The Caine Mutiny (12 page)

CHAPTER 8

Captain de Vriess

Willie planned to sleep after lunch. He was longing for sleep with every cell of his body. But it was not to be. He and Harding were collared after coffee by the “vegetable with a face,” Ensign Carmody.

“Captain de Vriess says for me to take you two on a tour of the ship. Come along.”

He dragged them for three hours up and down ladders, and across teetering catwalks, and through narrow scuttles. They went from broiling engine spaces to icy clammy bilges. They splashed in water and slipped on grease and scratched themselves on metal projections. Willie saw everything through a reddish haze of fatigue. He retained only a confused memory of innumerable dark holes cluttered with junk or machines or beds, each hole with a novel odor imposed on the pervading smells of mildew, oil, paint, and hot metal. Carmody’s thoroughness was explained when he mentioned that he was an Annapolis man, class of ’43, the only regular officer aboard beside the captain and exec. He had narrow shoulders, pinched cheeks, small foxy eyes, and a tiny mustache. His conversation was spectacularly skimpy. “This is number-one fireroom,” he would say. “Any questions?” Harding seemed as tired as Willie. Neither of them offered to prolong the tour with a single question. They stumbled after Carmody, exchanging haggard looks.

At last, when Willie was honestly expecting to faint and even looking forward to it, Carmody said, “Well, I guess that does it.” He led them forward to the well deck. “Just one more thing now. You climb that mast.”

It was a wooden pole topped by a radar, and it looked about five hundred feet high. “What the hell for?” whined Willie. “A mast is a mast. I see it, that’s enough.”

“You’re supposed to explore the ship,” said Carmody, “from the bilges to the crow’s-nest.

There’s

the crow’s-nest.” He pointed to a tiny square iron grille at the very top of the mast.

“Can’t we do that tomorrow? I’m a tired old man,” said Harding, with a wistful smile. His face was youthful and kindly; his hair receded deeply at the crown, leaving only a narrow blond peak in the middle. He was slight and had pallid blue eyes.

Carmody said, “I’m supposed to report compliance prior to dinner. If you don’t climb that mast I can’t report compliance.”

“I have three kids,” said Harding, shrugging and setting his foot on the lowest of the metal brackets that studded the mast to the top. “Hope I see ’em again.”

Slowly, painfully, he began to go up. Willie followed, clutching each bracket convulsively. He kept his eyes on the seat of Harding’s trousers, ignoring the dizzying view around him. The wind flapped his sweat-soaked shirt. They reached the crow’s-nest in a couple of minutes. As Harding scrambled up on the platform Willie heard the ugly thump of a skull striking metal.

“Ouch! Christ, Keith, watch out for this radar,” moaned Harding.

Willie crawled onto the crow’s-nest on his stomach. There was barely room on the rickety grille for the two men side by side. They sat with feet dangling into empty blue space.

“Well done!” came Carmody’s voice thinly from below. “Good-by now. I’m going to report compliance.”

He disappeared into a passageway. Willie stared down at the faraway deck, then quickly pulled his eyes away and took in the surrounding view. It was a fine one. The harbor sparkled beneath them, plain as a map in all its contours. But Willie took no pleasure in it. The height made him shudder. He felt he could never climb down again.

“I regret to tell you,” said Harding in a small voice, his hand to his forehead, “that I am going to have to vomit.”

“Oh, Christ, no,” said Willie.

“Sorry. Height bothers me. I’ll try to keep from getting any on you. Jesus, though, all those guys down below. It’s awful.”

“Can’t you hold off?” begged Willie.

“Not a chance,” said Harding, his face a poisonous green. “Tell you what, though. I can do it in my hat.” He pulled off his officer’s cap, adding, “Though I hate to. It’s my only hat-”

“Here,” said Willie swiftly, “I have two others.” He offered Harding his new officer’s cap, upside down.

“This is damned cordial of you,” gasped Harding.

“You’re perfectly welcome,” said Willie. “Help yourself.”

Harding threw up neatly into the extended hat. Willie felt a terrible urge to do likewise, but he fought it down. Harding’s color improved somewhat. “God, thanks, Keith. Now what do we do with it?”

“Good question,” said Willie, staring at the mournful object in his hands. “A hatful of-that-is an unhandy thing.”

“Scale it out over the side.”

Willie shook his head. “It might turn over. Wind might catch it.”

“It’s a cinch,” said Harding, “you can’t put it back on.”

Willie unfastened the chin strap and looped the hat carefully to a corner of the crow’s-nest, bucket-fashion. “Let it hang here forever,” said Willie, “as your salute to the

Caine.”

“I can never get down from here,” Harding said feebly. “You go ahead. I’ll die and rot here. Nobody will miss me except my family.”

“Nonsense. Do you really have three kids?”

“Sure. My wife’s on the way to a fourth.”

“What the hell are you doing in the Navy?”

“I’m one of those silly jerks who thought he had to fight the war.”

“Feeling better?”

“A little, thanks.”

“Come on,” said Willie. “I’ll go first. You won’t fall. If we stay up here much longer we’ll get so sick we’ll both fall off.”

The descent was an endless slippery horror. Willie’s sweating hands slid on the shallow brackets, and at one ghastly point his foot slipped. But they both reached the deck. Harding tottered, his face beaded with drops. “I’m going to lie down and kiss the deck,” he muttered.

“There are sailors around,” whispered Willie. “It’s all in the day’s work. Come on, let’s hit the clip shack.”

There were two bunks in the little tomb now. Harding dived into the bottom one, and Willie fell on the top bunk. For a while they lay silently, panting. “Well,” spoke Harding wearily at last, “I’ve heard of friendships sealed in blood, but never in puke. All the same, Keith, I’m obliged to you. You did a noble deed with your hat.”

