The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (44 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

That is clearly not the case with the three “swing” civilizations. Their core states are major actors in world affairs and are likely to have mixed, ambivalent, and fluctuating relationships with the West and the challengers. They also will have varying relations with each other. Japan, as we have argued, over time and with great anguish and soul-searching is likely to shift away from the United States in the direction of China. Like other transcivilizational Cold War alliances, Japan’s security ties to the United States will weaken although probably never be formally renounced. Its relations with Russia will remain difficult so long as Russia refuses to compromise on the Kurile islands it occupied in 1945. The moment at the end of the Cold War when this issue might have been resolved passed quickly with the rise of Russian nationalism, and no reason exists for the United States to back the Japanese claim in the future as it has in the past.

In the last decades of the Cold War, China effectively played the “China card” against the Soviet Union and the United States. In the post-Cold War world, Russia has a “Russia card” to play. Russia and China united would decisively tilt the Eurasian balance against the West and arouse all the concerns that existed about the Sino-Soviet relationship in the 1950s. A Russia working closely with the West would provide additional counterbalance to the Confu

p. 242

cian-Islamic connection on global issues and reawaken in China its Cold War fears concerning an invasion from the north. Russia, however, also has problems with both these neighboring civilizations. With respect to the West, they tend to be more short term; a consequence of the end of the Cold War and the need for a redefinition of the balance between Russia and the West and agreement by both sides on their basic equality and their respective spheres of influence. In practice this would mean:

1. Russian acceptance of the expansion of the European Union and NATO to include the Western Christian states of Central and Eastern Europe, and Western commitment not to expand NATO further, unless Ukraine splits into two countries;

2. a partnership treaty between Russia and NATO pledging nonaggression, regular consultations on security issues, cooperative efforts to avoid arms competition, and negotiation of arms control agreements appropriate to their post-Cold War security needs;

3. Western recognition of Russia as primarily responsible for the maintenance of security among Orthodox countries and in areas where Orthodoxy predominates;

4. Western acknowledgment of the security problems, actual and potential, which Russia faces from Muslim peoples to its south and willingness to revise the CFE treaty and to be favorably disposed toward other steps Russia might need to take to deal with such threats;

5. agreement between Russia and the West to cooperate as equals in dealing with issues, such as Bosnia, involving both Western and Orthodox interests.

If an arrangement emerges along these or similar lines, neither Russia nor the West is likely to pose any longer-term security challenge to the other. Europe and Russia are demographically mature societies with low birth rates and aging populations; such societies do not have the youthful vigor to be expansionist and offensively oriented.

In the immediate post-Cold War period, Russian-Chinese relations became significantly more cooperative. Border disputes were resolved; military forces on both sides of the border were reduced; trade expanded; each stopped targeting the other with nuclear missiles; and their foreign ministers explored their common interests in combating fundamentalist Islam. Most importantly, Russia found in China an eager and substantial customer for military equipment and technology, including tanks, fighter aircraft, long-range bombers, and surface-to-air missiles.

[46]

From the Russian viewpoint, this warming of relations represented both a conscious decision to work with China as its Asian “partner,” given the stagnant coolness of its relations with Japan, and a reaction to its conflicts with the West over NATO expansion, economic reform, arms control,

p. 243

economic assistance, and membership in Western international institutions. For its part, China was able to demonstrate to the West that it was not alone in the world and could acquire the military capabilities necessary to implement its power projection regional strategy. For both countries, a Russian-Chinese connection is, like the Confucian-Islamic connection, a means of countering Western power and universalism.

Whether that connection survives into the longer term depends largely on, first, the extent to which Russian relations with the West stabilize on a mutually satisfactory basis, and, second, the extent to which China’s rise to hegemony in East Asia threatens Russian interests, economically, demographically, militarily. The economic dynamism of China has spilled over into Siberia, and Chinese, along with Korean and Japanese, businesspersons are exploring and exploiting opportunities there. Russians in Siberia increasingly see their economic future connected to East Asia rather than to European Russia. More threatening for Russia is Chinese immigration into Siberia, with illegal Chinese migrants there purportedly numbering in 1995 3 million to 5 million, compared to a Russian population in Eastern Siberia of about 7 million. “The Chinese,” Russian Defense Minister Pavel Grachev warned, “are in the process of making a peaceful conquest of the Russian Far East.” Russia’s top immigration official echoed him, saying, “We must resist Chinese expansionism.”

[47]

In addition, China’s developing economic relations with the former Soviet republics of Central Asia may exacerbate relations with Russia. Chinese expansion could also become military if China decided that it should attempt to reclaim Mongolia, which the Russians detached from China after World War I and which was for decades a Soviet satellite. At some point the “yellow hordes” which have haunted Russian imagination since the Mongol invasions may again become a reality.

Russia’s relations with Islam are shaped by the historical legacy of centuries of expansion through war against the Turks, North Caucasus peoples, and Central Asian emirates. Russia now collaborates with its Orthodox allies, Serbia and Greece, to counter Turkish influence in the Balkans, and with its Orthodox ally, Armenia, to restrict that influence in the Transcaucasus. It has actively attempted to maintain its political, economic, and military influence in the Central Asian republics, has enlisted them in the Commonwealth of Independent States, and deploys military forces in all of them. Central to Russian concerns are the Caspian Sea oil and gas reserves and the routes by which these resources will reach the West and East Asia. Russia has also been fighting one war in the North Caucasus against the Muslim people of Chechnya and a second war in Tajikistan supporting the government against an insurgency that includes Islamic fundamentalists. These security concerns provide a further incentive for cooperation with China in containing the “Islamic threat” in Central Asia and they also are a major motive for the Russian rapprochement with Iran. Russia has sold Iran submarines, sophisticated fighter aircraft, fighter

p. 244

bombers, surface-to-air missiles, and reconnaissance and electronic warfare equipment. In addition, Russia agreed to build lightwater nuclear reactors in Iran and to provide Iran with uranium-enrichment equipment. In return, Russia quite explicitly expects Iran to constrain the spread of fundamentalism in Central Asia and implicitly to cooperate in countering the spread of Turkish influence there and in the Caucasus. For the coming decades Russia’s relations with Islam will be decisively shaped by its perceptions of the threats posed by the booming Muslim populations along its southern periphery.

