The Code Book (17 page)

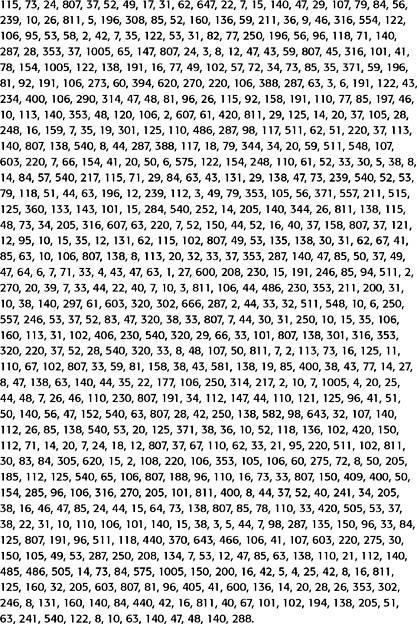

Figure 21

The first Beale cipher.

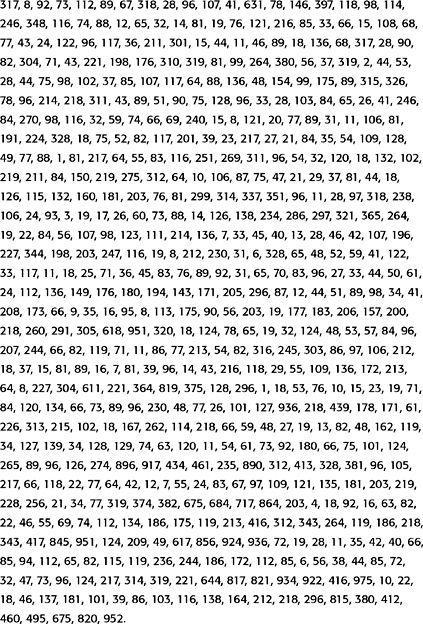

Figure 22

The second Beale cipher.

Figure 23

The third Beale cipher.

First, the cryptographer sequentially numbers every word in the keytext. Thereafter, each number acts as a substitute for the initial letter of its associated word.

1

For

2

example,

3

if

4

the

5

sender

6

and

7

receiver

8

agreed

9

that

10

this

11

sentence

12

were

13

to

14

be

15

the

16

keytext,

17

then

18

every

19

word

20

would

21

be

22

numerically

23

labeled,

24

each

25

number

26

providing

27

the

28

basis

29

for

30

encryption. Next, a list would be drawn up matching each number to the initial letter of its associated word:

1 = f

2 = e

3 = i

4 = t

5 = s

6 = a

7 = r

8 = a

9 = t

10 = t

11 = s

12 = w

13 = t

14 = b

15 = t

16 = k

17 = t

18 = e

19 = w

20 = w

21 = b

22 = n

23 = l

24 = e

25 = n

26 = p

27 = t

28 = b

29 = f

30 = e

A message can now be encrypted by substituting letters in the plaintext for numbers according to the list. In this list, the plaintext letter f would be substituted with 1, and the plaintext letter e could be substituted with either 2, 18, 24 or 30. Because our keytext is such a short sentence, we do not have numbers that could replace rare letters such as x and z, but we do have enough substitutes to encipher the word beale, which could be 14-2-8-23-18. If the intended receiver has a copy of the keytext, then deciphering the encrypted message is trivial. However, if a third party intercepts only the ciphertext, then cryptanalysis depends on somehow identifying the keytext. The author of the pamphlet wrote, “With this idea, a test was made of every book I could procure, by numbering its letters and comparing the numbers with those of the manuscript; all to no purpose, however, until the Declaration of Independence afforded the clue to one of the papers, and revived all my hopes.”

The Declaration of Independence turned out to be the keytext for the second Beale cipher, and by numbering the words in the Declaration it is possible to unravel it.

Figure 24

shows the start of the Declaration of Independence, with every tenth word numbered to help the reader see how the decipherment works.

Figure 22

shows the ciphertext-the first number is 115, and the 115th word in the Declaration is “instituted,” so the first number represents i. The second number in the ciphertext is 73, and the 73rd word in the Declaration is “hold,” so the second number represents h. Here is the whole decipherment, as printed in the pamphlet:

I have deposited in the county of Bedford, about four miles from Buford’s, in an excavation or vault, six feet below the surface of the ground, the following articles, belonging jointly to the parties whose names are given in number “3,” herewith:

The first deposit consisted of one thousand and fourteen pounds of gold, and three thousand eight hundred and twelve pounds of silver, deposited November, 1819. The second was made December, 1821, and consisted of nineteen hundred and seven pounds of gold, and twelve hundred and eighty-eight pounds of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange for silver to save transportation, and valued at $13,000.

The above is securely packed in iron pots, with iron covers. The vault is roughly lined with stone, and the vessels rest on solid stone, and are covered with others. Paper number “1” describes the exact locality of the vault, so that no difficulty will be had in finding it.

