spin House, painted by Bartholomeus van der Helst in about

1650

.The regents are

two men and two women; in the Dutch

R

epublic women of the regent class could be found on the boards of public institutions that were an

extension of female responsibilities, such as orphanages, hospitals, and women’s prisons. They are serious, soberly clad burghers, conscious of the task for which they are responsible. Behind them, as if through a window, that task is shown: the supervision and disciplining of wayward women (Plate

10

). The painting depicts the contrast between the burgher, male or female, and the whore.

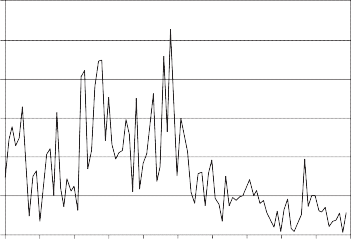

As mentioned in my Introduction, the Confession Books include the records of a total of

8

,

099

trials for prostitution between

2

February

1650

and

1

February

1751

. In the second half of the seventeenth cen- tury there were an average of

116

per year, in the first half of the eight- eenth an average of forty-six (Appendix

2

). The figures fluctuated greatly within this hundred year span, as Figure

4.1

demonstrates, with the peak years lying between

1672

and

1703

, reaching a high point of

264

in

1698

. After

1703

the annual total never again exceeded one hundred and after

1723

there were never more than fifty, with the sin- gle exception of

1737

.

This suggests that prosecutions for whoredom diminished markedly in the eighteenth century.The reality is more complicated.As time went on, first offences were increasingly dealt with outside the courtroom. If an arrest led to a court case, the woman was usually a repeat offender. Meanwhile, interrogations were becoming more prolonged and punish- ments more severe.The same held true for other crimes; the prosecution of prostitutes accounted for over

20

per cent of all court cases across the hundred years that are the main focus of this study. Only after

1750

did the number of prosecutions fall both relatively and absolutely. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, prostitution was largely tolerated.

The Confession Books give a good impression of prosecution policy, but they tell us rather less about the background to practical decisions

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

1650 1660 1670 1680 1690 1700 1710 1720 1730 1740 1750

Fig. 4.1.

Trials for prostitution in Amsterdam by year,

1650

–

1749.

taken day by day. It is clear that complaints from neighbours or close relatives and fights or other disturbances were likely to lead to prosecu- tions, yet these ultimately account for only a minority of cases.Years with many arrests are usually distinguished by raids, with campaigns specifically targeting, for example, the streetwalkers around Dam Square or the music houses on the Zeedijk and the Geldersekade.The motiva- tion for such campaigns is rarely apparent. Certain events, such as the outbreak of plague in

1663

–

4

and the various other crises in Amster- dam’s history, may have influenced both the prostitution trade and pros- ecution policy, but neither the available statistics nor the stories in the Confession Books indicate any such cause and effect. It is possible that raids on music houses and brothels in the final years of the seventeenth century were a reaction to the serious disorder of February

1696

known

as the Undertakers

R

iot, since the uproar and plunder were attributed to a ‘rabble of wenches and seafaring folk’ and the looting was said to

have been incited from within the whorehouses.

45

It is impossible to prove any causal connection. The influence of the

R

eformed Church, on the other hand, is well documented.

The municipal authorities and the Reformed Church

Although less than half the population of the Dutch

R

epublic belonged to the

R

eformed Church, it fulfilled the role of a state church and was the only denomination whose hierarchy had the power to influence

government policy. It certainly made use of its position. Within two months of the promulgation of the prostitution statute of

20

August

1580

, preachers and elders of the

R

eformed Church put in a formal complaint that too little was as yet being done to combat ‘improper brothel-keeping’.

46

From then on the consistory sent a delegation al- most annually to complain to the burgomasters about ‘sins that cry to

heaven’ such as gambling, dancing, celebrating the Catholic feast of Saint Nicholas, failure to observe Sunday rest, and, under the same heading, the existence of bawdy-houses and music houses.

In years when crises struck, there were calls for extraordinary meas- ures against, for example, drunkenness or the wearing of ‘seductive clothing’, and for the closing of theatres and brothels. In the Disaster Year

1672

, when the very survival of the

R

epublic was at stake, the consistory issued a petition beginning:‘Notwithstanding that the chas-

tising hand of God yet lies so heavily upon our dear fatherland . . . scan- dalous whoredom and cavorting and lasciviousness are again the fashion.’ The government is urged to take measures to suppress‘whore- houses and levity of all kinds’.The petition includes a detailed plan.

