The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (12 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

In the twentieth century improvements in transportation and communication and global interdependence increased tremendously the costs of exclusion. Except for small, isolated, rural communities willing to exist at a subsistence level, the total rejection of modernization as well as Westernization is hardly possible in a world becoming overwhelmingly modern and highly interconnected. “Only the very most extreme fundamentalists,” Daniel Pipes writes concerning Islam, “reject modernization as well as Westernization. They throw television sets into rivers, ban wrist watches, and reject the internal combustion engine. The impracticality of their program severely limits the appeal of such groups, however; and in several cases—such as the Yen Izala of Kano, Sadat’s assassins, the Mecca mosque attackers, and some Malaysian

dakwah

groups—their defeats in violent encounters with the authorities caused them then to disappear with few traces.”

[36]

Disappearance with few traces summarizes generally the fate of purely rejectionist policies by the end of the twentieth century. Zealotry, to use Toynbee’s term, is simply not a viable option.

A second possible response to the West is Toynbee’s Herodianism, to embrace both modernization and Westernization. This response is based on the assumptions that modernization is desirable and necessary, that the indigenous culture is incompatible with modernization and must be abandoned or abolished, and that society must fully Westernize in order to successfully modernize. Modernization and Westernization reinforce each other and have to go together. This approach was epitomized in the arguments of some late nineteenth century Japanese and Chinese intellectuals that in order to modernize, their societies should abandon their historic languages and adopt English as their national language. This view, not surprisingly, has been even more popular among Westerners than among non-Western elites. Its message is: “To be successful, you must be like us; our way is the only way.” The argument is that “the religious values, moral assumptions, and social structures of these [non-Western] societies are at best alien, and sometime hostile, to the values and practices of industrialism.” Hence economic development will “require a radical and destructive remaking of life and society, and, often, a reinterpretation of the meaning of existence itself as it has been understood by the people who live in these civilizations.”

[37]

Pipes makes the same point with explicit reference to Islam:

To escape anomy, Muslims have but one choice, for modernization requires Westernization. . . . Islam does not offer an alternative way to modernize. . . . Secularism cannot be avoided. Modern science and technology require an absorption of the thought processes which accompany them; so too with political institutions. Because content must be emulated no less than form, the predominance of Western civilization must be acknowledged so as to be

p. 74

able to learn from it. European languages and Western educational institutions cannot be avoided, even if the latter do encourage freethinking and easy living. Only when Muslims explicitly accept the Western model will they be in a position to technicalize and then to develop.

[38]

Sixty years before these words were written Mustafa Kemal Ataturk had come to similar conclusions, had created a new Turkey out of the ruins of the Ottoman empire, and had launched a massive effort both to Westernize it and to modernize it. In embarking on this course, and rejecting the Islamic past, Ataturk made Turkey a “torn country,” a society which was Muslim in its religion, heritage, customs, and institutions but with a ruling elite determined to make it modern, Western, and at one with the West. In the late twentieth century several countries are pursuing the Kemalist option and trying to substitute a Western for a non-Western identity. Their efforts are analyzed in

chapter 6

.

Rejection involves the hopeless task of isolating a society from the shrinking modern world. Kemalism involves the difficult and traumatic task of destroying a culture that has existed for centuries and putting in its place a totally new culture imported from another civilization. A third choice is to attempt to combine modernization with the preservation of the central values, practices, and institutions of the society’s indigneous culture. This choice has understandably been the most popular one among non-Western elites. In China in the last stages of the Ch’ing dynasty, the slogan was

Ti-Yong,

“Chinese learning for the fundamental principles, Western learning for practical use.” In Japan it was

Wakon, Yōsei,

“Japanese spirit, Western technique.” In Egypt in the 1830s Muhammad Ali “attempted technical modernization without excessive cultural Westernization.” This effort failed, however, when the British forced him to abandon most of his modernizing reforms. As a result, Ali Mazrui observes, “Egypt’s destiny was not a Japanese fate of technical modernization

without

cultural Westernization, nor was it an Ataturk fate of technical modernization

through

cultural Westernization.”

[39]

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, however, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad ’Abduh, and other reformers attempted a new reconciliation of Islam and modernity, arguing “the compatibility of Islam with modern science and the best of Western thought” and providing an “Islamic rationale for accepting modern ideas and institutions, whether scientific, technological, or political (constitutionalism and representative government).”

[40]

This was a broad-gauged reformism, tending toward Kemalism, which accepted not only modernity but also some Western institutions. Reformism of this type was the dominant response to the West on the part of Muslim elites for fifty years from the 1870s to the 1920s, when it was challenged by the rise first of Kemalism and then of a much purer reformism in the shape of fundamentalism.

Rejectionism, Kemalism, and reformism are based on different assumptions as to what is possible and what is desirable. For rejectionism both moderniza

p. 75

tion and Westernization are undesirable and it is possible to reject both. For Kemalism both modernization and Westernization are desirable, the latter because it is indispensable to achieving the former, and both are possible. For reformism, modernization is desirable and possible without substantial Westernization, which is undesirable. Conflicts thus exist between rejectionism and Kemalism on the desirability of modernization and Westernization and between Kemalism and reformism as to whether modernization can occur without Westernization.

