The Cats in the Doll Shop (3 page)

Read The Cats in the Doll Shop Online

Authors: Yona Zeldis McDonough

“Where did you get that?” Trudie asks. Cream is a luxury in our home. Mama does not buy it often.

“I took just a little while Mama was busy talking to Mrs. Kornblatt.”

“What if she finds out?” Trudie asks.

“It's for a good cause,” Sophie says. “She'll understand.”

I ponder that. Papa and Mama are in favor of good causes, and encourage us to perform small acts of

tzedakah

âcharityâwhenever we can.

tzedakah

âcharityâwhenever we can.

“Well, I guess it will be all right then. . . .” Trudie says.

“Of course it will,” says Sophie. “Just look at her! Don't you think she needs help?”

The cat sits down on her haunches. She seems to be looking directly at me with her big, amber eyes. I look back at her. Yes, I decide. Sophie is right.

We set the box near the brick wall and place the saucer of cream next to it.

“How will she get over the wall to reach the box?” asks Trudie.

“Cats are good climbers,” I say.

“Even cats that are going to have kittens?”

Trudie has a point. But we can't get over the wall, so we have no other choice.

“If she really wants to, she can climb over,” Sophie says.

Just at that moment, we hear our mother's voice. “Trudie! Anna! Sophie!” she called. “Time for supper! Come inside to wash your hands.”

“My hands are

clean

,” grumbles Trudie, but she follows us to the sink just the same.

clean

,” grumbles Trudie, but she follows us to the sink just the same.

When we are all seated round the small oak table in our little kitchen, Mama sets the blue-and-white platter of corned beef and cabbage down in front of us. Fragrant steam rises off the food.

While I am mopping up the tasty liquid from the cabbage with a slice of fresh rye bread, Mama tells us about the most recent letter she received from Aunt Rivka. Tania's boat is sailing on the fifteenth of September. Today is the fourthâthat's eleven days off.

“That means she'll be here soon!” I exclaim. “But not for Rosh Hashanah.” Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, is on the eighth, and Mama has invited a few people over for dinner to celebrate with us: our next door neighbors the Kleins, Mrs. Schwebel, a widow from our

shul

, and Mr. Umansky, one of Papa's old friends.

shul

, and Mr. Umansky, one of Papa's old friends.

“No, not for the holiday,” says Mama. She begins to clear the plates and sets out the bowl of stewed fruit for dessert.

“How long does it take to get here on the boat?” Trudie asks.

“The crossing takes about two weeks,” Mama replies.

“Which is not as long as when we did it,” Papa points out. He helps himself and then passes the bowl around.

“So if she leaves on the fifteenth, that means she'll get here on the twenty-ninth,” I say, doing the arithmetic in my head.

“The date is not exact,” Mama says, taking a spoonful of her fruit. “It's just an approximation. We'll look for the notice of the ship's arrival in the newspaper. That's where it's announced.”

When we have all finished dessert, I help Mama clean up while Sophie and Trudie work on their lessons. Our kitchen is compact but efficient. It contains a deep sinkâthe only one we have, so we use it for washing up, brushing our teeth, and filling our water pitcher. We are lucky to have both a stove and an icebox. Not all our neighbors do. And our bathtub is in the kitchen, covered with a hinged piece of wood when we are not using it. Mama stands a folding screen in front of it whenever someone takes a bath.

“Mama, tell me about the crossing,” I say as I bring the plates to the sink. The word has stayed with me ever since Mama said it at supper; it makes the ocean journey sound like a grand adventure. I know my parents made “the crossing” years ago, before they had us or even had met each other. Papa came with his mother and two brothers. Mama's parents had died, so she came with her aunt, uncle, and cousins. But I don't know the details. “Was it exciting? Was it fun?”

“Fun?” Mama turns to look at me. “No, I wouldn't have called it fun. The boat was filthy and crowded. Sometimes the ocean was rough. There were big storms that made the waves swell. We were so frightened. And on top of that, everyone got seasick.”

“Did you?” I ask.

“Almost every day,” she says. “It was terrible. Throwing up, headachesâI was never so sick in my life.” She stops washing the plate she is holding.

“That does sound terrible,” I say.

“And here's something I haven't thought of in years.” Mama puts the plate in the dish rack and sits down on a chair. “I had a doll with me on the trip. Just a little rag doll, but she was the only doll I had. My mother had made her for me when I was just a tiny girl.”

“Really?” Mama never told me this before. “What was her name?”

“Suki.” Mama smiles. “Isn't that a funny name? She had two little black buttons for eyes, and her mouth was a red X that had been sewn on with embroidery thread.”

