The Cactus Eaters (22 page)

Authors: Dan White

One night we were camped out on the bare rocks on the shores of Smedberg Lake, a bowl of black gloss deep in the interior of Yosemite National Park. The words just blurted themselves out of me. We’d hiked all the way from Los Angeles County—and I didn’t want to stop.

“I don’t think it’s right that I have to get off the trail with you,” I said.

“What?”

“You heard me. I really don’t think I should have to get off the trail because of

your

book.”

The fight was on. We spoke in fusillades, words blasting into one another. To the bears and squirrels listening in on us, our fight must have sounded like one sustained sentence with no punctuation. We circled each other, with me baring my incisors at my girlfriend and jumping up and down. Both of us were convinced that the other party was obstinate, out-to-lunch, a mental homunculus devoid of fair play, reason, and rationality.

“I don’t want to get off the trail

,” I shouted.

“You agreed to get off the trail,”

she shrieked. Clearly, reason was not working for us.

Compromise was not in the air. This was one of those fights that would have to be won by decibels alone. If she screamed at me, I’d just have to scream louder. There I stood, making sounds like lions and foghorns as I stood above Smedberg Lake, a water body I could not even begin to describe now because I paid so little attention to it, lest its natural beauty distract me from my yelling. After a while, she responded by getting quieter while I got louder.

“You knew I had to do this, Dan,” she said.

“No, I did not. This is your book. You did not tell me this. You’re ruining my dream for me. You’re derailing my dream.”

“So this is

your

dream now? Know what, Dan? You look crazy right now. You’ve been shouting at me over a stupid hike, and yes, you look insane, and you’re freaking me out. You’re scaring me and I’m

alone

out here. I don’t have anywhere to go and you are

fucking screaming at me over a hike.

I just need you to stop it now. I just want you to get a hold of yourself or take a walk or go somewhere, but just

stop screaming at me.

”

I stopped myself somehow, and the night got quiet. I heard nothing at all but the shameful ringing in my ears from my shouting. I walked away from the tent, just to get away from her, get away from us, and more than that, get away from myself. I stumbled around shore without a flashlight and watched the moon on the lake, bubbles on the surface, and something, a bug maybe, sending ripples through the moon’s reflection. The water murmured on the lake’s edges. When I returned to the tent, my voice had been stripped. I could not even bring myself to say good night. We fell asleep, but not in each other’s arms. My dreams erased the memories of the fight, but just momentarily; the blotted-out memories of the night returned as soon as I woke with a scratching throat under the white sky over Smedberg Lake.

We got off the trail two days later, near Lake Tahoe.

A

llison was angry and silent, but she took the time to bathe me as we stood in the shade near the highway shoulder. She swabbed a washcloth over my face and neck. I don’t know why she did this, and I didn’t understand the look of maternal concentration on her face. The washcloth smelled of Stilton cheese, cat farts, and moldy strawberries. In fact, Allison had dubbed the cloth “the odoriferous skankrag.” By now, I’d grown accustomed to our odors. They made me feel authentic. Our scents were like period costumes that gave us something in common with nineteenth-century pioneers. Some of those emigrants bathed only once a month. They must have smelled like us. I was squeamish when I started out on this trail. Now I was getting accustomed to filth. According to

Backpacker

magazine,

*

Pacific Crest Trail hikers are among the most foul-smelling things on this planet. Their “suffocating reek” comes

not from sweat itself “but from the bacteria that feed on the amino acids, fats, and oils found in human perspiration. The bacteria emit a putrid blend of chemical compounds including ammonia and methylbutanoic acid that cling to the clothes and body—and multiply with each passing day. Opening the car windows will only help so much, but at least it spreads the misery. Depending on wind conditions, someone could pick up this hiker’s aroma from 100 feet away.”