47

In the eighteenth century the consistory ceased its annual calls for steps to be taken, but in

1747

, with foreign troops at the borders of the

Dutch

R

epublic, it again sounded the alarm. A delegation handed the burgomasters a list of sixteen brothels against which action was needed,

‘so that God’s anger at such sins shall not be inflamed to even greater ferocity against us’. The burgomasters thanked the ‘brethren’ for their trouble,‘in the present circumstances especially, in which we see God’s rage so justly ignited by reason of our sins’.

48

People in authority, themselves

R

eformed Church members, were presumably also convinced of the connection between sin and crisis.

They were certainly aware that they would do well to take account of attitudes and opinions voiced from the pulpit. The relationship be- tween church and state was problematic, however, and the question of who had greater authority in which matters was a constant source of friction and conflict.The civil authorities usually came out on top in this kind of power struggle.The government often appeared to adjust policy according to the wishes of the church and it drafted its laws in the spirit of Calvinism, but practical implementation was at its own discretion.

49

Prostitution was no exception.The burgomasters generally received delegations courteously,‘acknowledged sins with regret’, and promised to take the matter up with the bailiff, with whom the churchmen were also advised to speak.The bailiff, responsible for implementing policy, had a good deal less patience. As an individual he belonged to the urban elite, so he was not happy to be lectured to by the delegates of the consistory (church council) who were members of a lower social group. Complaints seldom led to direct intervention and when they did it was often by a roundabout route, intended rather to frustrate than to support the efforts of the consistory. The bailiff would order raids immediately after the churchmen had decided to send another delegation to the burgomasters, hurrying to act before the complaints about whorehouses officially reached him—he had his sources within the council.When the delegation knocked at his door he was able to say, as he did in

1672

, that he needed no encouragement,‘since we are very vigilant against them, especially on high and holy days’. Indeed

‘the deputy bailiffs declared that such houses no longer exist’.

50

Pros- titution would then be left in peace again for a while.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century the reaction of the bailiff grew increasingly testy. In

1703

, in response to the claim that ‘the excesses of the music houses are now exorbitant as never before’, he ‘expressed amazement at this complaint, saying also that he did not know such excesses happened there, saying he had already dealt with them in person’.

51

After being taken to task several times in this way, the consistory, meeting in

1704

, decided that ‘as far as whorehouses and music houses are concerned, we shall henceforth no longer watch over them every year’.

52

The authorities nevertheless remained prepared to respond to spe- cific complaints. There were often problems with the Little Chapel (Sint Olofskapel) on the Zeedijk, famously a street of prostitution. In

1676

, at the request of the consistory, a sign hanging outside a brothel was removed. This ‘offensive signboard . . . like unto a whore-shop, intended to attract lecherous people’ had been hung directly opposite the chapel.

53

In

1700

the bailiff arrested a number of prostitutes and brothel-keepers after a complaint from the verger that during the afternoon sermon the previous Sunday there had been so much noise from the surrounding whorehouses that the ‘great commotion of thumping and slamming’ had hindered the minister in his preaching.

54

In dealing with members, the

R

eformed Church had its own inter- nal system of justice.Those who misbehaved could be called to account

by the consistory and might find themselves ‘censured’, which meant they were barred from the Lord’s Supper, had their membership sus- pended, and might ultimately face expulsion. Since even minor gov- ernmental posts were reserved for members of the

R

eformed Church and poor members were dependent on the church’s poor relief, count- less Amsterdammers had reason to take church norms and discipline seriously.

The

R

eformed Church saw itself as the community of God’s elect, so it was extremely important for its members’ reputations to be beyond

reproach.

55

Whores, bawds, and the keepers of music houses did not belong in such company. Indeed, since few were members, they are hardly ever encountered in its disciplinary cases.

56

One of the few ex- ceptions was addressed in crisis year

1747

. It concerned Maria van Waardendorp, a member of the

R

eformed Church and a notorious bawd. She was called to account ‘because many improprieties were

spoken of, to her detriment’. She was said to have led ‘a discreditable life’ in Dordrecht too. Summoned many times, she finally appeared before the consistory, half-heartedly defended herself, and finally ad- mitted that in

1740

she had been in charge of a music house on the Passeerdersgracht along with her husband, the equally notorious whoremaster Jan Plezier. Maria was placed under censure but simply left the church. In the same week the consistory sent the burgomasters a list of keepers of music houses and brothels with the urgent request that action be taken. Maria’s name appears among them.

57