“You must have loved her,” I say.

“I did,” Mama agrees. “And when we were on the boat, I lost her.”

“Lost her!” I exclaim. “How sad!”

“It was,” says Mama. “I cried and cried. My aunt made me another doll, but it wasn't the same.” She gets up from the chair. “Well, the dishes aren't going to get done by sitting around and thinking about the past, are they?” She reaches for another plate. “I only hope Tania has a better time of it. She won't have her mother or an aunt with her, after all. She'll be with a friend of Aunt Rivka's. . . .” sighs Mama.

As soon as we are through in the kitchen. I go in search of my books so I can start my spelling lesson.

“The crossing” no longer sounds like a great adventure. Instead, it sounds, well, awful. I am glad I do not have to do it. But Tania does. Before I settle down to work, I take Bernadette Louise from her place in our room. She always makes me feel better when I am worried about something. Looking at her smooth, glazed face, I realize that she made a “crossing,” too, when she was first brought over from Germany. And although she is not human, the trip was still dangerous. She could easily have gotten broken or lost. Instead, she had a safe trip and ended up here with me. I find myself wishing, hard, that Tania will be as lucky.

3

A

SWEETYEAR

SWEETYEAR

We have just finished our poetry lesson in school when the dismissal bell rings. I stuff my pencils, books, and papers into my satchel and hurry home with my sisters. We immediately head out through the shop, where Kathleen and Michael are working, to the yard, to check on the cat. She is nowhere to be seen. The box we prepared yesterday is empty, and the cream is untouched except for a few flecks of soot that have settled on its surface. Trudie and I are both horrified as we watch Sophie pour it into the dirt.

“Well, we can't give her cream that's been sitting out all night, can we? It may be spoiled.”

I suppose she is right, though the waste of it bothers me. But the absence of the cat bothers me even more.

“Where do you suppose she went?” I ask Sophie. “She looked like she was going to have those kittens soon.”

“I know,” Sophie says. “But we've done everything we can, haven't we?”

“Maybe we can try to tempt her with something else,” I say. “Something she won't be able to resist.”

“Mama said we're having fish soup tonight,” Trudie pipes up. “I'll bet she's upstairs in the kitchen making it right now.”

“Cats love fish,” Sophie declares in that know-it-all way of hers. She turns to Trudie. “If Mama is making fish soup, there will be fish scraps. Go inside and get some from the garbage pail.”

“I don't want to,” whines Trudie.

“Why not?” Sophie demands.

“They smell so bad,” Trudie says.

“So what?” Sophie admonishes. “The cat will think those smelly old scraps are the most delicious treat in the world.” Trudie stops whining and goes inside.

While she is gone, I look over at the third-story fire escape where we saw the cat yesterday.

“What's that?” I ask Sophie.

“What's what?”

“That gray thing. In the corner.”

She follows my gaze upward. “It looks like a blanket.”

I nod. It

is

a blanket.

is

a blanket.

“Do you think someone left it there for the cat?” I ask. Sophie and I continue to look.

“No,” she says finally. “It's not folded or laid out nicely. It's just stuffed in the corner. As if it's trash.” And I have to agree.

Trudie returns with the fish scraps in a clean saucer.

“Did Mama ask you what you wanted them for?” Sophie asks.

“I took them from the garbage. Just like you said. She didn't notice.”

“Good,” says Sophie, setting the saucer in the box.

“You don't want Mama and Papa to know what we're doing?” Trudie asks.

“Not exactly,” Sophie.

“Why not?” I ask.

“You know how Papa is about cats and dogs living inside,” Sophie reminds me. It's true. Whenever we have asked about getting a kitten or a puppy Papa has always said no. He told us how back in Russia, no one kept animals like that in the house. He said there were cats where he lived, but they had to catch their own food and never came inside. So he probably won't like our feeding this cat. With a last glance at the blanket on the fire escape across the yard, we troop inside to start our lessons.

In the days before Tania gets here, Mama doesn't receive any more letters from Aunt Rivka. But we have plenty to keep us busy. Rosh Hashanah is coming, and we all pitch in to prepare for the big dinner that Mama makes on the eve of the holiday.

There is a lot to do: polishing, ironing, sweeping, and dusting. We add two leaves to the table, so that there will be enough room for everyone to sit down. Mama roasts two chickens and bakes three round loaves of her delicious golden challah. She also prepares

tzimmes

with carrots, prunes and chunks of pumpkin; sponge cake; and slices of apple dipped in honey. Tradition says that this will make the new year sweet.

tzimmes

with carrots, prunes and chunks of pumpkin; sponge cake; and slices of apple dipped in honey. Tradition says that this will make the new year sweet.