“I’m just lucky,” said Willie, “that you didn’t have to do the same for me. No doubt you’ll have plenty of chance on this happy cruise.”

“Any time,” said Harding, his voice trailing off. “Any time, Keith. Thanks again.” He rolled over and fell asleep.

It seemed to Willie that he had barely dozed off when a hand reached into his bunk and shook him. “Chadan, suh,” said the voice of Whittaker, and his steps receded on the deck outside.

“Harding,” groaned Willie, “do you want dinner?”

“Huh? Dinner already? No. Sleep is what I want-”

“We’d better go. It’ll look bad if we don’t.”

There were three officers at the wardroom table including the captain. The rest were off on shore leave. Willie and Harding took chairs at the lower end of the long white cloth and began eating in silence. The others ignored them and made incomprehensible jokes among themselves about things that had happened at Guadalcanal and New Zealand and Australia. Lieutenant Maryk was the first to glance their way. He was burly, round-faced, and pugnacious-looking, about twenty-five, with a prison haircut. “You guys look kind of red-eyed,” he said.

Willie said, “We were caulking off for a few minutes in the clip shack.”

“Nothing like caulking off to start your career right,” the captain said to a pork chop, out of which he took a large bite.

“Kind of hot in there, isn’t it?” said Adams, the gunnery officer. Lieutenant Adams wore fresh prim khakis. He had the long aristocratic face and negligent superior look which Willie had seen often at Princeton. It meant good family and money.

“Kind of,” Harding said meekly.

Maryk turned to the captain. “Sir, that doggone clip shack is over the engine room. These guys’ll fry in there-”

“Ensigns are expendable,” the captain said.

“What I mean, sir, I think I could hang a couple of bunks just as easy in Adams’ and Gorton’s room, or even in here over the couch-”

“The hell with that,” Adams said.

“Isn’t that a hull modification, Steve?” the captain said, chewing pork. “You’d have to get permission from BuShips.”

“I can look it up, sir, but I don’t think it is.”

“Well, when you get around to it. The shipfitters are way behind as it is.” Captain de Vriess glanced at the ensigns. “Do you gentlemen think you can survive a week or two in the clip shack?”

Willie was tired, and the sarcasm irritated him. “Nobody’s complaining,” he said.

De Vriess raised his eyebrows and grinned. “That’s the spirit, Mr. Keith.” He turned to Adams. “Have these gentlemen started on their officers’ qualification courses yet?”

“No, sir-Carmody had them all afternoon, sir-”

“Well, Mr. Senior Watch Officer, time’s a-wasting. Get them started after dinner.”

“Aye aye, Captain.”

The officers’ qualification courses were bulky mimeographed sheafs of coarse paper turning brown around the edges. They were dated 1935. Adams brought them out of his room while the ensigns were still drinking coffee, and handed a course to each of them. “There are twelve assignments,” he said. “Complete the first by 0900 tomorrow and leave it on my desk. Thereafter complete one a day while in port and one every three days while at sea.”

Willie glanced at the first assignment:

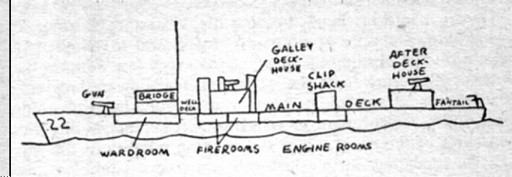

Make two sketches of the Caine, port and starboard, showing every compartment and stating the use of each

.

“Where do we get this information, sir?”

“Didn’t Carmody take you around the ship?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, just write down what he told you, in diagram form.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Willie.

Adams left the two ensigns to themselves. Harding murmured wearily, “What say? Want to start on it?”

“Do you remember anything Carmody said?”

“Just one thing. ‘Climb that mast.’ ”

“Well, it’s due first thing in the morning,” Willie said. “Let’s have a go at it.”

They collaborated over a sketch, blinking and yawning, with frequent arguments about details. At the end of an hour their work looked like this:

Willie sat back and examined it critically. “I think that does it-”

“Are you crazy, Keith? There are about forty compartments we have to stick in a label-”

“

I

don’t remember any of those bloody compartments-”

“Neither do I. Guess we’ll just have to go around the ship again-”

“What, for another three hours? Man, I’ll get a heart attack. I’m failing fast. Look, my hands are shaking-”

“Anyway, Keith, the whole thing’s out of proportion. It looks like some misbegotten tugboat-”

“It is.”

“Look, I have an idea. There must be blueprints of this ship somewhere. Why don’t we just get hold of them and- It’s not cricket maybe but-”

“Say no more! You’re a genius, Harding! That’s it. We’ll do

exactly

that. First thing in the morning. Me for the Black Hole.”

“Right with you.”

Outside the clip shack, under a brilliant yellow floodlight, some civilian yard workers were burning with blowtorches and sawing and banging at the deck, installing a new life-raft rack. Harding said, “How the devil can we sleep with that going on?”

“I could sleep,” said Willie, “if they were doing all that to me instead of to the deck. Let’s go.” He stepped into the shack and backed out, coughing like a consumptive. “Ye gods!”

“What’s the matter?”

“Go in there and take a breath-a shallow one.”

The shack was full of stack gas. A shift in the wind was wafting the fumes from number-three stack directly into the little hut, where, having no place to go, they stayed and fermented. Harding took a sniff at the doorway and said, “Keith, it’s suicide to sleep in there-”

“I don’t care,” Willie said desperately, pulling off his shirt, “I’d just as lief die, all things considered.”