The fact that we had to scrub the stench away just to “fit in” outside the trail, just to hitch a ride to a supply town, filled me with disdain. And so I winced and made faces as she washed me, daubing my chin, anointing my forehead with redistributed sweat and dirt. Every time I swallowed hard, I felt the ache in my throat. My sore throat reminded me that I’d lost control forty-eight hours ago at the lake. I’d behaved boorishly. I couldn’t even begin to apologize for all my gnashing and howling. And yet it was all I could do to keep my mouth shut during the cat bath.

We were close to the northern tip of the four-hundred-mile-long Sierra Nevada range, a short drive from the Nevada border, a few miles to the east. This was where the emigrants crossed after rolling westward from Kansas, Missouri, and Wyoming in the 1840s. The pioneers, like the Lois and Clark Expedition, were only trying to find something better. They dared liberate themselves from the banality of convention. And here we were, leaving the woods, but not by choice, heading straight for the banality we’d tried to escape. A young couple stopped to give us a ride that day. They were kind, and engaged us in small talk, but I could not help but notice when they rolled the car windows way down to release our stench.

South Lake Tahoe, on the California-Nevada border, was ten minutes by car from the trailhead, but it might as well have been on Neptune. We arrived at a long reach of strip malls, pizza parlors, KFCs, motels, and bars with the green foothills bubbling up just behind them, as if to mock them, and then the big-boned

mountains, and there, in the middle of all this, the lake itself, sitting there like an afterthought, 1,643-feet deep, nestled in a valley between the Sierra Nevada and Carson ranges. Burned out, wanting fast food, we decided to spend a half-day in Tahoe before taking the bus to Sacramento, but we were at a loss, wandering the town in a haze, past a late-night carnival Tilt-O-Whirl, and a real estate office, with a rumpled man working the phones, his tie draped across his left shoulder. It seemed inconceivable that the world could contain the rumpled man and the trail, and yet we were less than ten miles from the trailhead.

We bummed around. I passed a shop selling T-shirts with almost incomprehensible sexual puns on all the shirts. One showed a cartoon of a leering man forming a hole with his right-hand thumb and pointer finger, and sticking his left-hand pointer finger into the hole. The caption read, “I don’t know any women who cry, but I know a few who sure like to bawl.” How stupid is that? “The pioneers didn’t have to deal with all this materialistic crap,” I thought to myself. This world is not real. Only the mountains above this town are real. With misanthropic relish, I imagined termites nibbling down the faux-Alpine motels, and casinos tumbling in the lake. I’d been to Tahoe once before, with my mother and father. They took me to see Tom Jones at Caesar’s Palace. I remember the wind machine, and Tom Jones wiggling through a fake fog that was really just liquid nitrogen, and the vixen-in-estrus yelps from the women, who were probably just making fun of him. Now I was walking in Caesar’s Palace once again, this time with Allison, past a false waterfall and plaster frescoes, electric pyramids, and a Cleopatra impersonator who looked and sounded as if her ancestral homeland were Sheboygan, Wisconsin. When we’d had our fill of casinos, card sharps, and the all-you-can-eat stroganoff buffet, we jumped on the Greyhound bus. It was a two-hour ride in black darkness on I-80 at sixty-five miles an hour. I did not bother looking out the window. Why look out

at all that inauthenticity? Allison saw me looking glum and she nudged my shoulder. “Next stop, Excremento,” she said, and we both laughed.

I was feeling glum, in withdrawal from the trail, when we holed up at her aunt’s house. I paced the hall, gnashed my teeth, and tried to give Allison space, because she was under deadline pressure and I didn’t want to upset her anymore. To give her a break, I wandered the deserted streets of a nearby town. While Allison faxed messages to her editors, I sat around at a diner drinking sour coffee and chewing

Exxon-Valdez

hash browns. Later, I stared for fifteen minutes at a closed-down movie theater with an existential message on the marquee:

