The Classical World (5 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

In my view,

poleis

‘rose’ at different times in different parts of

Greece, but they certainly arose before the 730s

BC

and are most likely to have formed

c.

900–750

BC

. By the time of Hadrian, a thousand years later, ‘city-states’ of the

polis

type have been estimated to have contained about 30 million people, about half of the estimated population of the Roman Empire. The combination of a main town, a country-territory and villages remained typical, although the political rights of these elements varied over time and place. If Hadrian had ever counted, he would probably have reckoned up about 1,500

poleis

, of which about half were in what is now Greece and Cyprus and on the western coast of Asia Minor (now Turkey). These 750 or so were mostly city-states of the Greeks’ earlier classical age. The others had been settled in lands ranging from Spain as far (with Alexander) as north-west India.

During the ninth and eighth centuries

BC

Greeks in Greece and the Aegean islands settled many more villages in the territories of what were increasingly identifiable

poleis

. This process was one of local settlement, not long-range migration. Then several of these

polis

centres began, from

c.

750

BC

onwards, to send settlers to yet more

poleis

overseas. Settlement overseas was an enduring aspect of Greek civilization: by Hadrian’s time, as now, more Greeks lived outside poor, sparse Greece than lived in it. In the age of the Mycenaean palaces, too, Greeks had already travelled to Sicily, south Italy, Egypt and the coast of Asia, settling even on the site of Miletus.

2

Afterwards,

c.

1170

BC

, emigrants from the ending of the palace-states had gone east and settled especially on Cyprus. Later, perhaps

c.

1100–950

BC

, yet more migrants from the eastern coastline of Greece had crossed the Aegean, stopped on some of the intervening islands and then settled on the western coast of Asia Minor. These east Greeks had become resident on sites which would later be world-famous

poleis

, such as Ephesus or Miletus. Archaeology shows that one such site, Smyrna, had walls and the signs of being a

polis

, in my view, by

c.

800

BC

.

The ‘Greek world’, therefore, had been changing in scope quite considerably, even before Homer’s lifetime. In the eighth century

BC

there was no country simply called ‘Greece’, let alone one with Greece’s modern national boundaries: in Homer, the modern name of Greece, ‘Hellas’, refers only to one area of Thessaly. However,

there was a common widely spoken Greek language which divided into only a few dialects (three are the most significant: Aeolic, Ionic and Doric): communication between differing Greek dialect-speakers was not a significant problem. Underlying each Greek

polis

there were also similar groupings, the

phulai

, which we misleadingly translate as ‘tribes’. Again, their uniformity is more striking than their diversity: three particular ‘tribes’ existed in Doric Greek communities, four particular ones in Ionian ones. When Greeks emigrated across to settle on the coast of Asia from

c

. 1100

BC

onwards it is striking that they took the precise dialect of Greek which prevailed in their former area of ‘Greece’ and also replicated the same ‘tribes’. Modern scholars, among the ethnic confusions of our age, like to pose the question of whether a ‘Greek identity’ existed, and if so, when. Back in the ‘dark ages’ before Homer, Greeks did share similar gods and goddesses and speak a broadly similar language. Faced with our modern post-nationalist question, ‘Are you Greek?’, they might have hesitated, because they had probably never formulated it in such sharp terms. But fundamentally, they would say that they were, because they were aware of such common cultural features as their language and religion. Back in the Mycenaean age, eastern kingdoms did already write about ‘Ahhijawa’ from across the seas, surely the ‘Achaeans’ of a Greek world.

3

In Homer’s epic, they are already ‘Pan-Achaeans’; ‘Greekness’ is not a late, post-Homeric invention.

Between

c.

