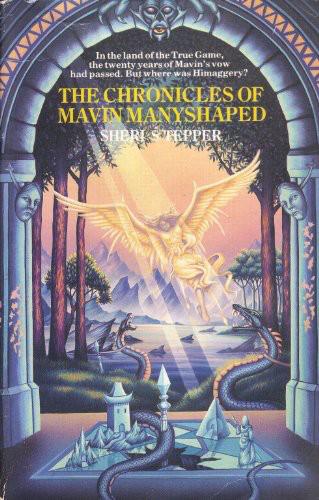

The Chronicles of Mavin Manyshaped

The Chronicles of Mavin Manyshaped by Sheri S. Tepper

THE FLIGHT OF MAVIN MANYSHAPED

THE SEARCH OF MAVIN MANYSHAPED

THE SONG OF MAVIN MANYSHAPED

CHAPTER ONE

Around the inner maze of Danderbat keep—with its hidden places for the elders, its sleeping chambers, kitchens and nurseries—lay the vaster labyrinth of the outer p’natti: slything walls interrupted by square-form doors, an endless array of narrowing pillars, climbing ups and slithering downs, launch platforms so low as to require only leaping legs and others so high that wings would be the only guarantee of no injury.

Through the p’natti the shifters of all the Xhindi clans came each year at Assembly time, processions of them, stiff selves marching into the outer avenues only to melt into liquid serpentines which poured through the holes in the slything walls; into tall wands of flesh sliding through the narrowing doors; into pneumatic billows bounding over the platforms and up onto the heights; all in a flurry of wings, feathers, hides, scales, conceits and frenzies which dazzled the eyes and the senses so that the children became hysterical with it and hopped about on the citadel roof as though an act of will could force them all at once and beforetime into that Talent they wanted more than any other. Every year the family Danderbat changed the p’natti; new shaped obstacles were invented; new requirements placed upon the shifting flesh which would pass through it to the inner maze, and every year at Assembly the shifters came, foaming at the outer reaches like surf, then plunging through the reefs and cliffs of the p’natti to the shore of the keep, the central place where there were none who were not shifters—save those younglings who were not sure yet what it was they were.

Among these was Mavin, a daughter of the shapewise Xhindi, form-family of Danderbat the Old Shuffle, a girl of some twelve or fourteen years. She was a forty-season child, and expected to show something pretty soon, for shifters came to it young and she was already older than some. There were those who had begun to doubt s he would ever come through the p’natti along the she-road reserved for females not yet at or through their child-bearing time. Progeny of the shifters who turned out not to have the Talent were sent away to be fostered elsewhere as soon as that lack was known, and the possibility of such a journey was beginning to be rumored for Mavin.

She had grown up as shifter children do when raised in a shifter place, full of wild images and fluttering dreams of the things she would become when her Talent flowered. As it happened, Mavin was the only girl child behind the p’natti during that decade, for Handbright Ogbone, her sister, was a full decade older and in possession of her Talent before Mavin was seven. There were boys aplenty and overmuch, some saying with voices of dire prophecy that it was a plague of males they had, but the Ogbone daughters were the only females born to be reared behind the Danderbat p’natti since Throsset of Dowes, and Throsset had fled the keep as long as four years before. Since there were no other girls, the dreams which Mavin shared were boyish dreams. Handbright no longer dreamed, or if she did, she did not speak of it.

Mavin’s own mother, Abrara Ogbone, had died bearing the boy child, Mertyn—caught by the shift-devil, some said, because she had experimented with forbidden shapes while she was pregnant. No one was so heartless as to say this to Mavin directly, but she had overheard it without in the least understanding it several times during her early years. Now at an age where her own physical maturity was imminent, she understood better what they had been speaking of, but she had not yet made the jump of intuition which applied this knowledge to herself. She had a kind of stubborn naivete about her which resisted learning some of the things which other girls got with their mother’s milk. It was an Ogbone trait, though she did not know it. She had not before now understood flirting, for example, or the reasons why the men were always the winners of the processional competitions, or why Handbright so often cried in corners or was so weary and sharp-tongued. It wasn’t that she could not have understood these things, but more that she was so busy apprehending everything in the world that she had not had time before to make the connections among them.

She might have been enlightened by overhearing a conversation between two hangers-on of the Old Shuffle—two of the guards cum hunters known as “the Danderbats” after Theobald Danderbat, forefather and tribal god, direct line descendent, so it was said, from Thandbar, the forefather of all shifters—who kept themselves around the keep to watch it, they said, and look after its provisioning. So much time was actually spent in the provisioning of their drinking and lechery that little enough energy was left for else.

“Everytime I flex a little, I feel eyes,” Gormier Graywing was saying. “She’s everwhere. Anytime I’ve a mind to shift my fingers to get a better grip on something, there she is with her eyes on my hands and, like as not, her hand on mine to feel how the change goes. If there’s such a thing as a’ everwhere shifter child, it’s this she-child, Mavin.” Gormier was a virile, salacious old man thing, father of a half-dozen non-shifter whelps and three true-bred members of the clan. He ran a boneless ripple now, down from shoulders through fingers, a single tentacle wriggle before coming back to bone shape in order to explain how he felt. Some of the Danderbats would carry on whole conversations in muscle talk without ever opening their mouths. “Still, there’s never a sign she knows she’s female and I’m male, her not noticing she gives me a bit of tickle.”

