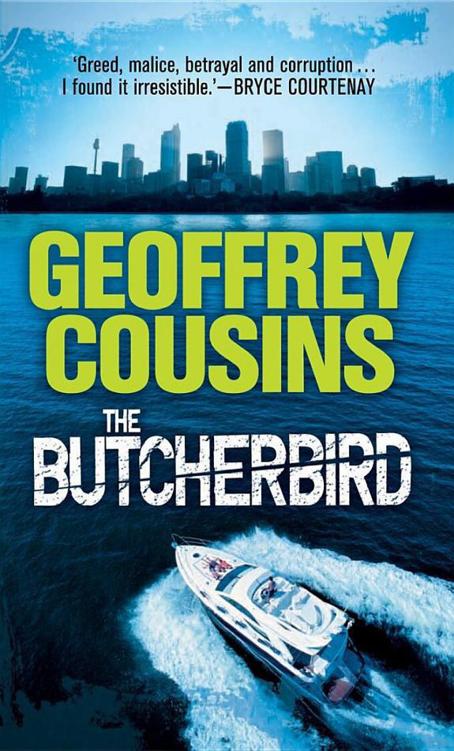

The Butcherbird

Authors: Geoffrey Cousins

| The Butcherbird |

| Geoffrey Cousins |

| (2009) |

Set in the boardrooms, yachts, and waterfront mansions of Australia's most decadent city, this boisterous thriller investigates corruption and excess in the corporate world. Jack Beaumont, architect turned property developer, is as surprised as the next person when he is approached by insurance tycoon Mac Biddulph to become the new CEO of HOA, the largest home-insurer in Australia. Seduced by power, Jack soon finds that beneath the glamorous facade of the business elite lies a convoluted network of corruption. Out of his depth and pursued by piranhas in a fish tank full of money, Jack must unravel the elusive threads or become ensnared himself. A darkly comic, suspense-filled tale of intrigue, this thriller poses moral dilemmas relevant to corporate sharks of today's business world--and to those left in their wake.

GEOFFREY COUSINS is one of Australia’s best known business and community leaders. His corporate life includes periods as CEO at George Patterson and Optus, in addition to positions on ten public company boards ranging from PBL to Telstra. He was the founding chairman of the Starlight Foundation and the Museum of Contemporary Art among many other community involvements. The Butcherbird is his first novel.

First published in 2007 This edition published in 2009

Copyright Š Geoffrey Cousins 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Cousins, Geoffrey.

The butcherbird.

ISBN 978 1 74175 601 2.

1. Entrepreneurs—New South Wales—Sydney—Fiction.

I. Title.

A823.4

Typeset in 10.35/12.68 pt Minion Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

109 8765 4321

To Darleen

This page intentionally left blank

The two Rolls-Royce engines buried in the bowels of the Honey Bear fired up with a deep-throated roar as the tangerine light of a late autumn sunset washed the castles lining the shores of Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Inside these exquisitely coordinated temples of taste—in the art deco style, or the Gothic style, or the French fifties style, or the French provincial style, or the God knows what style, and even in one, for reasons that none of the other owners could possibly fathom, an attempt at an ‘Australian’ style, which included such items as a dining table that had once served in a shearers’ mess together with a variety of farm implements scattered about the room, none of which were in fact Australian—women were shedding little tennis dresses in order to bathe before dining in some bistro that refused to take bookings, or explaining to friends on their B&O walkarounds why Charles was a wimp in every sense of the word, or rubbing their recently waxed thighs with special rose cream made in Portugal and only sold in one shop with no name, or screaming at their husbands who had arrived home early, for no reason, with no presents, no plans for dinner and a paunch that, in the dim light of dusk, looked even more prominent than it had that morning.

