The Burning Shore (8 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

The sense of reprieve at BdU did not last long. Almost immediately, Dönitz realized that executing his new plan would be much more complex than he had thought. Godt and Hessler quickly calculated that only the long-range Type IX boats could reach the US East Coast, patrol for several weeks, and then return safely. The smaller Type VIIC boats could just barely reach Canadian waters off Newfoundland and Nova Scotia by proceeding at slow speed using one diesel engine to save fuel. BdU sent a message to Raeder’s office requesting the release of twelve IXB or IXC U-boats for what was being called Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat). The following day, Raeder’s staff

informed Dönitz that he could only have six, so he decided to increase the westbound force by adding seven (later expanded to twelve) Type VIIB and VIIC “medium” U-boats to patrol off northeastern Canada. If they could not join the hunt along the eastern seaboard of the United States, at least they could prowl the waters at the western end of the transatlantic convoy routes for any ships that managed to evade the Type IX boats.

During the next three weeks, U-boat flotilla commanders in France and Germany worked around the clock preparing the six Type IX boats assigned to Operation Drumbeat and twelve Type VII U-boats that would hunt in the Newfoundland–Nova Scotia area. Dönitz ordered the six Type IX boats to leave first. Beginning with U-502 and U-125 on December 18, the long-range boats set out across the Bay of Biscay. U-123 and U-130 departed five days later on December 23, with U-66 following on Christmas Day and the last IX boat, U-109, leaving port on December 27. The medium Type VII boats departed during a ten-day period between December 21 and 31. Included in that mix were five Type VII boats scheduled to leave Kiel on their initial combat patrols between December 24 and 30. One of them was Horst Degen’s U-701.

15

T

HE FOUR LOOKOUTS PERCHED ON THE

U-

BOAT

’

S CRAMPED

bridge scanned the horizon for the first sign of the enemy. High above a thin cloud layer, the waxing moon, three days from full, transformed the surface of the sea into bright liquid mercury. Wrapped in thick clothing against the subfreezing Arctic temperature, the men savored a rare calm.

On the bridge with the three other lookouts, Kapitänleutnant Horst Degen hunched over and spoke firmly into the voice tube connecting him with the radio room. “Send by short signal: ‘Have passed 60:50N. U-701.’” Down below in the small compartment, the two radiomen on watch began encrypting the message that would inform U-boat Force Headquarters in Lorient that as of midnight on New Year’s Eve 1941, the U-boat was nearly finished threading the hazardous, 110-nautical-mile-wide passage between the western coast of Norway and the Scottish Shetland Islands.

Degen and his crewmen were at battle stations. Standing lookout atop the bridge in addition to Degen were thirty-one-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Erwin Batzies, a naval reservist

serving as the second watch officer (2WO), twenty-eight-year-old

Obersteuermann

(Chief Quartermaster) Günter Kunert, the boat’s navigator, and an enlisted crewman. Even though not a commissioned officer, Kunert was an experienced seaman who had spent years in the German merchant marine. Degen had grown to respect his abilities as a navigator and later referred to him as “my best friend” on the boat. On the bridge, Degen and the other three kept their eyes peeled behind powerful Zeiss binoculars as each swept a ninety-degree arc. They had left the German port of Brunsbüttel three days before and were transiting an area of maximum danger. Several hours earlier, the boat had passed within thirty nautical miles of the Royal Navy Fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow, home to scores of British warships. Nor was that all. For the next five days, U-701 would steam on the surface within range of land-based British antisubmarine aircraft operating from Scotland, the Hebrides, and Northern Ireland. U-boat commanders such as Degen were very aware that nine U-boats crossing the North Sea and the east-west passage between Scotland and the Faroes had been lost thus far in the war.

1

Down below in the crowded, cramped U-boat, the other forty-two crewmen were also performing their battle station tasks, edging around the spare torpedoes, stacks of canned food, and other supplies as they quietly moved about. Despite the severe congestion, the young men were acclimated to their environment and well versed in their assignments after the months of combat drills in the Baltic.

In their nearly seven months together, Degen and his men had forged a tight bond. “Our lieutenant commander was a very correct and friendly officer despite his high command responsibility,” Gerhard Schwendel recalled of Degen many years later. “He was never authoritarian, but he always tried to maintain a good relationship with his team. He was thoroughly human.” Other crewmen would also describe Degen as a warm and caring man. But he was far from a pushover, as

Oberfunkmaat

(Radioman 2nd Class) Herbert Grotheer had found out four days earlier.

Kapitänleutnant Horst Degen (with white U-boat commander’s hat) musters the crew of U-701 on the U-boat’s main deck prior to getting underway on patrol. COURTESY OF HORST DEGEN.

When U-701 docked at Brunsbüttel for an overnight stopover before heading to sea on December 27, Degen had released two-thirds of the crew to go ashore for dinner. Grotheer and other sailors decided to visit the Hamburger Hof, a restaurant and pub popular with U-boat crewmen. The husband and wife proprietors ushered the sailors to a table and took their orders, then returned with a large guest book for them to sign. Grotheer turned the pages of the book and found the signatures of several of Germany’s highest U-boat aces, including Kapitänleutnant Joachim Schepke. A recipient of the

Ritterkreuz

(Knight’s Cross), Schepke was credited with sinking thirty-seven Allied merchant ships totaling 155,882 gross registered tons between September 1939 and his death the previous March. “U-100 expresses its gratitude for the lovely farewell evening at Hamburger Hof and looks forward to meet again during the next passage,” he had written. “For the time being, we have great plans, and want to fight out there and win. Heil Hitler—Schepke.”

