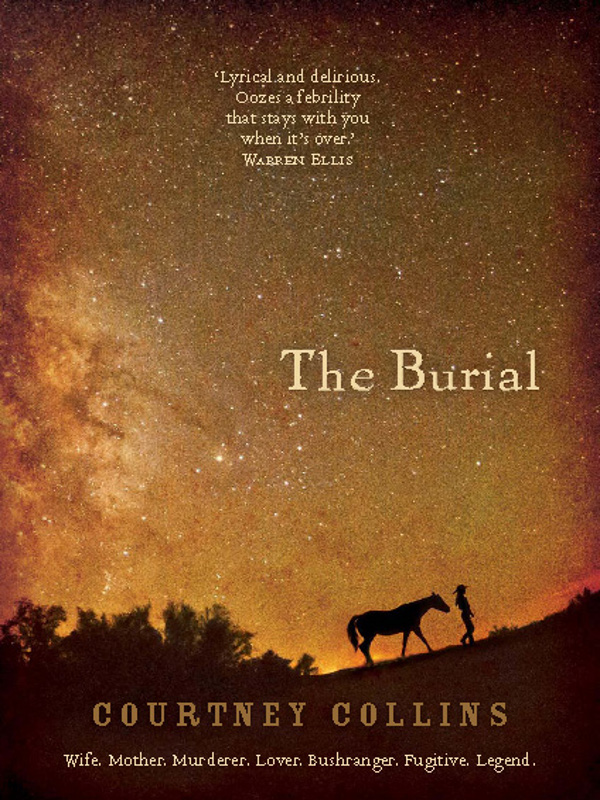

The Burial

The Burial

The Burial

COURTNEY COLLINS

First published in 2012

Copyright © Courtney Collins 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:Â Â [email protected]

Web:Â Â Â

www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 187 5

âTonight I Can Write', from

Twenty Thousand Love Poems and a Song of Despair

by Pablo Neruda, translated by WS Merwin, translation copyright © 1969 by WS Merwin. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Internal design by Sandy Cull, gogoGingko

Set in 12.5/17 pt Mrs Eaves OT CE by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed in Australia by McPherson's Printing Group

10Â Â 9Â Â 8Â Â 7Â Â 6Â Â 5Â Â 4Â Â 3Â Â 2Â Â 1

For my mother, with love

CONTENTS

âThe truth of the heavens is the stars

unyoked from their constellations

and traversing it like escaped horses.'

J

EAN

G

IRAUDOUX

, âSodom and Gomorrah'

âThis is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance.

My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her.'

P

ABLO

N

ERUDA

, âTonight I Can Write'

âHow could we ever keep love a-burning day after day if it wasn't

that we, and they, surrounded it with magic tricks . . .'

H

ARR

Y H

OUDINI

This is a work of fictionâinspired by art, music,

literature and the landscape, as much as the life and times of

Jessie Hickman herself.

WHO HASN'T HEARD of Harry Houdini? The Big Bamboozler. The Great Escapologist. The Loneliest Man in the World.

It is 1910. Harry Houdini, the World's Wonder, the Only and Original, is up to his armpits in mud. Intractable fingers of seagrass and kelp surge around him. With his eyes open, he can see movement and murky shadows.

He knows that above him twenty thousand peopleâstevedores, clerks, women in hatsâanticipate his death. They line Queens Bridge three deep. Past Flinders Street Station, all the way to Princes Bridge, they crane their necks and jostle for a view. Some have fallen over, tripped on hems and the clerk's pointed shoe, to see him, the World's Wonder, dive into the Yarra, handcuffed and wrapped in chains.

Slapped by seagrass, shrinking from shadows, Houdini brings his wrists to his mouth. With his teeth he pulls out a pin, one from each handcuff. The cuffs fall free and sink further down.

Houdini grabs at the weeds around him to anchor himself. They are loose and rootless, like slack rope. It is as if the river has no baseâjust layers and layers of sediment floating upon each other.

He tucks up his short legs and digs his knees into the sludge. His knee scrapes against some rock or reef and he reaches down to follow its seam. He runs his hand over a moss-covered thing, smooth, becoming fibrous, until his fingers catch in the familiar loops of a chain. The chain is thick and he follows its links until his hands hit up against a leg iron. And though he is running out of breath and he has yet to free himself from the locks around his neck, his hands seize around the thing within the leg iron. It breaks off. An ankle? A foot? Certainly not rock.

The thing is a thing of limbs.

Houdini gags. He takes in water. The taste is rotten. The thing of limbs is so eaten away by fish that Houdini's grasp has freed it. He is still clutching part of its brittle remains when the larger part of the body floats up and over him. It is the bluntest of shadows. Houdini beats into the sediment with his legs, stirring up a cloud of silt and other undiscovered things. He swims upwards at an angle, away from the cloud, away from the body, and reaches into his swimsuit for a key. He is just below the surface, veiled by murky water, when he finally frees himself from the locks around his neck. He breaks the surface and raises the locks above his head. Twenty thousand people cheer.

His wet curls conceal his face from the crowd as he turns in the water, searching for the body, the bloated mass. The river reveals nothing but ripples moving unevenly out to sea.

Houdini treads water, waiting for a boat. His chest aches. The rowers move too slowly, their oars striking and slicing the water in a rhythm that does not match the urgency he feels. He coughs and spits as they grow nearer. Finally, one of the rowers reaches down to him while the other balances the boat.

You swallow the river, Mr Houdini?

Houdini does not answer. He grips the man's arm and hauls himself up and into the boat.

Houdini is silent as the two men row him back to shore. His eyes continue to search the surface of the water but there is no sign of the bloated body and he cannot think of how to explain it or who to tell.

IF THE DIRT could speak, whose story would it tell? Would it favour the ones who have knelt upon it, whose fingers have split turning it over with their hands? Those who, in the evening, would collapse weeping and bleeding into it as if the dirt was their mother? Or would it favour those who seek to be far, far from it, like birds screeching tearless through the sky?

This must be the longing of the dirt, for the ones who are suspended in flight.

Down here I have come to know two things: birds fall down and dirt can wait. Eventually, teeth and skin and twists of bone will all be given up to it. And one day those who seek to be high up and far from it will find themselves planted like a gnarly root in its dark, tight soil. Just as I have.

This must be the lesson of the dirt.

Morning of my birth. My mother was digging. Soot-covered and bloody. If you could not see her, you would have surely smelt her in this dark. I was trussed to her in a torn-up sheet. Rain and wind scoured us from both sides, but she went on digging. Her heart was in my ear. I pushed my face into the fan of her ribs and tasted her. She tasted of rust and death.

In the wind, in the squall, I became an encumbrance. She set me on the ground beside her horse. Cold on my back and wet, I could see my breath breathe out. Beside me, her horse was sinking into the mud. I watched him with one eye as he tried to recover his hooves. I knew if he trod on me he would surely flatten my head like a plate.

Morning of my birth, there were no stars in the sky. My mother went on digging. A pile of dirt rose around her until it was just her arms, her shoulders, her hair, sweeping in and out of the dark while her horse coughed and whined above me.

When she finally arched herself out of the hole in the ground she looked like the wrecked figurehead of a ship's bow. Hopeful as I was, I thought we might take off again, although I knew there was no boat or raft to carry us, only Houdini, her spooked horse. And from where we had come, there was no returning.

She stood above me, her hair willowy strips, the rain as heavy as stones. Finally, she stooped to pick me up and I felt her hand beneath my back. She brought me to her chest, kissed my muddied head. Again I pushed my face into the bony hollow of her chest and breathed my mother in.