“ ‘Tisn’t child flirtiness.” The other speaker was Haribald Halfmad, so named in his years in Schlaizy Noithn and never, to his own satisfaction, renamed. “There’s no sexy mockery there. Just that wide-eyed kind of oh-my look what you’d get from a baby with its first noisy toy. She hasn’t changed that look since she was a nursling, and that’s what’s discomfiting about her. When she was a toddler, there was some wonder if she was all there in the brain net, and she was taken out to a Healer when she was six or so, just to see.”

“I didn’t know that! Well then, it must have been taken serious; we Old Shuffle Xhindi don’t seek Healers for naught.”

“We Danderbats don’t seek Healers at all, Graywing, as you well know, old ox. It was her sister Handbright took her, for they’re both Ogbones, daughter of Abrara Ogbone—she that has a brother up Battlefox way. But that was soon after the childer’s mother died, so it was forgiven as a kind of upset, though normally the Elders would have had Handbright in a basket for it. Handbright brought her back saying the Healer found nothing wrong with the child save sadness, which would go away of itself with time. Since then the thought’s been that she’s a mite slow but otherwise tribal as the rest of us. I wish she’d get on with it, for I’ve a mind to try her soon as her Talent’s set.” And he licked his lips, nudging his fellow with a lubricious elbow. “If she doesn’t get on with it, I may hurry things a bit.”

The object of this conversation was sitting at the foot of a slything column in the p’natti, in full sight of the two old man things but as unconscious of them as though she had been on another world. Mavin had just discovered that she could change the length of her toes.

The feeling was rather but not entirely like pain. There was a kind of itchy delight in it as well, not unlike the delight which could be evoked by stroking and manipulating certain body parts, but without that restless urgency. There was something in it, as well, of the fear of falling, a kind of breathless gap at the center of things as though a misstep might bring sudden misfortune. Despite all this, Mavin went on with what she was doing, which was to grow her toes a hand’s-width longer and then make them shorter again, all hidden in the shadow of her skirts. She had a horrible suspicion that this bending and extending of them might make them fall off, and in her head she could see them wriggling away like so many worms, blind and headless, burrowing themselves down into the ground at the bottom of the column, to be found there a century hence, still squirming, unmistakably Mavin’s toes. After a long time of this, she brought her toes back to a length which would fit her shoes and put them on, standing up to smooth her apron and noticing for the first time the distant surveillance offered by the two granders on the citadel high porch. She made a little face, as she had seen Handbright do, remotely aware of what the two old things usually chatted about but still not making any connection between that and herself. She was off to tell Handbright about her toes, and there was room for nothing else in her head at the moment, though she knew at the edges of her consciousness the oldsters had been talking man-woman stuff.

But then everyone was into man-woman stuff that year. Some years it was fur, and some years it was feathers. Some years it was vegetable-seeming which was the fad, and other years no one cared for anything except jewels. This year was sex form changing, and it was somewhat titillating for the children, seeing their elder relatives twisting themselves into odd contorted shapes with nerve ends pushed out or tucked in in all sorts of original ways. Despite the fact that shifters had no feeling of shame over certain parts—those parts being changed day to day in suchwise that little of the original topography could still be attached to them—the younglings who had not become shifters yet were tied to old, non-shifter forebear emotions which had to do with the intimate connections between things excretory and things erotic. It could not be helped. It was in the body shape they were born with and in the language and in the old stories children were told, and in the things all children did and thought and said, ancient as apes and true as time. So the children, looking upon all this changing about, found a kind of giggly prurience in it despite the fact that they were shifter children every one, or hoped they were soon to be.

All this lewd, itchy stuff to do with man and woman made Mavin uncomfortable in a deep troublesome way. It was by no means maidenly modesty, which at one time it would have been called. It was a deeper thing than that—a feeling that something indecent was being done. The same feeling she had when she saw boys pulling the wings off zip-birds and taunting them as they flopped in the dust, trying, trying, trying to fly. It was that same sick feeling, and since it seemed to be part and parcel of being shifter, Mavin decided she wouldn’t tell anyone except Handbright she was shifter, not just yet.

Instead, she smoothed her apron, pointedly ignored the speculative stares of old Graywing and Haribald, and walked around the line of slything pillars to a she-door. At noon would be a catechism class, and though Mavin made it a practice to avoid many things which went on in Danderbat keep, it was not wise to avoid those. Particularly inasmuch as Handbright was teaching it and Mavin’s absence could not pass unnoticed. Since she was the only girl, it would not pass unnoticed no matter who was teaching, but she did not need to remind herself of that.

Almost everyone was there when she arrived, so she slipped into a seat at the side of the room, attracting little attention. Some of the boys were beginning to practice shifter sign, vying with one another who could grow the most hair on the backs of their hands and arms, who could give the best boneless wriggle in the manner of the Danderbats. Handbright told them once to pay attention, then struck hard at the offending arms with her rod, at which all recoiled but Tolerable Titdance, who had grown shell over his arms in the split second it had taken Handbright to hit at him. He laughed in delight, and Handbright smiled a tired little smile at him. It was always good to see a boy so quick, and she ruffled his hair and whispered in his ear to make him blush red and settle down.