The Classical World (38 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

Timanthes engraved this star-like lapis lazuli

This Persian semi-precious stone containing gold

For Demylus; in exchange for a tender kiss the dark-haired

Nicaea of Cos re[ceived it as a lovely] gift.

Poseidippus of Pella, 5 (Austin-Bastiniani),

first published from papyrus in 2001

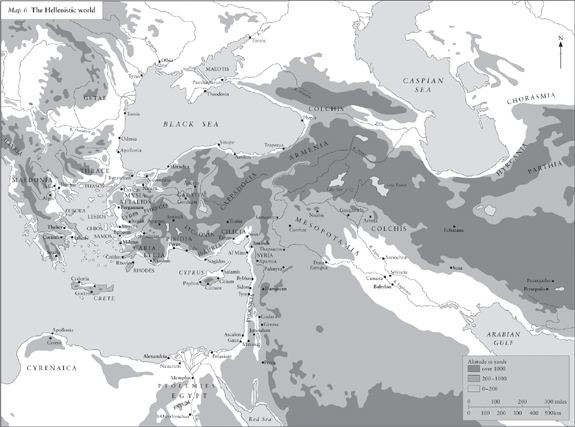

As Alexander’s conquests settled down, the three main ‘Successor’ kingdoms built on his example as a city-founder. His Successors in Asia, the Seleucids, settled dozens of new cities and towns, above all in Syria and Mesopotamia. In Egypt, the Ptolemies added only one city (Ptolemais) but they made his Alexandria the greatest city of the age. In Macedonia and old Greece, the Antigonids also founded yet more cities: the most intriguing is the ‘City of Heaven’ (Uranopolis) which was founded by Antipater’s son Alexarchus, who is said to have compared himself with the sun and sent a letter in a made-up language to his brother Cassander’s new city nearby.

1

Like us, they must have been baffled by it.

Hadrian was residing in just such a great ‘new city’, the Seleucids’ Antioch in Syria, when he heard the news of his accession. Like its founder, Seleucus, he climbed the imposing Jebel-Aqra mountain, the ‘Mount Sion’ of ancient paganism, which towers above it. Although he continued to favour Antioch and gave it funds for a smart new set of baths, he also visited Alexandria in Egypt and enjoyed it much more. He even honoured aspects of this city in the water-garden of his villa in Italy. Like the Successor kings, Hadrian also founded cities in the eastern provinces of his empire. One of them commemorated one of his spectacular hunts; another, ‘Antinoopolis’ in Egypt, commemorated his boyfriend Antinous, who had died nearby while still young.

The continuities here are very strong, for Alexander would have sympathized: he himself founded a city in memory of his dog and would surely have founded such a place for his lover, Hephaestion. Like Hadrian, Alexander and the Successors also founded military colonies in the East. Unlike the Roman colonies of Hadrian’s predecessors, their colonies were not sites for retired soldiers. Instead, their colonies’ land-holding families remained liable to military service. Initially they were not very numerous. The best-known such colony is Dura, on the river Euphrates, for which a maximum population of 6,000 has been proposed at its peak. Recent surveys, however, have shown that its first population was very much smaller.

2

The new cities in Asia were vastly greater places from the start. Alexandria in Egypt soon contained more than 100,000 people and by the second century

BC

it may have risen to more than 300,000. Antioch in north Syria and Seleucia on the Tigris were also enormous. Life in these places was on a different scale to classical Athens, even in the age of Pericles. To put them in context, we can compare the former ‘Great City’, Megalopolis in old Greece which had been founded so triumphantly in the 360s against a weakened Sparta. In 318, just after Alexander’s death, it had only 15,000 men fit for military service, including slaves and foreign residents.

3

The Successor kings’ standing armies were so much bigger, and their numbers were swelled by mercenaries and by colonists on call-up. Armies of 60,000 or more foot soldiers were widely deployed, despite the acute problems of supplies and the transporting of their soldiers’ all-important

personal baggage, often including women. Military life remained at the level exemplified by Alexander. It stayed fairly true to his and Philip’s basic units and formations, but the siege-machinery, fortifications, warships and victory-monuments all grew in size and complexity. The war-elephant, encountered by Alexander, became a regular terror in the Successors’ armies. Above all, the kings in Greece, western Asia and the Levant continued to launch big war-fleets, maintaining their standards of ‘gigantism’ in the Aegean.