On the Honey Bear, all was soft, golden, sweet as treacle in a crystal jar. Indeed, Macquarie James Biddulph, master and commander of all he surveyed—one hundred and eighty-three feet of throbbing Huon pine and celery-top pine and swamp mahogany, all staterooms lined in suede leather tanned from the hides of his own cattle, from the vast properties in the Kimberley where they measured them in millions of acres—Mac as he was known to friends, and Big Mac to the press and to those who would like to be friends but had no chance of stepping across the great social gangway onto the sacred decks of the Honey Bear, Mac held a glass of Cristal of another origin in his prize-fighter’s mitt as he gazed benignly, patronisingly, at the gaggle of guests being piped aboard. Of course, there was no piper, although the thought had floated through the Big Mac mind more than once before it was dismissed as a touch ostentatious, though only a touch. But there was a bevy of immaculately turned-out crew members of both sexes in pristine white shirts and tailored navy shorts—tight-fitting shorts so the tight arses of the girls and the bulging quadriceps of the young men could welcome the guests with promises and glasses of vintage, and fresh peach juice for those who just drank peach.

Mac stood on the bridge, three decks and thirty feet above this assemblage of bronzed concupiscence, legs apart as if bracing against a rolling sea. The massive torso was bare and golden (waxed in the privacy of his own castle by a maiden who received a great deal more than the standard waxing fee and who would never reveal the secrets of the Big Mac chest). The Big Mac loins were covered only by a triangle of leopard-print silk, and the snowshoe feet with kangaroo skin sandals.

Although Mac was only five feet eight inches in his sandals, the width across his shoulders appeared approximately equal to his height, producing the impression of a solid block of squareness where the sum equalled more than the parts—although ‘there’s nothing wrong with the parts’, as Mac was fond of saying. As if in confirmation, he glanced briefly at the apex of the leopard print, the bulge, the discrete (although not so discreet) mound straining at the Italian silk. Yes, it was there all right. You might not be able to see the Mac prick but you certainly knew it was there. It was a presence at the party and all the guests would sense it when they fronted up to pay homage—all packaged up like department-store boxes in their navy blazers and chinos and neat white shirts and tiny diamond bracelets, while he, Big Mac, a name they would never dare to speak on the Honey Bear, stood before them so full of juice, so full of torque, they would have to look away.

He gazed at them now as they came aboard. Talk about a motley crew. What was motley anyway? Whatever it was, this lot was it. God knows why he asked some of them. Because they were all usable in one way or another, he supposed. Look at that old ponce, Laurence Treadmore, tiptoeing across the gangway as if he was avoiding a dog turd—Sir Laurence for Christ’s sake. Picked up his knighthood before Australia abandoned all that crap for those little lapel buttons everyone clamoured for. The dried-up old prune was even wearing a tie. A tie, on the Honey Bear? Never before seen, not even when Prince Charles sailed aboard wearing some sort of cravat. But tie or not, Sir Laurence was the chairman of his board and useful, full of useful qualities. Namely that he loved money and would rationalise almost anything to get it. And a fair chunk of his money, a handsome pile of millions (stashed somewhere, probably up his benighted arse since he never seemed to use any of it, to enjoy any of it), had been provided, directly or very indirectly, by Mac—or rather, if you wanted to be pedantic about it, by the shareholders of Mac’s company.

And who was that behind the neat, prissy figure of Sir Laurence? Ah yes, one of the pigeons for the weekend: Jack Beaumont, the property developer. Well he at least seemed likely to enjoy the pleasures on offer. Good-looking fellow, though lacking the power, the charisma, the bulging triangle of a Big Mac, of course. He was only a baby pigeon in the great scheme of things, but nevertheless he had something to offer. And offer it he certainly would by the end of a weekend under the spell, the delicious warm embrace of the Honey Bear and all she had to offer. And here came some of that sweet, sweet candy.