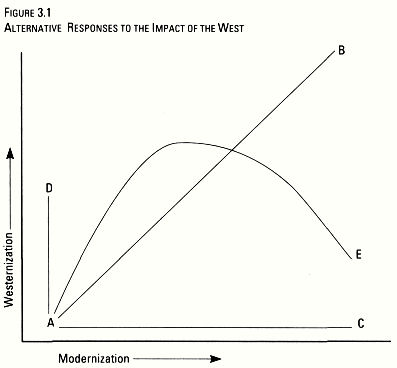

Figure 3.1 – Alternative Responses to the Impact of the West

Figure 3.1

diagrams these three courses of action. The rejectionist would remain at Point A; the Kemalist would move along the diagonal to Point B; the reformer would move horizontally toward Point C. Along what path, however, have societies actually moved? Obviously each non-Western society has followed its own course, which may differ substantially from these three prototypical paths. Mazrui even argues that Egypt and Africa have moved toward Point D through a “painful process of cultural Westernization

without

technical modernization.” To the extent that any general pattern of modernization and Westernization exists in the responses of non-Western societies to the West, it would appear to be along the curve A-E. Initially, Westernization and modernization are closely linked, with the non-Western society absorbing substantial elements of Western culture and making slow progress toward modernization. As the pace of modernization increases, however, the rate of Westernization

p. 76

declines and the indigenous culture goes through a revival. Further modernization then alters the civilizational balance of power between the West and the non-Western society and strengthens commitment to the indigenous culture.

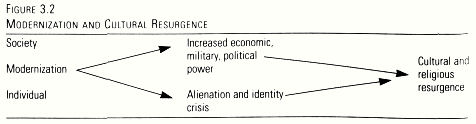

In the early phases of change, Westernization thus promotes modernization. In the later phases, modernization promotes de-Westernization and the resurgence of indigenous culture in two ways. At the societal level, modernization enhances the economic, military, and political power of the society as a whole and encourages the people of that society to have confidence in their culture and to become culturally assertive. At the individual level, modernization generates feelings of alienation and anomie as traditional bonds and social relations are broken and leads to crises of identity to which religion provides an answer. This causal flow is set forth in simple form in

Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 – Modernization and Cultural Resurgence

This hypothetical general model is congruent with both social science theory and historical experience. Reviewing at length the available evidence concerning “the invariance hypothesis,” Rainer Baum concludes that “the continuing quest of man’s search for meaningful authority and meaningful personal autonomy occurs in culturally distinct fashions. In these matters there is no convergence toward a cross-culturally homogenizing world. Instead, there seems to be invariance in the patterns that were developed in distinct forms during the historical and early modern stages of development.”

[41]

Borrowing theory, as elaborated by Frobenius, Spengler, and Bozeman among others, stresses the extent to which recipient civilizations selectively borrow items from other civilizations and adapt, transform, and assimilate them so as to strengthen and insure the survival of the core values or “paideuma” of their culture.

[42]

Almost all of the non-Western civilizations in the world have existed for at least one millennium and in some cases for several. They have a demonstrated record of borrowing from other civilizations in ways to enhance their own survival. China’s absorption of Buddhism from India, scholars agree, failed to produce the “Indianization” of China. The Chinese adapted Buddhism to Chinese purposes and needs. Chinese culture remained Chinese. The Chinese have to date consistently defeated intense Western efforts to Christianize them. If, at some point, they do import Christianity, it is to be expected that it will be absorbed and adapted in such a manner as to be compatible with the central elements of Chinese culture. Similarly, Muslim Arabs received, valued, and made use of their “Hellenic inheritance for essentially utilitarian reasons. Being mostly

p. 77

interested in borrowing certain external forms or technical aspects, they knew how to disregard all elements in the Greek body of thought that would conflict with ‘the truth’ as established in their fundamental Koranic norms and precepts.”

[43]

Japan followed the same pattern. In the seventh century Japan imported Chinese culture and made the “transformation on its own initiative, free from economic and military pressures” to high civilization. “During the centuries that followed, periods of relative isolation from continental influences during which previous borrowings were sorted out and the useful ones assimilated would alternate with periods of renewed contact and cultural borrowing.”

[44]

Through all these phases, Japanese culture maintained its distinctive character.

The moderate form of the Kemalist argument that non-Western societies

may

modernize by Westernizing remains unproven. The extreme Kemalist argument that non-Western societies

must

Westernize in order to modernize does not stand as a universal proposition. It does, however, raise the question: Are there some non-Western societies in which the obstacles the indigenous culture poses to modernization are so great that the culture must be substantially replaced by Western culture if modernization is to occur? In theory this should be more probable with consummatary than with instrumental cultures. Instrumental cultures are “characterized by a large sector of intermediate ends separate from and independent of ultimate ends.” These systems “innovate easily by spreading the blanket of tradition upon change itself. . . . Such systems can innovate without appearing to alter their social institutions fundamentally. Rather, innovation is made to serve immemoriality.” Consummately systems, in contrast, “are characterized by a close relationship between intermediate and ultimate ends. . . . society, the state, authority, and the like are all part of an elaborately sustained, high-solidarity system in which religion as a cognitive guide is pervasive. Such systems have been hostile to innovation.”

[45]

Apter uses these categories to analyze change in African tribes. Eisenstadt applies a parallel analysis to the great Asian civilizations and comes to a similar conclusion. Internal transformation is “greatly facilitated by autonomy of social, cultural, and political institutions.”

[46]

For this reason, the more instrumental Japanese and Hindu societies moved earlier and more easily into modernization than Confucian and Islamic societies. They were better able to import the modern technology and use it to bolster their existing culture. Does this mean that Chinese and Islamic societies must either forgo both modernization and Westernization or embrace both? The choices do not appear that limited. In addition to Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, and, to a lesser degree, Iran have become modern societies without becoming Western. Indeed, the effort by the Shah to follow a Kemalist course and do both generated an intense anti-Western but not antimodern reaction. China is clearly embarked on a reformist path.