With the help of these Alexander-style armies, the Successor kings held down the lands of the old Persian Empire and extracted a high level of tribute. War was essential to a Successor king’s image (ten of the Seleucid kings died on campaign). In turn, it yielded highly valuable booty and was a major element in the kings’ economies, combining with their yearly taxation to support a level of royal luxury far beyond anything which Greeks, even in Sicily, had previously seen. Whereas observers had previously blamed luxury for the fall of this or that city in the eastern or western Greek world, luxury was now used publicly as a statement of royal power. This use is a sign of the end of the fifth and fourth centuries’ classical age.

The Successor kings kept vast war-fleets in their harbours, but in Egypt, the kings themselves had fantastically luxurious boats, real floating palaces which excelled any modern Nile cruiser. They had mines which were worked by slaves, and they themselves enjoyed many of Asia’s new precious stones, on which Theophrastus, Aristotle’s pupil, wrote a work of classification. Macedonian ladies had always liked oils and scents (big pottery jars for them have now been found in their palace-towns), but the Ptolemaic queens encouraged the preparation of new perfumes, for which the court became renowned. The most amazing luxury of all occurred at the celebration of the Ptolemies’ family festival, the Ptolemaia, which King Ptolemy II held in Egypt, probably in winter 275/4.

4

A fantastic procession of wild animals, tableaux, treasure and armed soldiers processed through the streets of Alexandria and then through the city stadium where seated spectators could admire it. The occasion was associated with the gods, especially Dionysus with whom the Ptolemies linked them-selves. It also honoured the dead Ptolemy I, the friend of Alexander, who was now being honoured as a god too. The tableaux included a

huge winepress, worked by men dressed as satyrs, and a personified statue of Mount Nysa, Dionysus’ birthplace, which sat and stood up automatically: there were women dressed as maenads with ivy in their snaky hair. About 25,000 gallons of wine were poured out for the crowds on the streets, while birds, dressed with ribbons, were released for them to catch and take home, no doubt for dinner. A pole, 180 feet high, displayed a gigantic phallus and more than two thousand men tugged floats which included allusions to the Ptolemies’ Greek dependencies abroad and to Alexander in the context of his Indian conquests. A parade of animals included a white bear and a two-horned rhinoceros, all of which were displayed, but not killed. Models of the morning and the evening star evoked the passage of time; 57,000 soldiers marched at the end.

Among his many shows and festivals, not even Alexander had arranged such a spectacle. There were no distinctively Egyptian tableaux, but non-Greeks could join in the occasion because it did not rely on an understanding of Greek. What Egyptians saw was a massive statement of power and splendour, linked to images of Greek gods. Greek visitors from abroad would pick up the allusions to Dionysus’ complex mythology, but everyone, whatever their language, could enjoy the extravagance and the free gifts and engage with the scale of the final march-past. Huge crowns of gold were displayed on several of the floats and were joined by the precious crowns donated by important Greek visitors. These donations went towards the cost of a display which showed off the power and generosity of a ruling family who could afford to make their streets run with milk and wine. Perhaps there were royal festivals of a similar scale in Antioch too, but Alexandria certainly set the standard. Like Alexander, the Ptolemies built the most luxurious dining-rooms and filled them with far more couches and furniture than had ever graced a classical Greek dinner-party. Egypt’s cut flowers were famous all the year round: a single dinner-party in the 250s

BC

was adorned with three hundred wreaths of flowers.

5

King Ptolemy II even decorated the pillared colonnades around his dining-room with paintings which referred to the theatre and to great dinner-parties known in myth.

Alexandria’s golden years were placed by contemporaries in the mid-240s, a period of ‘fair weather’. By then the city had become

extraordinarily impressive. There were straight streets (later said to be up to fifty yards wide) which ran in a rectangular plan, oriented to catch the prevailing wind. The quarters were named after letters of the alphabet (‘B’ and ‘D’ became the main Jewish quarters). The main street ran on past green awnings to no less than three interrelated harbours. The kings had magnificent palaces on the coastline; its erosion later buried their remains under the sea, but they have begun to be revisited by underwater archaeologists. On an islet by the harbour there was an acknowledged ‘wonder of the world’, the gigantic lighthouse, or Pharos. Recent explorations have located its massive blocks on the seabed and proved that two colossal statues of a Ptolemy and his queen in the style of Egypt’s Pharaohs stood at the base of the monument. Throughout the city, such bits of ancient Egyptian statuary were re-erected as decoration. The lighthouse was dedicated not by a Ptolemy but by an immigrant Greek courtier, Sostratos, who was rich enough to pay for it. Stories were told of the fire-beacon which blazed on top of it and even of the mirror which reflected its light, but nobody has yet reconstructed the upper levels definitively.