God he loved to watch Bonny skip onto the boat. She seemed to skip, literally, she was so supple and full of life and youth and crushed fruit and mung beans or whatever the hell she ate. She was always stretching or bending or clenching her tight little buttocks to make them tighter still, though they couldn’t be any firmer or rounder or more perfect, as he knew only too well. There wasn’t a hair anywhere on her body except on her beautiful head, not one hair. He knew, he ought to know, since he paid for all those Brazilian jobs and facial mud cleansers and polishing and sluicing and colonic irrigation and everything else that went into keeping that perfect, smooth, taut body exactly the way he wanted it. And that was the point. He wanted it. Why not? Wouldn’t any sixty-four-year-old man want a body like that sliding and rubbing and slipping and pulsing its way across his sculpted loins? It was a mystery to Mac why all men who could afford it didn’t have a Bonny tucked away somewhere. Sure you had a wife, and kids if you must, but you had a Bonny to keep the juices running. She was his personal trainer in her official capacity, and a fine result she delivered. Look at him. How many men of his age had the biceps, the latissimus dorsi, the quadriceps, the sixpack—well maybe not quite the sixpack, but all the rest, all firm and hard and ready. The odd barnacle here and there, it was true. That’s what Bonny called them, his ‘barnacles’, but that was an honest enough thing on a ship that had sailed more than a few miles. He was still seaworthy, that was the point. Seaworthy, shipshape, ready to voyage. And Bonny helped to keep the engines turning over.

Look at her little friends coming on board. They were all sanded and polished and varnished. Smooth, sweet, happy, grateful little honey pots. He loved every one of them. Which wasn’t to say he didn’t still love Edith. In his own way. But she was always asking him that: ‘You still love me, Mac, don’t you?’ And he always gave the same answer: ‘I’m here, aren’t I?’

As for the contrast between these beautifully wrapped little bonbons and the amorphous lump of old political horseflesh following them, well it was almost enough to turn the stomach. Why didn’t Harold Wilde do something about himself? Although what that might be Mac wasn’t sure. There was no way any of Bonny’s medicine ball throwing or shadow-boxing exercises (Mac loved to punch at her) or squats or anything could wear away the rolls of fat that were flopping around under that tent of a shirt. There must be a couple of kilos in the neck folds alone. Disgusting. The huge behind just sat itself on a soft Senate seat and dozed until it was lunchtime or dinner time or some meal time no one had ever heard of, and now it was waddling its way onto his boat behind his collection of sweetmeats, defiling the soft evening air, a great heaving mass of visual pollution. But useful, potentially useful. So feed him up, let him leer and sip and sup. One day, some day soon, it would pay back in spades. Mac gave him a cheery shout as he lurched his way aboard and the great bloated jellyfish almost slipped over as he looked up.

He would have slipped over if it hadn’t been for the steadying hand from behind that grabbed at some protuberance poking out from the tent. There was Shane O’Connell, where he always was, lurking just behind someone, ready to pick up any crumbs that fell from a corporate table or grease some grateful politician’s way into a sinecure. He was another member of Mac’s board, the company that was the great provider, the tree of plenty, the goose of goodness, the cream jar for all these sticky-fingered players and hangers-on and pigeons; the company he, Mac, Big Mac, had created, sired—yes, sired like a great stallion and then given birth to like a … well anyway, sired like a great stallion. By sheer force of personality and guts he’d wrenched it into the world, and now it was the largest home-insurer in Australia, a name everyone knew, HOA, Homes of Australia—the name he’d given it, just as he’d given it life and form and air.

But you had to watch people like Shane O’Connell. They were not always unquestioning in their allegiance to Mac, to HOA. They failed to understand that the two were indivisible, that HOA was nothing without Mac and that Mac was—he jerked back from that thought as if slapped with a wet fish. Sure, all his vast, complex, interlocking, tangled fishnet of private companies and Swiss bank accounts and hedge fund investments and trust funds and God knew what else (well he hoped God knew because Mac could never understand it all), sure this stuck-spaghetti mix all lived on the sauce of HOA, but there was no reason ever to assume that sauce would cease to flow. Maybe now and again Mac woke in the night, in the room he’d moved to across the hall from Edith, or in the apartment, with Bonny breathing softly, evenly beside him, the magnolia scent of her breath mingling with the musk of her mounds and clefts. Yes, he woke sometimes despite his oft-repeated boast, ‘I always sleep like a baby’. (Babies woke, didn’t they?) But not often. And not for long. If there was a problem, and lately there’d been one or two icebergs in the water, he attacked ferociously and sank them, or whatever you did to icebergs.