900 and 780

BC

, however, actual settlement by Greeks overseas is no longer evident to us. What continued was travel by Greeks, exactly what Homer describes for his hero Odysseus and his companions. In their case, they are travelling home by sea from Troy, but it is striking that they never try to establish a settlement on their way (though many Greek

poleis

in the West later claimed, quite wrongly, to be the site of one or other ‘fairytale’ place on their journey). Odysseus’ voyage was ‘pre-colonial’. Thanks to archaeology, we now know more about the real ‘pre-colonial’ travellers who moved around in and before Homer’s lifetime. They came especially from Greek islands in the east Aegean which were temptingly close to the more civilized kingdoms of the Near East. In the ninth and eighth centuries

BC

, Crete, Rhodes and the Greek settlements on Cyprus were important starting points, but, to judge from the Greek pottery

which accompanied these travellers, the most prominent were settlements on the island of Euboea, just off the eastern coast of Greece. The range of these Euboeans’ Asian travels was forgotten by the Greeks’ own later historians, and archaeologists have only recovered much of it by brilliant studies in the past forty-five years. We can now trace these Euboeans to stopping-off points along the coast of Cyprus and on the coast of the Levant, including the great city of Tyre (already by

c.

920

BC

): a Euboean cup has even been found in Israel, near the Sea of Galilee, in a context which probably dates to

c.

900

BC

.

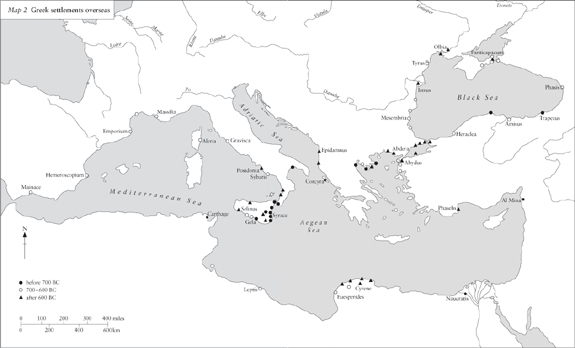

These travels led on, once again, to actual settlements. By

c.

780

BC

, we can trace Euboean Greeks among the first occupants of a small seaside settlement, Al Mina in north Syria. Soon afterwards, Euboeans turn up at the other end of the Greek Mediterranean, as visitors to the east coast of Sicily and as settlers on the island of Ischia, just beyond the Bay of Naples. On Ischia, highly skilled excavation has made their settlement a focal point of modern study, but arguably, it was preceded by Euboean staging-posts on the Straits of Otranto between south-east Italy and modern Albania. Euboeans also settled on the coast of north Africa, as ancient place-names for some of the islands off modern Tunisia attest for us. Metals, especially the copper and tin which make bronze, were one magnet for these Euboean Greeks’ travels both to the East and the West. In return, they brought their decorated pottery (cups, jars and plates, though not, on present evidence, any plates to the West). Perhaps they also made a profit by carrying goods from other less enterprising Greek settlements. They may also have brought wine with them, perhaps transporting it in skins. Certainly, in the fifth century

BC

Greek wine was imported in quantity into the Levant: in the nineteenth century

AD

Greek wine from Euboea, from the town of Koumi (ancient Cumae), was imported in vast quantities into Istanbul.

Sicily, Libya, Cyprus and the Levant were all points of Euboean contact before

c.

750

BC

, and all of them are famous points of contact for heroes who are travelling in Homer’s epics. On their way west, Euboeans and other Greeks also stopped on the island of Ithaca, home of Homer’s Odysseus. The Greeks’ travels of the ninth to mid-eighth centuries were important, then, for some of the travel-details which Homeric poetry includes. Euboea itself was the scene for another great

poetic event,

c.

710

BC

: the victory of the poet Hesiod (in most scholars’ view, a younger poet than Homer) with a prize-poem which was probably his

Theogony

or Birth of the Gods. Appropriately for its prize-giving audience, this poem had much to say about legends which Euboeans would have picked up on their travels from peoples they met in the East. For Greeks were not travelling into empty lands in the lifetimes of Homer and Hesiod, nor were they the only travellers on the seas. Levantine people whom Greeks called ‘Phoenicians’ (‘purple people’, from their skill with a purple dye) were also crisscrossing the Mediterranean. By

c.