I don't have much time to think about Tania, or about the cat out back either. But when I do think of Tania, I feel a pleasant tingle of anticipation. Since we are the same age, she won't act like a baby, the way Trudie still does at times. Just the other day, she scribbled on a drawing I was doing for school. When I told Papa, she burst out crying, like it was all my fault. And Tania won't treat

me

like a baby, the way Sophie sometimes does. No, with Tania, everything will be just right.

me

like a baby, the way Sophie sometimes does. No, with Tania, everything will be just right.

Our

erev

Rosh Hashanah dinner is a success. Mr. Umansky, Papa's friend from

shul

, presents me with a bouquet of flowers when I open the door. I giggle as I reach into the cabinet for a vase. Once we are seated, everyone exclaims over how pretty the table looks. Since I was the one to set it, I feel especially pleased. Mr. Klein eats three helpings of

tzimmes

, and we all devour Mama's delicious challah. Only a few crumbs, which Mama will scatter to the sparrows that gather on the sidewalk in front of the shop, are left. After dinner, some of the guests start singing songs that they learned in the old country. Mama sings a ballad in Yiddish. I don't understand the words, but the melody is so pretty it makes me go quiet for a few minutes. At the end, everyone claps, and I feel so proud of her.

erev

Rosh Hashanah dinner is a success. Mr. Umansky, Papa's friend from

shul

, presents me with a bouquet of flowers when I open the door. I giggle as I reach into the cabinet for a vase. Once we are seated, everyone exclaims over how pretty the table looks. Since I was the one to set it, I feel especially pleased. Mr. Klein eats three helpings of

tzimmes

, and we all devour Mama's delicious challah. Only a few crumbs, which Mama will scatter to the sparrows that gather on the sidewalk in front of the shop, are left. After dinner, some of the guests start singing songs that they learned in the old country. Mama sings a ballad in Yiddish. I don't understand the words, but the melody is so pretty it makes me go quiet for a few minutes. At the end, everyone claps, and I feel so proud of her.

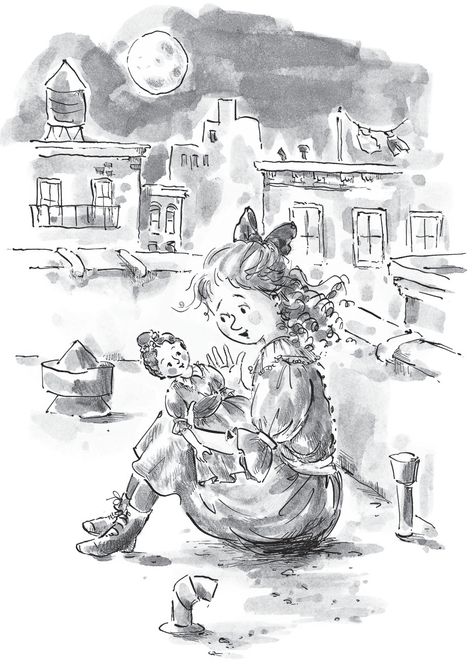

The beautiful weather has continued, and even though it is nighttime, I have the sudden urge to go up on the roof. I ask my sisters if they want to join me. But Sophie doesn't want to, and Trudie is too tired. So I take Bernadette Louise under my arm and head up to the roof myself. I probably should ask my parents, but they are so busy with our company I decide I won't bother. Besides, I won't stay up there for very long.

Since the time Bernadette Louise actually became mine forever and always, I have sewed her several new outfits, including a tweed cape, a calico skirt and blouse, and a dark green corduroy suit. I've been sewing since I was a little girl. Mama, who can sew just about anything, taught all of us early on, and though I am not as talented as she is, the clothes turned out all right. Tonight Bernadette Louise wears a dress made from blue polished cotton with a red ribbon at her waist. The fabric was left over from material that Mama used for a dress of mine.

Other books

Sparta by Roxana Robinson

Twisted Heart by Maguire, Eden

The Mark of the Golden Dragon by Louis A. Meyer

Middle School: My Brother Is a Big, Fat Liar by James Patterson

Love the One You're With by Emily Giffin

A Dream of Daring by LaGreca, Gen

Luncheon of the Boating Party by Susan Vreeland

Analog SFF, March 2012 by Dell Magazine Authors

Died with a Bow by Grace Carroll

Apocalypse Cow by Logan, Michael