It is worth noting that there are some errors in the ciphertext. For example, the decipherment includes the words “four miles,” which relies on the 95th word of the Declaration of Independence beginning with the letter

u

. However, the 95th word is “

in

alienable.” This could be the result of Beale’s sloppy encryption, or it could be that Beale had a copy of the Declaration in which the 95th word was “

un

alienable,” which does appear in some versions dating from the early nineteenth century. Either way, the successful decipherment clearly indicated the value of the treasure-at least $20 million at today’s bullion prices.

Not surprisingly, once the author knew the value of the treasure, he spent increasing amounts of time analyzing the other two cipher sheets, particularly the first Beale cipher, which describes the treasure’s location. Despite strenuous efforts he failed, and the ciphers brought him nothing but sorrow:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes

10

necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which

20

have connected them with another, and to assume among the

30

powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to

40

which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle

50

them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires

60

that they should declare the causes which impel them to

70

the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident,

80

that all men are created equal, that they are endowed

90

by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these

100

are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; That to

110

secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their

120

just powers from the consent of the governed; That whenever

130

any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it

140

is the right of the people to alter or to

150

abolish it, and to institute a new government, laying its

160

foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such

170

form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect

180

their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments

190

long established should not be changed for light and transient

200

causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are

210

more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to

220

right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are

230

accustomed.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations,

240

pursuing invariably the same object evinces a design to reduce them

250

under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their

260

duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new

270

Guards for their future security. Such has been the patient

280

sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity

290

which constrains them to alter their former systems of government.

300

The history of the present King of Great Britain is

310

a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in

320

direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these

330

States. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a

340

candid world.

Figure 24

The first three paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence, with every tenth word numbered. This is the key for deciphering the second Beale cipher.

In consequence of the time lost in the above investigation, I have been reduced from comparative affluence to absolute penury, entailing suffering upon those it was my duty to protect, and this, too, in spite of their remonstrations. My eyes were at last opened to their condition, and I resolved to sever at once, and forever, all connection with the affair, and retrieve, if possible, my errors. To do this, as the best means of placing temptation beyond my reach, I determined to make public the whole matter, and shift from my shoulders my responsibility to Mr. Morriss.

Thus the ciphers, along with everything else known by the author, were published in 1885. Although a warehouse fire destroyed most of the pamphlets, those that survived caused quite a stir in Lynchburg. Among the most ardent treasure hunters attracted to the Beale ciphers were the Hart brothers, George and Clayton. For years they pored over the two remaining ciphers, mounting various forms of cryptanalytic attack, occasionally fooling themselves into believing that they had a solution. A false line of attack will sometimes generate a few tantalizing words within a sea of gibberish, which then encourages the cryptanalyst to devise a series of caveats to excuse the gibberish. To an unbiased observer the decipherment is clearly nothing more than wishful thinking, but to the blinkered treasure hunter it makes complete sense. One of the Harts’ tentative decipherments encouraged them to use dynamite to excavate a particular site; unfortunately, the resulting crater yielded no gold. Although Clayton Hart gave up in 1912, George continued working on the Beale ciphers until 1952. An even more persistent Beale fanatic has been Hiram Herbert, Jr., who first became interested in 1923 and whose obsession continued right through to the 1970s. He, too, had nothing to show for his efforts.

Professional cryptanalysts have also embarked on the Beale treasure trail. Herbert O. Yardley, who founded the U.S. Cipher Bureau (known as the American Black Chamber) at the end of the First World War, was intrigued by the Beale ciphers, as was Colonel William Friedman, the dominant figure in American cryptanalysis during the first half of the twentieth century. While he was in charge of the Signal Intelligence Service, he made the Beale ciphers part of the training program, presumably because, as his wife once said, he believed the ciphers to be of “diabolical ingenuity, specifically designed to lure the unwary reader.” The Friedman archive, established after his death in 1969 at the George C. Marshall Research Center, is frequently consulted by military historians, but the great majority of visitors are eager Beale devotees, hoping to follow up some of the great man’s leads. More recently, one of the major figures in the hunt for the Beale treasure has been Carl Hammer, retired director of computer science at Sperry Univac and one of the pioneers of computer cryptanalysis. According to Hammer, “the Beale ciphers have occupied at least 10% of the best cryptanalytic minds in the country. And not a dime of this effort should be begrudged. The work—even the lines that have led into blind alleys—has more than paid for itself in advancing and refining computer research.” Hammer has been a prominent member of the Beale Cypher and Treasure Association, founded in the 1960s to encourage interest in the Beale mystery. Initially, the Association required that any member who discovered the treasure should share it with the other members, but this obligation seemed to deter many Beale prospectors from joining, and so the Association soon dropped the condition.