750–720

BC

these Phoenicians had gone as far west as the southern coast of Spain and even out beyond the straits of Gibraltar. Precious metals attracted them here too, especially the silver which was mined in the far West. The Phoenicians’ example may even have spurred on Greeks to renewed settlement abroad, rather than just to travelling to and fro. In the mid- to late ninth century

BC

‘Phoenicians’ from Tyre and Sidon had already settled two ‘new towns’ abroad, places which they called ‘Qart Hadasht’. One was at the modern Larnaca beside its salt lake on the coast of Cyprus; the other ‘Qart Hadasht’ (which we call ‘Carthage’) was on Cape Bon in modern Tunisia.

Sixty years or so after the settlement of these Phoenician ‘new towns’, Greeks then settled on the western island of Ischia, where Levantines were also present; from there, Greek settlers moved across to the Italian coast opposite and founded Cumae, giving it a name for a

polis

already known on Euboea. From the mid-730s a spate of Greek settlements then began on the fertile eastern coast of Sicily: it marked a clear, new phase in expatriate Greek history. Meanwhile, the more distant western Mediterranean, including Spain and north Africa, was being settled by Phoenicians: there was probably a developing rivalry between Phoenicians and Greeks and by the sixth century

BC

, certainly, the western Mediterranean was to be kept ever more jealously as the particular sphere of Phoenicians, especially those who were settled at Carthage. Instead, Greeks settled on the south Italian coast and on the coastline of modern Albania. Back in their own Aegean orbit, they continued to settle on northern shores, on the Macedonian coast and in the Chalcidic peninsula (one of whose prongs is Mount Athos). They also travelled up into the inhospitable

Black Sea, some of whose rivers were already known to Hesiod: in due course, these contacts grew into

poleis

too, probably at first on its southern coast, then up on the northern one too. North Africa and Egypt also attracted renewed Greek interest. By

c.

630

BC

, a small party of Greeks had established themselves in Libya at the wonderfully fertile site of Cyrene. In Egypt, others had already started to settle on the western arm of the Nile Delta. Within two centuries the Greek map had been transformed, especially when the first Greek settlements in a region went on to found secondary settlements there too. By 550

BC

, more than sixty major Greek settlements overseas can be counted, from south-east Spain to the Crimea, almost all of which were to endure as

poleis

for centuries.

Nobody was writing a memoir or history in these years and so a study of the reasons for these settlements has to turn to much later written sources which tend to add elements of folktale and legend. Too often, they cited ‘drought’, a sign of divine anger, as the cause of emigration. There were also stories of chance adventures, divine intervention or even invitations to Greeks from local rulers. In more general terms, we can presume that reports of good land and easily conquerable neighbours had come back with the earlier Greek raiders and traders who had been touching on Sicily, Italy or the southern coast of the Black Sea since

c.

770–740

BC

. Back at home, their Greek communities were dominated by small aristocracies who controlled most of the land and benefited from it; indeed they needed it, if they were to graze so many of their all-important horses. In the more outward-looking Greek communities, there was probably also a rise in the population in the mid- to late eighth century. The rise need not have vastly increased the total numbers: as always, Greek families would expect many children to die (half or more of all births, on most modern estimates), whilst the surplus survivors could be exposed in most communities. At best, the exposed ones might be taken and brought up elsewhere as slaves. But there would certainly be an unequal distribution of surviving children between individual families. Less-fertile families could procure a son and heir by adoption, but even so, fertile families might still have a son or two to spare. They would not grow up to be wandering dispossessed sons: Greek families always split their inheritances formally between their sons, but the

male heirs were capable of surviving informally on a family property by agreeing to share into the next generation. But a better opportunity elsewhere would certainly seem attractive to brothers in such families. There would also, as always, be a few unpopular boys among the aristocrats and a few potential troublemakers in the lower classes. When news arrived of good land abroad, it was attractive for the ruling class to choose a noble leader, collect or conscript some unwanted settlers and send them away to try their luck. We hear very occasionally of an enterprising priestess who left to help with an overseas settlement, but probably Greek women were usually left behind. In Libya and up on the Black Sea coast, it was remembered how the first Greek settlers took local women. Here, and no doubt elsewhere, the future citizens of the Greek settlements had a very mixed ethnic beginning.