This wonder of a lighthouse was obviously very necessary: shipwrecks have been located on the nearby seabed. The royal palaces housed two less mundane marvels: a ‘Museum’ and a huge library. The Greek tyrants of the past had competed for artists and poets, and one of them, Polycrates of Samos, was credited with a special library of books. In Alexandria, these ideas were encouraged by intellectual fashion, especially by Demetrius the Athenian, the immigrant follower of Aristotle; Aristotle himself had had a grand library and had founded a religious society for his pupils’ studies. These Aristotelian examples now found a new grand patron. The Ptolemies used libraries to amass all the Greek texts in existence. They forced visitors who arrived with scrolls to surrender them for copying and they even kidnapped the Athenians’ master-copies of their great tragedies. The biggest library, located in their palace, was said to have grown to nearly 500,000 volumes. Scholars gave it a catalogue, and although the texts were not for public consultation, a second library, in the temple of the god Serapis, was smaller and perhaps more accessible.

Old and new Greek texts made Alexandria, the city of so many disparate Greeks, into the powerhouse of all Greek culture. Like the

royal processions, the texts enhanced the kings’ power and prestige. The rival great cities, therefore, joined in the library race. There was a major library in the Seleucids’ capital, Antioch. Recently, a fragment of a philosophy dialogue, based on Plato, was discovered on parchment in the remains of the Greek city at Ai Khanum, up by the river Oxus in modern Afghanistan; the room which contained it may perhaps have been a palace library too.

6

In the second century

BC

the rival kings at Pergamum, in western Asia, founded a major library of their own. The Pergamene kings competed with the Ptolemies and when their rivals tried to deny them Egyptian papyrus for their texts, they took to using parchment, made from animal skins, instead. Ultimately, Hadrian was heir to this Hellenistic habit. He was a great donor of libraries, not least to Athens where his library’s grand plan is still visible.

Demand, inevitably, encouraged fakes, like the faking of several ‘antiquities’ for the huge buying power of today’s Getty Museum in America. In Alexandria, the kings also maintained a building whose contents were the real thing, a scholarly ‘society of the Muses’, the world’s first Museum. Its assets were humans, not antiques. Important Greek scholars were attracted by the pay, the offer of free meals and access to the nearby library. In due course, they edited and tidied up the texts of the Greek classics, including Homer’s epics. They included some lively and erudite poets, the immensely learned Eratosthenes who calculated the circumference of the earth, almost correctly, and the mathematical genius Euclid. Euclid’s famous book of

Elements

set out definitions, mostly Euclid’s own, ‘postulates’ and axioms and proved them by penetrating arguments which built on each other, stage by stage. They are still admired for their method. Unfortunately, less is known of Aristarchus, an astronomer from Samos. His work on the ‘size and distance of the sun and moon’ survives, but his greatest claim to fame is his theory that the sun is the centre of the universe and the earth goes round it in circular motion. This brilliant new idea became controversial, but it was perhaps only aired as a possibility, not as an ‘axiom’ admitting of proof. In the early to mid-third century

BC

such men justify Alexandrias’ reputation as a centre of scholarship and science.

In the third century

BC

Greek medicine also made its greatest

progress, owing it to two Greek immigrants in the kings’ big cities. In Antioch, Erasistratus examined the valves of the heart and theorized that ‘breath’ passed through the arteries. In Alexandria, Herophilus made amazing progress in discovering the nerves, ventricles in the brain, ovaries (though he did not understand their purpose) and much else, while writing admirably about the pulse. The Ptolemies are said to have helped this great leap of knowledge by making condemned prisoners available not just for dissection but for vivisection too. The doctors’ brief access to living anatomy bore a cruel, but valuable, fruit. Egyptian medicine, by contrast, had tended to trace all diseases to that root of evil, the backside.