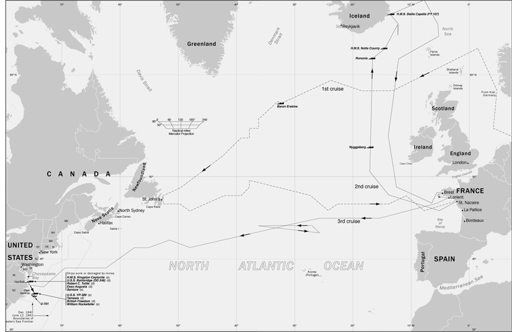

During its three war patrols, U-701 operated throughout the North Atlantic hunting for Allied merchant ships. ILLUSTRATION BY ROBERT E. PRATT.

As a trained radioman with a high security clearance, Grotheer had found the roster of U-boat visits to Brunsbüttel worrisome. He excused himself and returned to U-701 where he found Degen and told him of the potential security threat. Degen himself then went ashore and visited the Hamburger Hof, where the pub owners showed him the guest book and asked him to sign. He took a pen and signed his name but also blotted out the “U-701” that a crewman had added to the other U-701 crewmen’s signatures. Degen then wrote an urgent report about the guest book and had it transmitted to U-boat Force Headquarters by wireless from the U-boat tender tied up nearby. Degen later said he learned that “the entire establishment had been taken apart” by security officials.

At 0400 hours on December 31, Degen went below and ordered a slight course change from 332 to 320 degrees as U-701 began the northwest leg of its trip, which would take it between the northern tip of Scotland and the Faroes. After napping for several hours, he then sat at the small dining table with

several off-duty officers, including

Leutnant zur See

(Lieutenant j.g.) Bernfried Weinitschke. At 0745, the twenty-two-year-old Weinitschke, U-701’s first watch officer (1WO), stood up to put on his foul-weather gear and ascended the conning tower ladder with three enlisted men to stand the 0800–1200 lookout watch. Degen was still relaxing over coffee when a loud cry suddenly came down from the bridge: “Man overboard! The 1WO has fallen overboard!”

2

I

N EARLY

J

ANUARY

1942, 2

ND

L

IEUTENANT

H

ARRY

K

ANE

was not a happy man. While many U-boat men like Degen and his crew had already gone through basic training and were embarking on combat missions, the majority of American servicemen—land, sea, and air—were much less prepared for battle. The US armed forces as a whole, in fact, were ill equipped for the task before them—something that Harry Kane was finding out the hard way.

Kane found himself assigned to a medium bomber squadron stationed at a backwater base, flying what he called a “simply awful” aircraft and preparing to defend against a Japanese enemy that few pilots genuinely believed would reappear in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor.

The 396th Medium Bombardment Squadron was one of several hundred US Army Air Forces units (USAAF) created in early 1941 during the air service’s rapid expansion program. It was originally designated the 6th Medium Reconnaissance Squadron upon its activation on January 15 at March Army Airfield outside Riverside, California, but renamed the 396th Medium Bombardment Squadron several months later. For a long time it

wasn’t much of a squadron. Under USAAF procedures, a parent unit—in this case, the 38th Heavy Reconnaissance Squadron—provided an initial cadre of one commissioned officer and three dozen enlisted men. Its mission for the first five months of 1941 had been to perform “garrison duties” for the parent squadron: cleanup, mess hall, and other manual labor. Meanwhile, new personnel trickled in. In early May, the unit transferred from March Field to Davis-Monthan Army Airfield in Tucson, Arizona, with a complement of five officers and sixty-eight enlisted men. The 396th didn’t even get its first assigned aircraft until May 16, and it wasn’t much of an aircraft: a Boeing Stearman PT-17, practically identical to the PT-13 biplane that the airmen had flown in primary flight training. Several weeks later, USAAF officials turned up a second Stearman, and that summer, the steadily growing squadron—up to eleven officers and 218 enlisted men—turned in the trainers for two patrol bombers that, to most army pilots, were just as useless as the biplanes.

By 1941, army aviators considered the Douglas Aircraft B-18 Bolo bomber to be inadequate in every respect. It was under-powered, it flew too slowly, and it carried an inadequate bomb load of just 4,400 pounds. Its defensive armament consisted of only three .30-cal. machine guns. A variant of the Douglas DC-2 airliner first flown in 1935, the Bolo was fifty-seven feet long with an eighty-nine-foot wingspan and stood fifteen feet high. Its two Wright R-1820-53 radial engines gave the aircraft a maximum speed of only 216 miles per hour, a range of just 900 miles, and a service ceiling of 23,900 feet. In contrast, the four-engine Boeing B-17 could carry up to 8,000 pounds of ordnance at 287 miles per hour and had a range of 2,000 miles and a service ceiling of 35,600 feet. Compared with the Bolo’s three .30-cal.

machine guns, the Flying Fortress bristled with thirteen .50-cal. machine guns for defense against enemy fighters.

The day after Pearl Harbor, the 396th had transferred from Tucson to Muroc Bombing and Gunnery Range (today Edwards Air Force Base) in the Southern California desert, more than seventy miles inland from the coast. Then, on January 8, officials at Fourth Air Force Headquarters at March Field transferred the squadron to Sacramento Municipal Airport. The officers and enlisted men camped out in tents at the Sacramento Junior College stadium grounds. There, Kane was assigned as a junior copilot in the B-18 Bolo. Kane would later remember,

We were known as the second line of defense. Every morning about three o’clock . . . pitch black dark, we, the crew, from the copilot on back through all the enlisted personnel, would have to be in the B-18’s, have them cranked up, warmed up, ready to go. Of course, the older pilots could all stay in the operations room, keep warm, and all that business; but we had to stay in the airplane and keep the engines going and so forth. They would keep us out there usually with the engines running until daylight, and then they’d cut them off, and that was the end of that.