COMING SOON TO A THEATER NEAR YOU

! How, I wondered, could a theater come to itself? At least Allison got her work done, while I was able to keep my hair-pulling to a minimum. But my feelings built within me, a surge of mute nostril agony that I could not control. With no other option, I vented my primal despair to my diary. The result was a passage that continues to amaze me with its primitive yet graceful display of incandescent rage. It ranks among the purest things I’ve ever written:

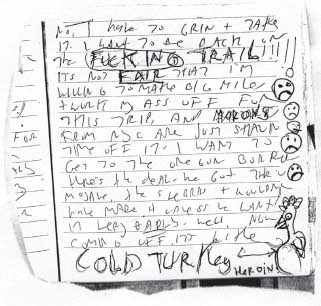

I want to be back on the fucking trail. It’s not fair that I’m willing to make the big miles and work my ass off for this trip and morons [

bastards

here has been crossed out, with

morons

written across it as a replacement] from NYC are just shavin’ time off it. I want to get to the Oregon border. Here’s the deal. We got thru the Mojave, the Sierras and wouldn’t have made it unless we want it very badly, well, now coming off it’s like cold turkey heroin!

I hid this blast of poetic fury from Allison. All told, we were off the trail for about a week. Thank God for Allison’s cousin Tom, who lived in a nearby town and gave us an unexpected gift before we returned to the trail: two Day-Glo orange vests

and baseball caps saying

LOIS AND CLARK EXPEDITION

with stick-on black letters. My hat said

CLARK

. If only the Gingerbread Man could see us now! It’s one thing to get a trail name. It’s another thing to accessorize. For a shining moment I felt famous, the vest and hats’ loud colors shouting our greatness and glory. But Tom warned us that the clothes would serve as more than fashion statements. Bear hunting season was almost upon us. He didn’t want some drunken hunter with a sporting rifle blowing us all to hell.

Actual Diary Entry

After taking a bus from Sacramento back to South Lake Tahoe and hitchhiking back to Echo Lake, we returned to the trail, wearing our bright orange outfits with pride. We were part of a team again as we passed into the Desolation Wilder

ness, hiking past Aloha Lake, a flooded valley with lodgepole pines protruding from the middle. The wind made the bare snags tremble. Once more I thought of the pioneers and what it must have been like to roll through a landscape that seemed to laugh at human ambitions and dreams. But we were beating that landscape now. After going this far on the trail, nothing seemed undoable. Near Blackwood Creek, we were in an expansive mood, feeling giddy and determined. We decided that someday we would open a bookstore together and name it for a literary suicide. We agreed, after much consideration, to call it Sylvia Plath’s Oven. There would be a sign out front saying,

EVERYBODY

,

STICK YOUR HEAD IN HERE

. There is something about a mountain setting that makes such ideas seem good at the time. As we entered the Granite Chief Wilderness, my calm, and hopes of success, returned in full. It was August 25. By my best calculations, we had two months to walk a thousand miles—and no more interruptions. As the trail reached a mountain crest, we looked above the clear-cut slopes of the Squaw Valley ski area and saw a pair of eagles launch themselves off a pine bough. They looked clumsy at first but found their momentum and rose up weightless.

The trail followed a rock spine on jumbled crags with granite spokes. Just north of where Allison and I were walking that day, an emigrant party steered their wagons across a treacherous pass. They were the first such group to cross the Sierra Nevada. The leader was a fellow I’d never heard of, named Elisha Stephens, forty years old and ugly as a possum. His neck was crooked and his beard was a tangled mess of tufts. You could hang your hat on his nose. In spite of his looks and lack of leadership experience, he’d been voted the captain of twenty-five men, eight women, nine girls and eight boys, all in eleven wagons that left from Council Bluffs, Iowa, in the spring of 1844. His destination was Sutter’s Fort, in New Helvetia, California. Why did he set off on this journey? It’s hard to say. A taciturn

man, Stephens left no diary behind. He must have had strong reasons to take a journey to the West when such ventures were considered insane or at least stupid. Maps of America stopped dead at a blank space from the Rockies to the one hundredth meridian, an expanse so empty there were no railroad tracks or roads, not even a telegraph wire.