During the Cold War, India, the third “swing” core state, was an ally of the Soviet Union and fought one war with China and several with Pakistan. Its relations with the West, particularly the United States, were distant when they were not acrimonious. In the post-Cold War world, India’s relations with Pakistan are likely to remain highly conflictual over Kashmir, nuclear weapons, and the overall military balance on the Subcontinent. To the extent that Pakistan is able to win support from other Muslim countries, India’s relations with Islam generally will be difficult. To counter this, India is likely to make special efforts, as it has in the past, to persuade individual Muslim countries to distance themselves from Pakistan. With the end of the Cold War, China’s efforts to establish more friendly relations with its neighbors extended to India and tensions between the two lessened. This trend, however, is unlikely to continue for long. China has actively involved itself in South Asian politics and presumably will continue to do so: maintaining a close relation with Pakistan, strengthening Pakistan’s nuclear and conventional military capabilities, and courting Myanmar with economic assistance, investment, and military aid, while possibly developing naval facilities there. Chinese power is expanding at the moment; India’s power could grow substantially in the early twenty-first century. Conflict seems highly probable. “The underlying power rivalry between the two Asian giants, and their self-images as natural great powers and centers of civilization and culture,” one analyst has observed, “will continue to drive them to support different countries and causes. India will strive to emerge, not only as an independent power center in the multipolar world, but as a counterweight to Chinese power and influence.”

[48]

Confronting at least a China-Pakistan alliance, if not a broader Confucian-Islamic connection, it clearly will be in India’s interests to maintain its close relationship with Russia and to remain a major purchaser of Russian military equipment. In the mid-1990s India was acquiring from Russia almost every major type of weapon including an aircraft carrier and cryogenic rocket technology, which led to U.S. sanctions. In addition to weapons proliferation, other issues between India and the United States included human rights, Kashmir, and economic liberalization. Over time, however, the cooling of U.S.-Pakistan relations and their common interests in containing China are likely to bring India and the United States closer together. The expansion of Indian power in Southern Asia cannot harm U.S. interests and could serve them.

p. 245

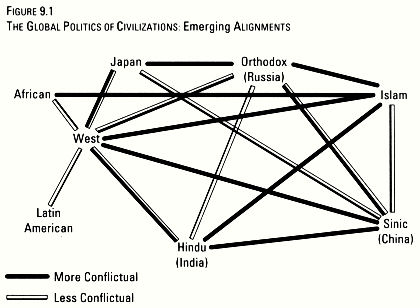

The relations between civilizations and their core states are complicated, often ambivalent, and they do change. Most countries in any one civilization will generally follow the lead of the core state in shaping their relations with countries in another civilization. But this will not always be the case, and obviously all the countries of one civilization do not have identical relations with all the countries in a second civilization. Common interests, usually a common enemy from a third civilization, can generate cooperation between countries of different civilizations. Conflicts also obviously occur within civilizations, particularly Islam. In addition, the relations between groups along fault lines may differ significantly from the relations between the core states of the same civilizations. Yet broad trends are evident and plausible generalizations can be made about what seem to be the emerging alignments and antagonisms among civilizations and core states. These are summarized in

Figure 9.1

. The relatively simple bipolarity of the Cold War is giving way to the much more complex relationships of a multipolar, multicivilizational world.

Figure 9.1 – The Global Politics of Civilizations: Emerging Alignments

Transition Wars: Afghanistan And The Gulf

p. 246

“

L

a premiere guerre civilisationnelle

,” the distinguished Moroccan scholar Mahdi Elmandjra called the Gulf War as it was being fought.

[1]

In fact it was the second. The first was the Soviet-Afghan War of 1979-1989. Both wars began as straightforward invasions of one country by another but were transformed into and in large part redefined as civilization wars. They were, in effect, transition wars to an era dominated by ethnic conflict and fault line wars between groups from different civilizations.

The Afghan War started as an effort by the Soviet Union to sustain a satellite regime. It became a Cold War war when the United States reacted vigorously and organized, funded, and equipped the Afghan insurgents resisting the Soviet forces. For Americans, Soviet defeat was vindication of the Reagan doctrine of promoting armed resistance to communist regimes and a reassuring humiliation of the Soviets comparable to that which the United States had suffered in Vietnam. It was also a defeat whose ramifications spread throughout Soviet society and its political establishment and contributed significantly to the disintegration of the Soviet empire. To Americans and to Westerners generally Afghanistan was the final, decisive victory, the Waterloo, of the Cold War.

For those who fought the Soviets, however, the Afghan War was something else. It was “the first successful resistance to a foreign power,” one Western scholar observed,

[2]

“which was not based on either nationalist or socialist principles” but instead on Islamic principles, which was waged as a jihad, and which gave a tremendous boost to Islamic self-confidence and power. Its impact on the Islamic world was, in effect, comparable to the impact which the Japanese

p. 247

defeat of the Russians in 1905 had on the Oriental world. What the West sees as a victory for the Free World, Muslims see as a victory for Islam.