What, then, was the appeal? Perhaps he wanted to get rich, but the gold rush was five years off. Maybe he craved free land or was as sick of his old life as we were when we ditched our jobs and left for the trail. As he headed west, Stephens suppressed a mutiny, drove footsore cattle through creeks, and felt the sun burn down on the misnamed Forty-Mile Desert, which was twice that long. After all that hardship, Stephens and his party entered the Sierra Nevada. They arrived at a granite ledge very close to where Allison and I were hiking that day. The ten-foot rocky barrier blocked the way. The Stephens party could have panicked or given up. Instead they emptied their wagons and hoisted each one up the ledge, using a rope pulley chained to the backs of their oxen. This emigrant party was resourceful as well as lucky; the group lost no members on its journey westward. In fact, it increased as it went along because of two babies born en route. Stephens and his crew opened up a mountain pass that became indispensable for thousands of other emigrants, including the forty-niners, not to mention the railroad and freeway that would both breach the pass, sending millions more people through the mountain notch.

I wonder if Stephens fantasized about fame and glory when he made it through this stretch. I, certainly, had such fantasies. Sometimes, at the end of a trail day, I pictured Allison and me finishing the trail and becoming highly paid motivational speakers, teaching self-esteem to addicts and fatties. But Stephens, if he had such notions, was in for a jolt. After his trek, he lived in obscurity in what is now Cupertino, California, and ended his days as a reclusive beekeeper and chicken farm

er in Kern County. In the late 1860s, after thousands of Chinese and Irish laborers finished laying out the Central Pacific Railway route across the mountain pass, no one thought to invite poor Stephens to the ribbon-cutting ceremony. He became the town grump, bitter and grumbling. One day, he had a stroke and ended up paralyzed in a local hospital. Soon after, he dropped dead. Gravediggers planted him in a potter’s field in Bakersfield, with no headstone. The cemetery lost his internment records. Silicon Valley landmarks perpetuate but misspell Stephens’s last name—among them, Stevens Creek Boulevard and Stevens Creek Auto Mall.

*

But when you drive on Interstate 80 from Reno to Sacramento, you will not see Stephens’s name on the signs along the pass he opened. Instead, the signs pay tribute to another group of emigrants who crossed the pass two years after Stephens rolled through. Their western journey would have little historical significance if not for some of the emigrants’ unprecedented barbarism and savagery.

The name of that group is the Donner Party.

On August 27, three days after we returned from our Tahoe interlude, we hiked on a rocky hump on the Sierra Nevada’s northern tip. The trail, a foot-wide strip, approached Tinker Ridge, a hatchet-shaped rock overlooking Donner Pass. Old Highway 40 was a short way downhill from us, so we were only slightly startled to see a family approach from nowhere, a man, woman, their young daughter, and two coiffed Afghan hounds. The dogs walked close enough for me to smell their rosy perfume and admire their bright ribbons. The girl gave us a hateful wince, perhaps because of our Day-Glo reflective outfits. Down we walked through fir and pine as we crossed the

flanks of Mount Judah, the crag the pioneers spied from Nevada to the east as they neared California. We dropped to the highway near Donner Summit, on a strip of black gravel under tall trees. Here, the south-to-north Pacific Crest Trail came within screaming distance of the Donner Party’s east-west route, though it is hard to pinpoint where the wagons crossed; earthmovers have widened the pass so much that the Donners might not even recognize it now. Standing near a

DONNER PASS

sign, Allison placed her right wrist in her mouth and chomped down hard enough to leave pink marks in her skin. I photographed this. Then we traded places, and I pretended to eat my left forearm. In the trail journal, I jotted the lyrics of a spontaneous song we sang there in honor of our arrival that day. It’s sung to the tune of “Yesterday” by the Beatles.